A quantum physicist annotated one of his talks with the following words: «I will tell you things that you understand and that I understand. I will tell you things you don’t understand, but I understand. And finally, things will come up that you don’t understand, and I don’t understand.»

I don’t feel much different, because I look at the evolution of human beings from both an outside and inside perspective. I’ll start with a sketch of Charles Darwin, the founder of the theory of evolution. When I speak of Darwin, I mean the ‹Synthetic Theory› formulated in the 30s of the last century. It aimed to include all disciplines, from anatomy and neurology to immunology and especially genetics.

Charles Darwin

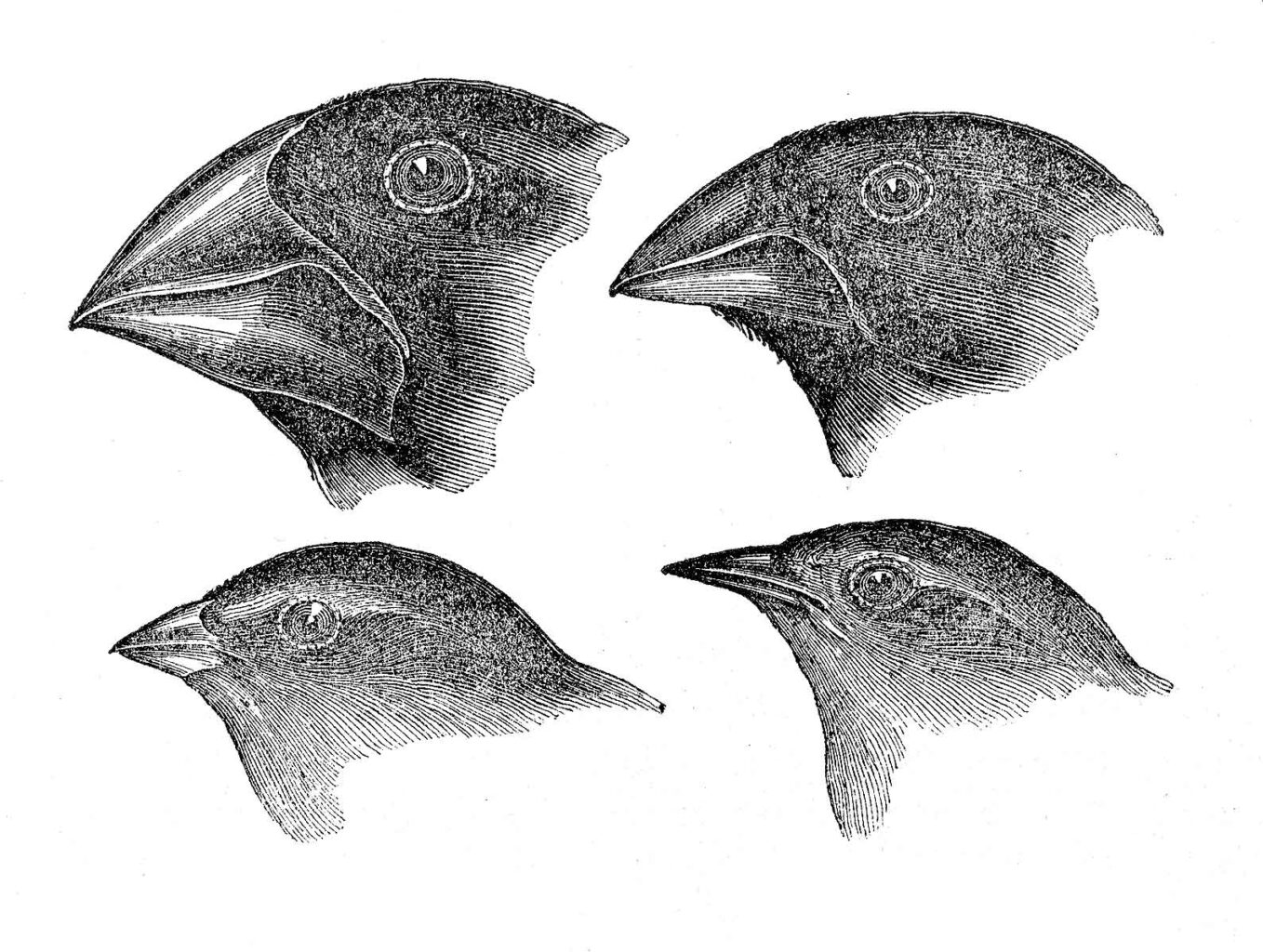

Darwin gave up medical school because he could not dissect corpses. He was a nature lover and close observer and was given the opportunity to spend five years on the Beagle, a Royal Navy survey boat tasked with surveying the coastlines of all British colonies. When the ship anchored on the Chilean cliffs, Darwin observed different fossil mussels in the layers of sediment. He understood a lot about geology and knew that the lowest layer is the oldest and the top is the youngest. Thus, during the ascent, he discovered the change of mussels and other shellfish. On the Galapagos Islands, he noticed slight differences in related bird and plant species on the various islands. He came to the conclusion that a few birds from the South American mainland had arrived on the islands, dispersed, and must have changed shape over time – how is this possible? One of the books he read in his free hours on board was a publication by the English economist Malthus. He speculated about population growth, with which food production would not keep pace. According to Malthus, a struggle for survival seemed inevitable. It would come to a selection of the best adapted, the smartest human beings. This speculation provided the second pillar of the Darwinian theory of evolution: in addition to random variation – the principle of life that produces a diversity of forms – the best-adapted forms would always be sorted out: variation and selection.

The discovery and formulation of this theory did not leave Darwin unaffected. In his biography, he describes his travels through the South American jungle and how he was gripped by wonder, admiration, and reverence for the beauty, wisdom, and complexity of life. «After formulating my theory, I felt like a colorblind person. The beauty, the wonder, the awe were gone!» he writes. He continued: «Even the largest number of people who see colors could not convince me today that colors exist.» With his theory, he lost this reverence for creation and for the beauty of this ecological wisdom. It is important to become aware that thoughts shape inner moods. When Darwin published ‹On the Origin of Species› in 1859, he was not the only one who also thought about how we humans came to Earth. Herder, Goethe writes, had already considered whether human beings could be descendants of the ape.

