Marginalia of Rudolf Steiner’s Life and Work, No. 23 – In peripheral encounters, and once directly, Ludwig Berger circled around Rudolf Steiner. Above all, his Bible commentaries developed with Emil Bock were a gateway to spiritual science for Berger.

Ludwig Berger (originally: Bamberger) was born on January 6, 1892, into a musical family in Mainz. His mother, Anna Klara, was a pianist, and his father, Franz, was a banker by profession, but his whole heart belonged to music. He determined which instruments his three sons had to learn to create a quartet in the family. Ludwig was assigned the cello.

During these nights, Rudolf Steiner opened up the Bible to me anew.

In 1910 he began studying art history, German, and literature in Munich. In 1911 he attended a performance of Wedekind’s ‹King Nicolo› and experienced something peculiar: «In the foyer of the Schauspielhaus, during the intermission […], I met a face that seemed to consist only of an eye. – Immediately impressed by the play, two youths, my friend Hans Carl […] and I, were strolling when suddenly a glance met me. I waited until we were at the other end of the corridor before I dared to ask Hans: ‹Who was that?› ‹Rudolf Steiner!› He said nothing more, and I asked nothing more. Were there still names with magic? I felt very clearly; this look had asked me something that worried me.» (p. 54)1

Shortly afterward, two acquaintances from the Munich guesthouse where Ludwig Berger had his room went to a lecture and considered taking him with them but decided against it. «I asked the next day where they had been yesterday. ‹At Rudolf Steiner […] ›» From the strange fragments that Berger heard from the lecture, he could not put anything together and remained silent «out of ignorance.» Looking back, he noted: «At that time, I haunted this great admonisher, who walked like a Rosicrucian through the darkness of time. But with such a generous letter of credit as my father gave me, who would ever have thought of looking for that tiny bottleneck that makes distress visible to the eye?» (p. 55)

Berger moved to Heidelberg for further studies and made the better acquaintance of Max Weber, who impressed him deeply. One day, a quartet partner took him to play music at the nearby Neuburg Abbey – to Alexander von Bernus. He was admonished that there was a lady in mourning who should not be addressed – he learned that it was Marie von Sivers.2

In 1914 Ludwig Berger received his doctorate with a thesis on the painter Seekatz. However, he came to the theater via strange detours and was allowed to stage Mozart’s ‹Gardener for Love› at the Stadttheater Mainz in 1916. The autodidact was so successful that he received further commissions and initially went to Hamburg.

Friedrich Kayßler, Christian Morgenstern’s lifetime friend, then called him to Berlin. «He gave me poems by Morgenstern to read. I thought they were beautiful. ‹Nothing more?› Kayßler looked me inquiringly in the face.» (p. 105) But at the time, Berger was overflowing with Shakespeare, whose ‹Measure for Measure› he was currently translating anew. There was an estrangement from Kayßler, and Berger went to Max Reinhardt, who gave him a contract with fabulous conditions. After a few productions there, he was finally asked if he wanted to make a movie. He made his debut in 1920 – so successful that he was able to shoot a top-class cast and successful movies in the following years. His brother Rudolf, who was four years older, realized the movie buildings as an architect (he was deported to Auschwitz in 1944 and died there shortly before liberation under unexplained circumstances). One day in 1922, during this time in Berlin, a friend stormed into the room and excitedly reported that Friedrich Rittelmeyer had bid ‹farewell› to his Berlin congregation today because he confessed to Rudolf Steiner’s «spiritual science, which reinterpreted the Bible text and explained it in close connection with the ancient world of mysteries.» The friend had such a strong effect «that we left the work behind. Theatre was a fascinating profession that made us forget the world around us, but it also frightened me that we failed to witness new spiritual movements.» (p. 143 f.)

