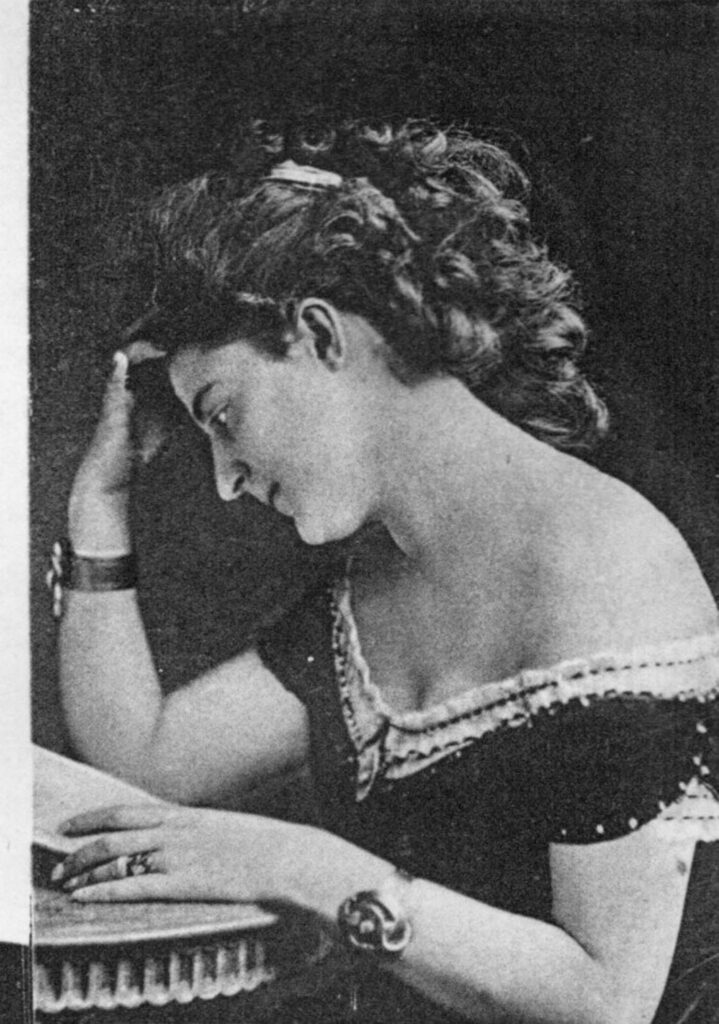

The life of Helene von Schewitsch was so incredibly dramatic, so full of twists and turns, and populated with so many of her famous contemporaries that if this extraordinary woman’s biography were a novel, much of it would be considered a complete exaggeration.

Alfred Meebold described “her indomitable temperament, her perpetually lively intellect, . . . her empathy, which was instantly implemented as either sympathy or antipathy, her lively imagination . . . . All this contained, as I understand it, an enormously strong urge for freedom. It was at work in a female body and in one of unusual beauty . . . .”1

Helene von Schewitsch née Helene von Dönniges, was born in Berlin on March 21, 1843. She was the eldest of diplomat Wilhelm von Dönniges and his wife Franziska Wolff’s seven children. Her younger sister Margarethe was to become the mother of Karl von Keyserlingk, on whose Koberwitz estate the agricultural course was held in 1924.2 The Bavarian king had taken her father into his service, so Helene spent her early childhood in Munich. Her parents ran a large salon there, whose relaxed atmosphere characterised her upbringing. For a time, Ludwig II of Bavaria, two years her junior, was her playmate—that is, until her father ended the children’s play together, following an argument between them, with the words: “One does not thrash one’s future king!”3

Helene’s relationship with her mother became difficult when her mother engaged the twelve-year-old to an Italian colonel thirty years her senior. A few years later (while living with her family in Nice from 1859 to 1861), Helene broke off the engagement. She then enjoyed the easy life on the French Riviera as a celebrated beauty and queen of the balls, until the time when she was sent to live with her beloved grandmother in Berlin. There, she met the Romanian prince and law student Janco von Racowitza (1843–1865), whom she had known before and who was entirely devoted to her. She, however, harboured more sibling-like feelings for him.

