Surrounded by his family, Pierre Della Negra peacefully departed his earthly life on October 4, 2022. This important figure of French anthroposophy left us gently, leaving behind a remarkable creation: the Foyer Michaël.

Everyone that knew him – either as a student, co-worker, or friend – felt that Della Negra seemed closer to the spiritual world than the earthly world. Whether he was teaching or simply thinking, an entire starry world seemed to be reflected on his large forehead, which was crisscrossed with many vivid lines. Pierre was a trained sculptor, but he sacrificed his artistic vocation to become a teacher of an original anthroposophy. He said that sculpture had taught him to think. Pierre spent hours in his office researching, but no one knew exactly what he was researching. He said that he was working on the Platonic solids, or the geometry of counter space, but he didn’t leave any records and you won’t find any books by him in anthroposophical libraries. What he did leave behind is a living creation, the Foyer Michaël, a social creation, an anthroposophically based training center for youth in the green Bocage des Bourbonnais in central France. In a way, his life is almost inseparable from the biography of this place, in which he poured his heart and soul.

Above all, the life of the heart

In the ’60s, Simone Rihouët-Coroze – then ‹patroness› of anthroposophy in France – was originally concerned about the needs of young people seeking anthroposophy and the desire to continue their education. She was in fact concerned about training the future ‹leaders› of the anthroposophical movement in France. This gave rise to the idea of creating a training course to introduce anthroposophy. Rihouët-Coroze asked Della Negra – who was about 30 years of age at the time – if he wanted to take on the project – he answered in the affirmative. Several years of building and experimentation followed. Under the attentive supervision of Rihouët-Coroze, a rather classical teaching style of anthroposophy developed: the study of books and artistic activities.

Pierre devoted himself to his task, accompanied by his indispensable partner and wife Vivien, whom he had met during her studies at Emerson College in Great Britain. Soon, the youthful team felt the need to emancipate themselves from the paternalism of the older generation: With the desire for creativity and freedom, the couple left the original project and founded a second center, the Sophia Center, which for several years focused all its work on artistic practice. This split arose from the need for their own identity and experiences outside the traditional anthroposophical lifestyle. It was also an expression of an awareness that anthroposophy does not primarily address the head, but above all, the life of the heart; and to address the heart, art in its full range must be given priority. The years of secession were filled with the joy and enthusiasm of pioneers and explorers.

Care for others

However, the social question marked the next step and led to a resumption of the collaboration with Rihouët-Coroze and the project of the Foyer Michaël. For Pierre, the artistic question, although central, was not yet sufficient. To anchor art and anthroposophy in human beings, they needed to be rooted in social life. Everything happens in human encounters. Despite the immense realms in which his thinking moved, Pierre directed all his attention on the focal point of interpersonal space, this substance woven from person to person. For him, this was where the true spiritual substance of the future lay.

Foyer Michaël

An aside: For over 50 years, the Foyer Michaël has offered a year of general orientation as well as artistic and pedagogical training based on anthroposophy. Located in central France, near Moulins-sur-Allier, it was created in 1970 from an initiative of the Paul Coroze Foundation, which has been recognized as a non-profit organization since 1972.