Twelve years later, Darwin published his book on ‹The Descent of Man› and knew that his theory would knock us humans off the throne of creation. We, humans, are a product of chance – no different from the shrew, who was also created by chance in the course of evolution. The book ‹The Descent of Man› has indeed caused incredible controversy. At that time, it was a sacrilege to push God from the throne as the Creator of human beings. The evolution of human beings leads to the view that humans, just like any plant and animal, are a product of random change and subsequent selection. Darwin’s theory was impressively confirmed by genetic analyses in the 20th century on the relationship between primates, meaning great apes, and humans. It was found, for example, that the genetic similarity of chimpanzees and humans is between 96 and 98.8 percent. It would be absurd to say that man is not in this line of apes. However, the question is whether the story of human development couldn’t be told differently.

What Distinguishes Us From Animals

As an embryologist, Louis Bolk investigated how animals and humans differ. In the process, he discovered pedomorphic and hypermorphic features. Pedomorphic traits are exhibited by every mammal but disappear at birth or sexual maturity – but they are preserved in humans. In hypermorphic traits, humans go beyond anything animals exhibit. The occipital hole in the skull, where the nerve strands pass from the spine to the brain, is one such feature. It is always at the bottom center at the beginning of development, in all mammals, as in humans. However, it moves dorsally, backward, in the course of animal development, but not in human development. The animal skull hangs on its trunk. The human skull rests on its body. Another feature is the compression of the facial skull – a feature that also appears in all animals. Walt Disney discovered this: the animal characters Mickey Mouse and Bambi have round heads. This seems childlike and friendly. All animals have a roundish shape until sexual maturity. In puberty, the snout grows out. We humans keep this facial compression until the end of life. Another feature concerns the hand. All animals start with five-part end limbs. In the course of development, however, a horse retains only one finger, that is, one toe; in cattle, sheep, and goats there are two. Of course, there are also animals that remain with five-limbed end limbs, but these are highly specialized, as in the mole. In humans, the end limbs remain unspecialized! As mentioned, Bolk has also described hypermorphic features. Human beings have relatively short arms and long legs. No monkey has this pronounced difference between the anterior and posterior limbs. The second is the descent of the larynx. As a result, the spectrum of vocalizations in humans is enormous, compared to primates. And finally, no animal has as large an occipital skull as humans. These characteristics are the biological prerequisites for human development. The occipital hole and long legs are prerequisites for an upright gait. The descent of the larynx and the compression of the facial skull are conditions biologically gifted for speaking. If we were to develop a snout, like monkeys, we would have to learn to speak a second time during puberty. Finally, it is also clear what the third pair of features is all about: a large brain, which enables creativity and imagination, depends on a capable hand – be it in art, craft, or technology. The human being is a generalist. This is related to thinking.