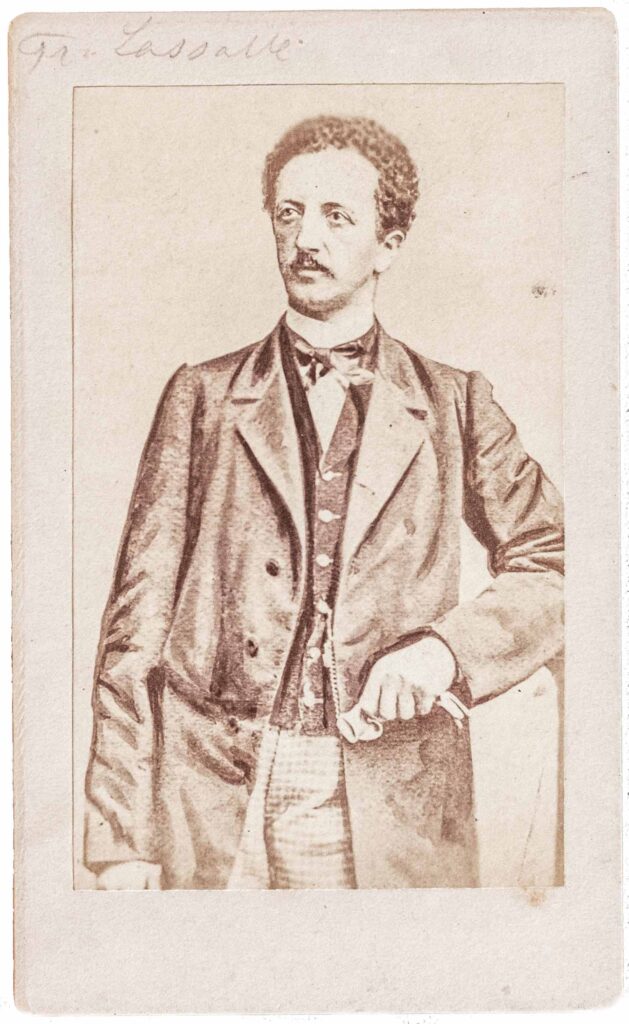

Ferdinand Lassalle

After being told by two different parties that she was the right woman for the famous writer, socialist politician, and notorious playboy Ferdinand Lassalle (1825–1864), she was eager to get to know him. When the two finally met in a societal gathering, Lassalle told her, when saying in his farewell, “Tomorrow I’ll pay your grandmother a visit and fetch the word of consent.” But Helene anxiously warded him off. Their subsequent encounters in Berlin were intense but remained noncommittal, probably because Lassalle was extraordinarily busy with all the other pursuits of his heart. It was only when the two met again by chance on Mount Rigi in Switzerland in July 1864 (Lassalle was recuperating there, and Helene was on an excursion with friends) that their love inflamed in full force. Lassalle followed her to Bern, where they spent a few happy days together. She rejected his proposal to get married on the spot in France, as she wanted her parents’ consent. So, she travelled to Geneva to meet them; Lassalle was to follow shortly.

What happened next—an incredible chain of unfortunate circumstances that fill entire books—we can only hint at here. Her parents were absolutely opposed to her union with the “revolutionary.” Her father placed Helene under confinement. At times, she was accompanied at night by Eugen von Keyserling, her sister’s fiancé, and taken across Lake Geneva to another location. Ultimately, her father forced his daughter, who was actually of age but (as Lassalle had recognised early on) was weak-willed, to write a farewell letter to him. As Lassalle’s letters show, this resistance initially made his love even more ardent. He went as far as to approach Richard Wagner and the Bavarian king, and even (as a Jew) wanted to be baptised by Bishop Ketteler. At the same time, however, it can be learned from his letters that Lassalle (deeply affronted by Helene’s father), at a certain point, believed that he owed it to his own self-esteem not to yield. This ultimately led to a demand for a duel with Helene’s father. In the meantime, however, Wilhelm von Dönniges had sent for Janko von Racowitza, who was inexperienced in matters of arms (and, at the time, was still considered Helene’s fiancé) and bid him to take on the good pistol shooter Lassalle in his place. And yet, the unexpected happened: Racowitza injured Lassalle so badly (accidentally, as Helene von Schewitsch describes it) that he died three days later, on August 31, 1864.

In 1898, Rudolf Steiner wrote about the death of Lassalle, who was a controversial but highly respected interlocutor for Bismarck, and what it meant for the development of Germany: “I believe there would have been a possibility for Bismarck to actualize his social kingdom.4 This possibility would have come to pass if Lassalle had not lost his life in 1864 as a result of Racowitza’s frivolous pistol shot. Bismarck could not deal with principles and ideas. They lay outside the circle of his worldview. He could only negotiate with human beings who replied with real facts. Had Lassalle remained alive, he would probably have brought the workers to the point where they could have found a solution to the social question for Germany in agreement with Bismarck by the time Bismarck was ripe for plans for social reform. At the moment Bismarck needed to solve the social question, Lassalle was missing. . . . If Lassalle had confronted him as a power factor, with the workers as this power, then Bismarck could have founded the social state with the king at its head.”5 It is also clear from other mentions of Lassalle that Rudolf Steiner respected him very much: “I know of no human being who was a greater thinker than Lassalle. He was only very one-sided.”6

Lassalle wrote to Helene on August 20, 1864, in his reply to her farewell letter: “But, if you shatter me through this roguish betrayal, which I cannot overcome, may my fate fall back on you and my curse follow you to the grave! It is the curse of the most faithful heart, deceitfully broken by you, with which you played the most shameful game.” When we look at the further course of her life, we may very well ask ourselves: Did this curse work?