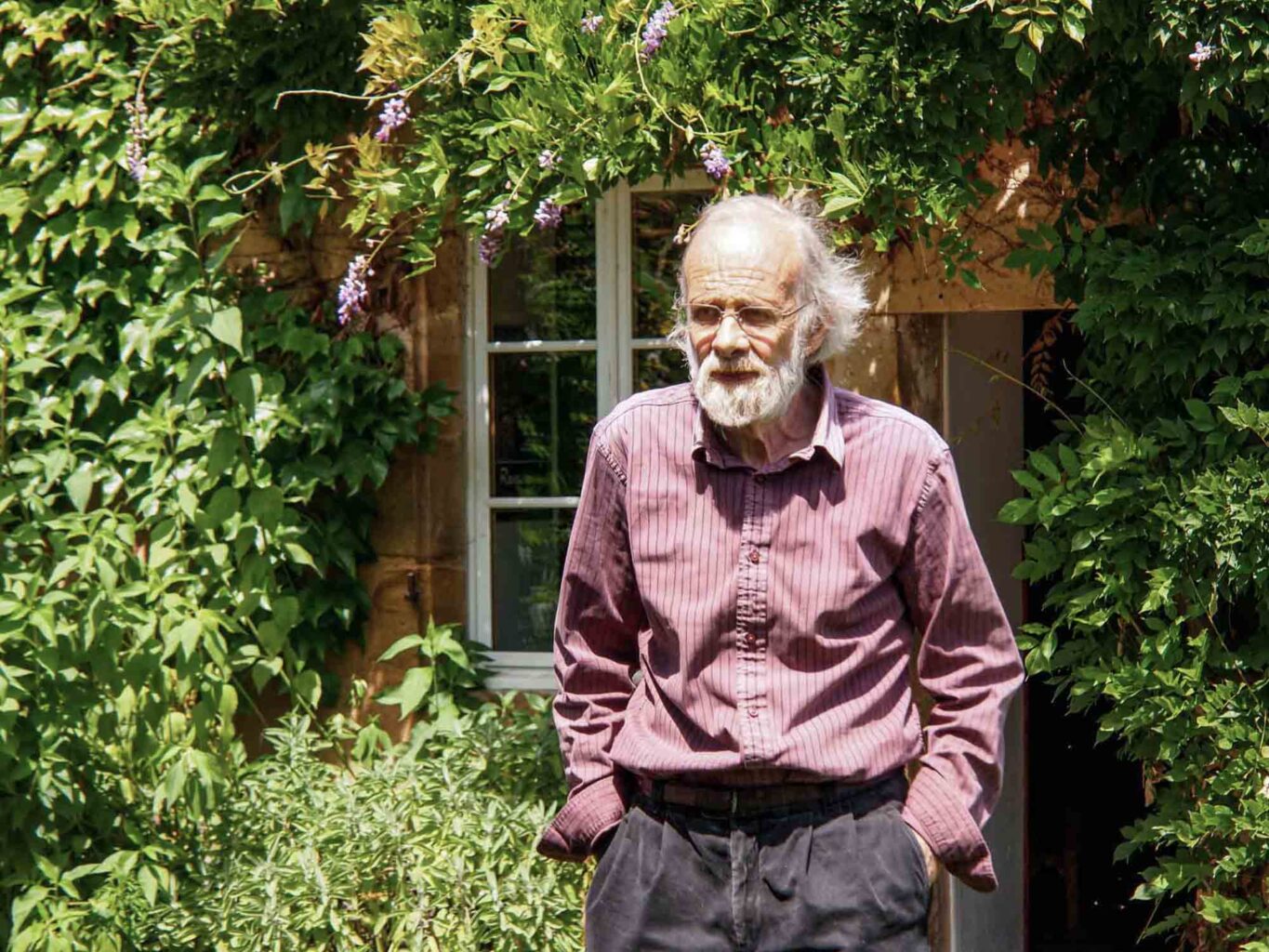

Image: The old building of the Foyer Michaël, seen from the garden.

This social perspective led him to appreciate popular arts such as the chanson and movies, but also the arts of everyday life, the art of the bouquet on the table, or the art of conversation. All this culminated in the highest art: social art. Art must reach everyone in their daily lives. One should experience the human encounter in its difficulty as a space of creation. To see the other as an unfathomable mystery, to sense the sacred in every human story. To look at our neighbor as a ‹wounded› Grail King and ask him inwardly: «What are you suffering from?» We should bear the weight of the troubles of others and see their wounds as their beauty.

Breaths of nature

Pierre kept emphasizing: Let’s try to ‹feel› better. Feeling what lives in other people, what lives in ourselves, but also, and this was another great dimension of his social research: what lives in nature. Pierre was concerned with the rhythm of the seasons. He meditated on the great solar cycle of the earth and the annual festivals. The weekly course in which he shared his experiences and discoveries became a real institution: ‹The Course of the Festivals.› In this course, held for students of the seminary, many people from the surrounding area also came to listen.

To feel the breath of the earth, to accompany it, to open one’s senses, not to project intellectual ideas onto the living, but to learn to be still and to let the phenomena speak – to feel the life of the cosmos through the breaths of nature: Pierre was to become a specialist in this field. For him, Rudolf Steiner’s most important work was the unfinished essay ‹Anthroposophy, a Fragment› – this approach to anthroposophy is based solely on sensory perception. His always modest and tentative contributions, which were consistently based on internal experience, then took on an external form through the organization of the festivities of the annual cycle within the small student community. These colorful celebrations, tactfully and creatively initiated by his wife Vivien, thus became one of the most original and formative components of the education at the Foyer Michaël.

True working-class thinking

When Pierre thought about societal life, he also had in mind the humility of the working class. Therefore, throughout his life, he tried to create progressive societal forms with his partners and associates. The agricultural activities on the farm adjacent to the training center also had an ‹essential› character. Various attempts were made to realize the ideals of a tripartite social life: the collective management of the farm and the creation of production tools to develop an economy that would support the cultural life of the place. Some of these projects failed after many years of hard work. But when an ideal is burning bright, failures are only stages on the way.

Pierre sometimes said that anthroposophy was true ‹working-class thinking,› in contrast to earlier currents of thought that were either aristocratic or bourgeois, that is, borne of the past. Even the thinking of Goethe’s time and its natural philosophy was, for him, still a bourgeois way of thinking due to its social and historical context. So, what is ‹working-class thinking›? It was difficult for him to formulate this. Certainly: the thinking of an exposed, socially deprived human being, cut off from the earth and nature, without social status, a person forced to rely entirely on their own resources, and own individual experience of being human. In his opinion, this was the starting point of anthroposophy, but also the source of true human brotherhood. As a result, he provided an essential insight into the nature of anthroposophy, which is directly embedded in the industrial age and the condition of modern human beings.

Further blossoming

Over the years, trials, joys, and sorrows, this social project has matured and has gradually been taken over by a new, younger team, which today is trying to figure out the next steps in its development. Such social projects are living organisms that cannot remain fixed but are in constant evolution. The Foyer Michaël has been in existence for 50 years now and has welcomed hundreds of young people from all over the world – to have for a year – an intense, social experience based on vibrant artistic exploration and humble and profound thinking-work. In the Foyer Michaël, the aim is to encounter anthroposophy through individual experience, matter, sensory perception, and through others.

Anthroposophy cannot be ‹taught› as one teaches a ready-made theory because it is not an ideology. Anthroposophy is alive. It is born of the encounter, born in the encounter, and is constantly renewed by means of the encounter, with the mystery of the individual uniqueness of the human being at heart, as in a sanctuary. Thanks to his radical anti-dogmatism, Pierre left behind the image of a true anarchist, a ‹wise anarchist› – a man who was grounded in himself and gave his students the taste to conquer their self-confidence and always develop from within themselves. He liked to quote the mystics, especially these words of the German Catholic priest, physician, and religious poet Angelus Silesius, which can also be heard with anarchistic resonance:

The rose is without ‹why›; it blooms simply because it blooms. It pays no attention to itself – it does not ask whether it is seen.

Pierre’s life flourished, and its flowering allowed further blossoming, especially that of this extraordinary place.

Translation Monika Werner