Konrad Lorenz once wrote that human beings could do nothing as well as other animals, but they are the only mammal that can walk 30 kilometers in one day, swim 400 meters, dive 6 meters, and then climb 10 meters high on a tree in the evening for the admiration of the sunset. No animal can do that.

Humans can do everything a little, but by no means to perfection, such as the bear climbing the tree or the cheetah flying over the steppe. But it remains free – the physical conditions for upright walking, language and thought are gifted to human beings. One can only acquire the skills for being upright, speaking, and thinking in a community of people where people walk upright, speak, and hopefully, also think.

King Frederick II wanted to find out what the original language of human beings was. He assumed it was Hebrew. To figure out, he had children raised by mute nurses. However, these children only babbled, if they survived at all. The same applies to thinking – it only develops when others think around the child. This also applies to the first elementary skill we learn after birth, which is to stand upright. Only later speaking and finally thinking follow. Human development took place through the long history of evolution in exactly this order: about seven million years ago, ape-like beings began walking on two legs. Anthropologists suspect that language originated about 300,000 years ago. The modern, thinking human being has probably only been around for about 40,000 years. Around then, we have evidence that thought was not exhausted by daily affairs – the presence of funeral rites shows that people had begun to think about death, and that which exists beyond life. A little later, they created sacred statuettes such as the Venus of Holhe Fels and art objects like the first flute from vulture wing bones.

Where Does Freedom Begin?

For René Descartes, it was evident that plants, animals, and the human body are all automatons, machines. Only through thought – cogito ergo sum – does the body become spirit and fully human. Starting from this dualism – machine vs. spirit – the philosopher Hans Jonas considers how the mind gradually develops out of a determined, machine-like being. For this, he puts forward a provocative hypothesis, because at no stage of development does the ‹mind› suddenly appear, out of nowhere. With his hypothesis, he turns the current theory of evolution upside down: «Let’s think about evolution not from animals to humans, but from humans back to animals!» What distinguishes a human being is inwardness, which can actually be discovered in all life. It, and thus ‹spirit›, which finds its highest expression in human beings as freedom, must also be found in preliminary forms in plants and animals.

The first moment of freedom he discovers in living nature is metabolism. Matter passes through an organism without changing it. On the contrary, it is there to maintain shape, biological functions, and processes. This property is characteristic of all microbes and plants. He finds the second moment of freedom in animals, who are also able to perceive, move, and form a life of sensation. Anyone who has observed animals knows that you can approach them up to a certain distance without them moving. If you get too close to them, they flee. With birds like blackbirds and crows, you can experience that they stay calm as long as you walk but fly away as soon as you stop. They perceive something, judge the quality of perception, and when they feel that danger is imminent, fly away. Of course, the blackbird is not totally free, and the plant is much less so, but with Jonas, you can qualitatively find such elements related to freedom in non-human nature.

Jonas’ conclusions represent a challenge, a no-go: if preliminary freedom also exists in non-human nature, then in the evolution of human beings, there is a kind of purpose, teleology, or goal! This is just as frowned upon in the materialistic, academic natural sciences as it is amongst the Goetheanists. The question is then: How can freedom become out of a determined being? That is only possible if it is already present germinally from the beginning as potential. In addition, he says that teleology is, of course, action, the action of human beings themselves. We rarely do anything without intention. It is interesting that even though all machines and mechanisms and apparatuses correspond to all the laws of nature – otherwise they would not work – at the same time they are built for a specific purpose. Georg Michael Pfaff wanted a sewing machine, Karl Benz a motor vehicle. The problem, I think, is not that one thinks teleologically, but that one thinks that there is causally only one possibility, as with the first causes. But ‹Telos› opens a variety of possibilities! With every development I make, the goal I aim for changes a little, and with every new situation outside, there is also a corresponding adjustment. Telos is a kind of direction that we are approaching. For Hans Jonas, it was clear: even we humans have not reached the end of the line, this ability of freedom, this ability of compassion or empathy – rather, the capacity of free will can and must be further developed. This is also reflected in the new ideas of genetics and epigenetics. First, something is done by the living being, which is later internalized and appears in later generations as an inherited characteristic. This means that living beings are not only victims of their genetic makeup – they play with this material. In the epilogue of his book, Jonas writes: «The philosophy of mind includes ethics. And through the continuity of the mind with the organism and the organism with nature, ethics becomes a part of nature.» I’ll come back to that at the end. Jonas goes on to talk about ideas and morality: «It doesn’t follow from what I said, that an idea has to be an invention and cannot be a discovery.» He has grasped a thought that is very valuable in the Anthroposophical view: the terms and ideas are not inventions, but they exist, and we ‹discover› them. Thinking does not mean inventing new terms, but discovering them through training.