Meeting with Blavatsky

After Lassalle’s death, Helene von Dönniges met with hostility from many sides, especially when, after a short time, she married Janko von Racowitza. But, he died of a lung disease after a few months. Helene broke with her family and was thereby left completely penniless and forced to work. She trained as an actress—her speciality was the “salonnière”—and, in 1868, married her teacher, the character actor Siegwart Friedmann (1842–1916). The marriage ended in divorce in 1873, but the two remained good friends.

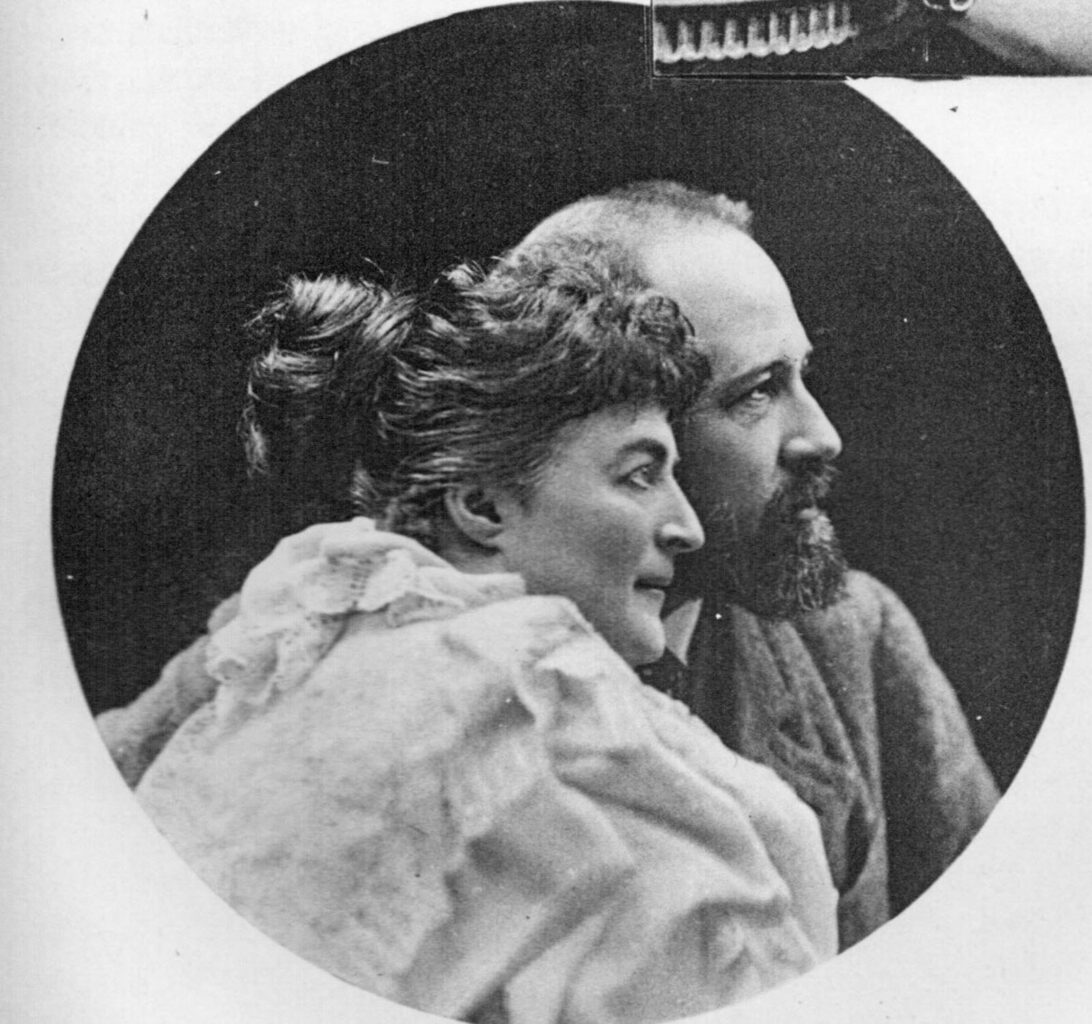

When Helene went to St. Petersburg to recuperate for a while after a strenuous tour, she met Sergei von Schewitsch [alternatively spelled, Shevitch] (1848–1911), whom she had known in passing. Von Schewitsch was in the Russian civil service but was a staunch socialist. They became a couple, emigrated to America in 1877, and married there. Helene von Schewitsch performed in German-language theaters; Sergei became editor of the socialist New Yorker Volkszeitung [New York Newspaper of the People]. But Helene gave up the stage after a few years for the sake of her husband, who suffered from her frequent absences. She turned to medicine and studied at New York University for four years. Shortly before her doctorate, she fell seriously ill and abandoned her plans. She applied herself to writing and painted pictures of flowers to sell.

A decisive event for Helene von Schewitsch during this time was her personal acquaintance, indeed friendship, with Helena Blavatsky, through whom she discovered Theosophy. She described her path in the book Wie ich mein Selbst fand [How I found my Self], published anonymously in 1901. In it, she describes not only a series of spiritualistic experiences but also her encounter with Helena Blavatsky and the basic teachings of Theosophy.

A Tragic Death

In 1890, the couple returned to Europe, partly because Sergei von Schewitsch had to protect the rights to his land in Russia, which had been temporarily revoked. They lived in Riga for a while. After Helene fell seriously ill, they travelled for several years until they settled in Munich.

In 1903, Helene von Schewitsch invited Rudolf Steiner to give a lecture in her home and stated in the invitation letter that, as she was “personally friends with all our authoritative Theosophical leaders,” she did not want to join any particular Theosophical Society: “I want to hold myself free, but devote my life, force, and work to the cause!”7 On March 5, 1904, she wrote to Rudolf Steiner: “To my great joy, dear, so greatly revered Doctor, I hear that you want to give us the next Saturday at 4:30 p.m. for a conference at my home!” In a subsequent letter, she even referred to him as a “friend.” In the autumn of 1905, she sent him a long article on “Die Geheimlehre und die Tiermenschen der modernen Wissenschaft” [The Secret Doctrine and the animal-men of modern science], which followed on from Jörg Lanz von Liebenfels’ remarks. Rudolf Steiner published her article in three parts in Lucifer-Gnosis (1905/06) but subsequently added his own comments in which he contradicted her views. He pointed out the dangers of interpreting higher insights too materialistically8 and wrote: “I have . . . not concealed from the author that I will openly express my opinion on the matter after it has been printed.”9 He presumably spoke to her personally about this because in a letter dated February 6, 1906, Helene von Schewitsch thanked him “for the extraordinarily interesting private afternoon that you devoted to us in my apartment.”