Bible in Nights of Bombing

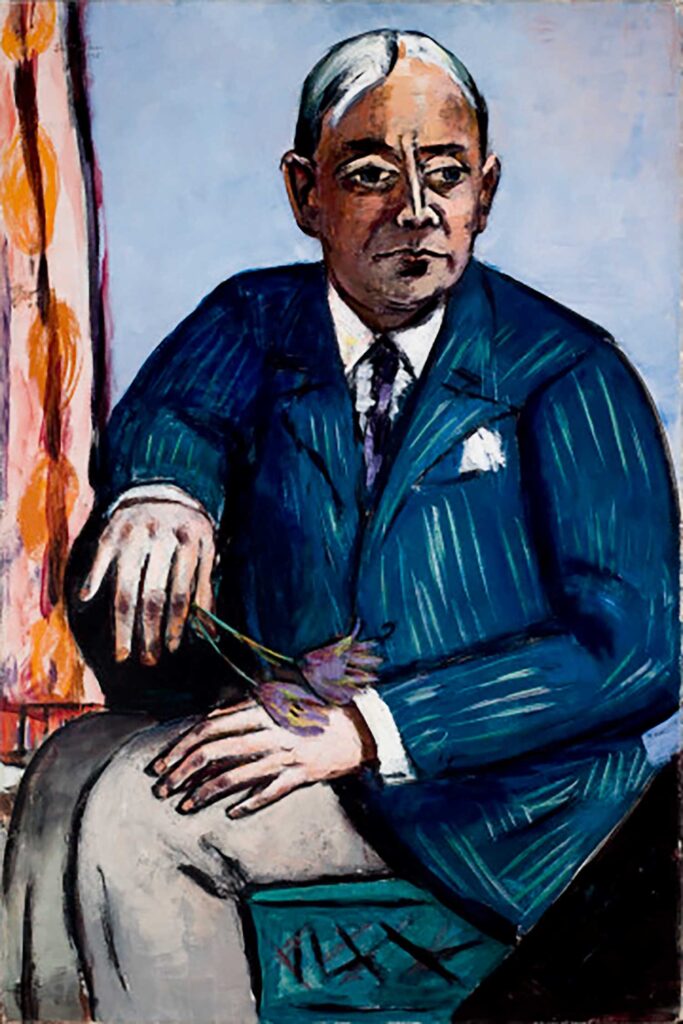

Soon Hollywood became aware of Berger, and he made several movies for Paramount, among others, with Pola Negri and Gary Cooper. Back in Germany, he made some of his best-known movies, including ‹Der Walzerkrieg› with Renate Müller and Willy Fritsch in 1933. But with the seizure of power by the National Socialists, he had to emigrate, as a Jew. After staying in the Netherlands, France, and Great Britain, where he was also able to shoot movies, again and again, he settled in Amsterdam with his blind mother in 1938. There he met the painter Max Beckmann, who painted a portrait of him.

When Amsterdam was already being bombed, a lodger in the house gave him «books to read that made the nights of the bombing of war real times of treasure hunting,» as they solved many riddles of his childhood: «I was almost happy when the thunder began in the dark. Then there was little danger that one fell asleep and one gained precious hours for knowledge. Everything that had pushed and hurt me as a child in religious education was now transfigured into crystalline clarity as the spotlights swept past outside […].» (p. 363)

It was Emil Bock’s ‹Contributions to the Intellectual History of Mankind› that he read: «Behind the name, Emil Bock rose the other, important, first: Rudolf Steiner. […] During these nights, Rudolf Steiner opened up the Bible to me anew.» (p. 365)

Later, after the war, there was a long-standing correspondence between Ludwig Berger and Emil Bock.3, they also met a few times in person. Berger worked in Germany again from 1947 as a theatre, movie, and radio play director and was one of the pioneers of German television. Occasionally he played in movies in minor roles himself. But he was also active as a writer and headed the performing arts department at the Academy of Arts in West Berlin. He has received numerous awards for his work.

Through Ludwig Berger, Franz Werfel’s close friend, the publicist Willy Haas (1891–1973) at least came close to Anthroposophy. As a teenager, Haas had met Rudolf Steiner through his revered aunt Hedwig Bergmann in Berlin.4 When he later discussed this with Berger, he did not hide the «catastrophic impression» that Rudolf Steiner’s person, «his spoken word and later also his poetry had made on me. Ludwig Berger admitted Steiner’s sometimes unfavorable personal appearance. He advised me not to read the esoteric writings at all for the time being but for the time being to read the Bible commentaries of his most trusted and wise follower, Liz. Emil Bock. Berger also gave me three volumes, and I read these witty Bible interpretations with a burning interest. This way, Caliban 5 can perhaps say that he finally found his way close to Steiner, albeit not quite to him.»6

Image Ludwig Berger with Emil Jannings in the film ‹The Sins of the Fathers› (from: Mein Film, issue 152/1928, p. 4.) – Translation: Monika Werner

Footnotes

- Unless otherwise stated, all quotations are from Ludwig Berger’s autobiography, ‹We Are Made of the Same Stuff Dreams Are Made Of. Sum of a Life›. Tübingen 1953.

- Berger writes that she was mourning for her sister, but in 1912, she was probably more grieving for her mother, who had died in the summer of 1912.

- See Emil Bock, Letters. Stuttgart 1968, p. 360–374.

- In 1925, when Haas founded his journal ‹Die Literarische Welt› together with Ernst Rowohlt, he wrote to Rudolf Steiner on March 26 and asked him «devotedly» for his cooperation: «I do not have to tell you expressly how important it is to me, especially in a revue that will strive to bring together the liveliest and deepest minds of Germany […] To unite, among the first to let you come to your word. It would be best if this did not happen by chance and sporadically, but if you could decide to tell us constantly about the most important journalistic events in Anthroposophical literature; however, it is far from me to impose any material or aesthetic restriction on you, I would kindly ask you to do so in the most popular form possible since our Review, which appears in newspaper format and a considerable circulation, aims to bring the most important intellectual problems and personalities of the time to a large audience. – It would be no less important to me to receive constant reports about Dr. Steiner’s eurhythmy.» (RSA)

- Willy Haas’ journalistic pseudonym after the Shakespeare character from ‹The Tempest›.

- Quoted from Wolfgang Vögele (ed.), The Other Rudolf Steiner. Dornach 2005, p. 179.