So That Life Can Embody Itself

In his younger years, Rudolf Steiner dealt intensively with Goethe. He edited the first edition of the ‹Naturwissenschaftliche Schriften› (Scientific Writings) and thought a lot about Goethe’s method of knowledge. In the ‹An Outline of an Epistemology of Goethe’s Worldview›, he comes out as a Darwinist, a critical Darwinist. Of course, Darwin is right when he says that an animal form with the properties A, B, and C comes to the properties A’, B’, and C’ due to changed environmental conditions. But, he continues, Darwinism cannot say anything about how properties A, B, and C came into being in the first place. And I think, since I have a relatively good overview of this area, I can say that it is still not known today. In order for plants or animals with certain characteristics to emerge, an agent – an effective idea, according to Goethea, such as the primordial plant or animal – is needed, which actively produces constituent living beings. But they cannot appear – as Goethe emphasizes – unless there are external conditions which modify this operative idea. We learn that if we want to understand living beings, we need the conceptual component alongside this generative power, and we need the external world so that they can embody themselves here on earth. Goethe cautiously speculates about the origin of life and the position of human beings. There would be a life point, whether plant or animal, that was not determined. In the light, this life source becomes the plant that hardens into the tree, and in the darkness, this life point becomes the animal that specializes and unites. In the end, human beings, with their full potential for freedom, finally emerge, consciously returning to the source of life.

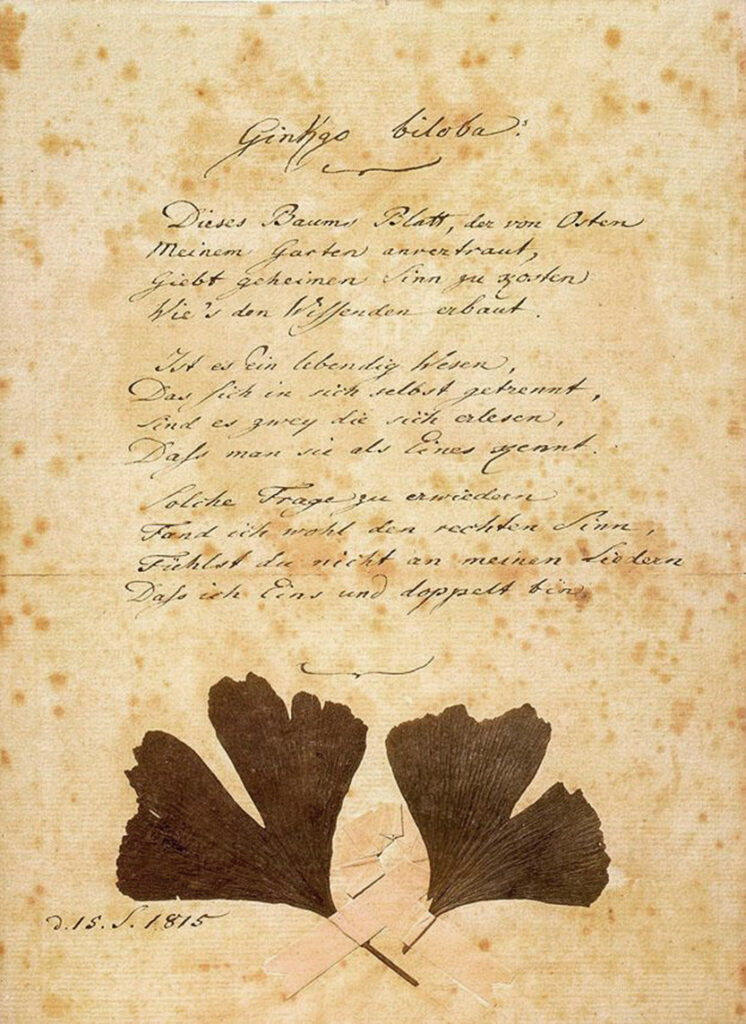

This tree leaf entrusted from the East / To my garden, / Gives secret meaning to taste, / How it is built for the knower, / Is it a living being, / That separates itself in itself? / Are there two who choose each other, / That they are known as One? / To repeat such a question, / Did I find the right sense, / Do you not feel in my songs, / That I am one and double?