On October 11, 1907, in a card to Marie von Sivers, she sent her regards to the “highly esteemed Herr Dr. Steiner,” after which there is no further evidence of their correspondence. This may have been due to her recurring illness; in addition, the couple became impoverished over the next few years—to the point where they were completely overindebted. It is likely that it was on this account that Sergei von Schewitsch committed suicide on September 27, 191110—and a few days later, on October 1, 1911, his wife took poison. One senses the deep tragedy of this act when one reads what she had written about suicide in 1901: that it was considered “one of the gravest sins of the theosophical secret doctrine.” The one committing suicide “not only does not escape the suffering he flees, but he heaps worse upon himself.”11 Two months later, Rudolf Steiner commemorated her with the words: “I consider it my special duty today to commemorate here the departure from the physical plane of a personage who was well known in all theosophical circles, who was torn from us by a painful death, who worked much, whom we . . . think of with love . . . . You know her books and I need not characterise them in detail. I must emphasise that the circumstances were such that I always rendered her request when she bid me to hold a lecture in her circle during my stays in Munich. I would only like to point out that for me, myself, this whole life shows itself as something deeply tragic, and I may well say that Mrs. von Schewitsch was extraordinarily trusting towards me and that I am justified in saying: This life had profound tragedy.”12

He also mentions her later in his autobiography as “an interesting personage” who represented “a significant piece of history” for him: “Indeed, she was the lady because of whom Ferdinand Lassalle met his untimely end in a duel against a Romanian. She later went on to pursue a career as an actor and became friends with H. P. Blavatsky and Olcott in America. She was a worldly lady whose interests were deeply spiritual at the time when my lectures took place at her home. The strong experiences she had had gave her bearing and an extraordinary weight to what she put forward. Through her, I would like to say, I was able to see the work of Lassalle and his epoch, and through her, some of the characteristic features of H. P. Blavatsky’s life. What she said was subjectively coloured, often arbitrarily formed by fantasy; but, when one took that into account, one could still see the truth through some of the veiling, and one had before oneself the revelation of an uncommon personality.”13

Translation Joshua Kelberman

Footnotes

- Alfred Meebold, Erinnerungen an einen Geistesriesen [Memories of a spiritual giant] (Unpublished manuscript, 1938), typescript.

- There is another notable connection: Her youngest sister Agnes was the mother of Raffaela Paulucci delle Roncole (1875), who married the publisher Felix Heinemann (1863–1935). Heinemann met Rudolf Steiner in the 1890s and turned to anthroposophy in 1917. See Martina Maria Sam, “‘The Most Unforgettable Thing Was His Eyes . . . .’ Felix Heinemann and Rudolf Steiner,” Goetheanum Weekly Issue 16 (Apr. 18, 2024), footnote 2.

- Princess Helene von Racowitza [von Schewitsch], An Autobiography (New York: Macmillan, 1910), 23. Originally published in German as Von anderen und mir: Erinnerungen aller Art [Of others and myself: memories of all kinds] (Berlin: Verlag von Gebrüder Paetel, 1909).

- “[Josef Maria von] Radowitz intended to withhold political equality from the workers. Their interests, he believed, would best be safeguarded by a ‘social kingdom’ (soziales Königtum), a form of government that would be compatible with the patrimonial principle in the solution of the social question. (The theory of the ‘social kingdom’ was also put forth by Lorenz von Stein). In this ‘social kingdom,’ the monarch would actively support the demands of the ‘fourth estate’ and try to better their material position—he would become a king of the poor, so to speak—and his own position would in return be strengthened by the lower classes, who would support him against the demands of the liberal bourgeoisie.” Hermann Beck, The Origins of the Authoritarian Welfare State in Prussia: Conservatives, Bureaucracy, and the Social Question, 1815–70 (Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 1997), p. 69.—Translator’s note.

- In his article “Bismarck, der Mann des politischen Erfolgs” [Bismarck, the Man of Political Success,” published on August 13, 1898; see Rudolf Steiner, Gesammelte Aufsätze zur Kultur- und Zeitgeschichte 1887-1901 [Collected Essays on Culture and Current Events], GA 31 (Dornach: Rudolf Steiner Verlag, 1989), p. 268. It is evident that Rudolf Steiner also spoke about this later; Alfred Meebold writes in his Memories of a Spiritual Giant (see footnote 1): “Rudolf Steiner only first made us aware much later of the drastic effect Lassalle’s death—for which she [Helene] was the cause—had on Germany’s destiny.”

- Rudolf Steiner, Nationalökonomisches Seminar [National Economics Seminar], GA 341 (Dornach: Rudolf Steiner Verlag, 1986). In particular, he repeatedly emphasised Lassalle’s lecture “Die Wissenschaft und der Arbeiter” [Science and the Worker]; see Ferdinand Lasalle, Science and the Workingmen (New York: The International Library Publishing Co., 1900).

- Letter dated May 14, 1903. All letters are in the Rudolf Steiner Archive, Dornach. (RSA 088).

- See Rudolf Steiner, Lucifer-Gnosis: 1903–1908, GA 34 (Dornach: Rudolf Steiner Verlag, 1987), 500–504; Helene von Schewitsch, “Die Geheimlehre und die Tiermenschen in der modernen Wissenschaft” [The Secret Doctrine and the Animal-Men of modern Science] Lucifer-Gnosis, nos. 29–31 (1905–1906): 535–538, 554–563, 596–603. For Steiner’s editorial comments see Lucifer-Gnosis No. 31–32 (1905–1906): 603, 628–630.

- Rudolf Steiner, GA 34, p. 500 f.

- There are various accounts; there is also talk of appendicitis or cardiac paralysis. But, at the time, the newspapers reported suicide.

- Wie ich mein Selbst fand [How I found my Self], 2nd edn. (Leipzig: M. Altmann, 1911.)

- At the 10th General Assembly of the Theosophical Society in Berlin on Dec. 10, 1911, in Rudolf Steiner, Zur Geschichte der Deutschen Sektion der Theosophischen Gesellschaft 1902–1913 [On the History of the German Section of the Theosophical Society 1902–1913], GA 250 (Dornach: Rudolf Steiner Verlag, 2020), p. 465.

- Rudolf Steiner, Autobiography: Chapters in the Course of My Life, CW 28 (Great Barrington, MA: SteinerBooks, 2006), 238–39.