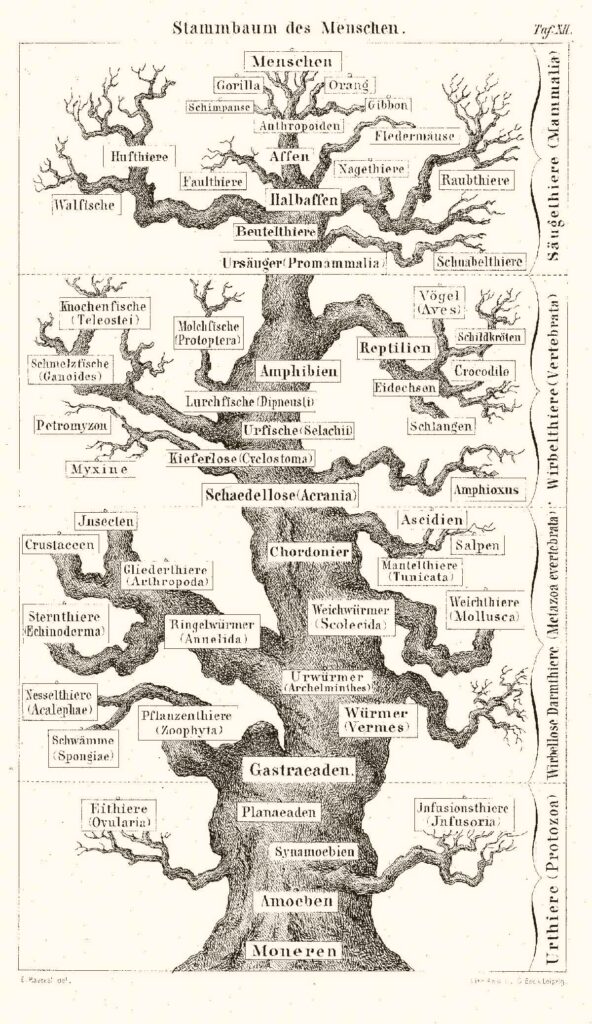

The ideas of Goethe and Darwin were assured facts for Rudolf Steiner until the beginning of the 20th century. In the early days of the theory of evolution, the origin of living beings up to humans was summarized in a family tree. The most vehement representative of Darwin’s ideas in Germany was Ernst Haeckel, who Steiner appreciated, but recognized his limits. The Haeckel family tree was, of course, an oak tree. Along the trunk, on the branches near the ground, you can see invertebrates. This is followed by fish on the next main branch, which splits off, then amphibians, reptiles, and birds, and finally against the crown of the gnarled tree, mammals. At the very top of the crown, on the outermost branches, appear the primates, orangutans, gorillas, chimpanzees, and bonobos, and on one side branch, the human. Such was the idea of the family tree, which started mightily down there, of course, with unicellular organisms and bacteria.

Older Than All Other Living Beings

In Chapter 30 of his biography, ‹Chapters in the Course of My Life,› Rudolf Steiner writes: «The real development of the organic, from primeval times to the present, stood before my imagination only after the elaboration of my ‹world and life views›.» Today this book is called ‹Riddles of Philosophy›. «During this time, I still had the scientific view in front of the soul’s eye, which had emerged from Darwin’s way of thinking. However, I only considered this to be a series of obvious facts, present in nature. Within this series of facts, spiritual impulses were active for me [such as the idea of the Typus], as Goethe had in mind in his Metamorphose idea… I saw Darwinism as a way of thinking that is on its way to Goetheanism, but lagging behind it… I only worked my way through to the imaginative view later. Only this view brought me the realization that, in primeval times, in spiritual reality, there was something completely different from the simplest organisms. That human beings, as spirit beings, are older than all other living beings, and that in order to take on our present physical form, we had to separate human beings from a world being that contained them and the other organisms. These are therefore byproducts of human development; not something from which humans emerged, but something humans left behind, separated from themselves to take on their physical form as an image of their spirit. Only in the first years of the new century did I realize that the human being is a macrocosmic being, who carried all the rest of the earthly world within itself and came into the microcosm by separating the rest.»

One can see this dramatic transformation. The spiritual world is not far away, but present. We just do not yet have the organs to notice it. It is constantly active. This macrocosmic human being is moving towards the Earth and on this path to where it will embody itself as a microcosmic, earthly human being – that’s how I understand Rudolf Steiner. The byproducts are the intellectual possibilities that become the lifepoints Goethe thought about. When life unfolds at these source sites, what Darwin described happens: different forms of worms or insects or other primitive animals develop, and in further evolution also higher animals, vertebrates, and mammals. All these animal forms are left behind by the spiritual human being to be able to embody itself here on Earth. But after having ‘purified’ itself mentally so far, it has to look for a suitable ancestor, monkey ancestor, into whom it can embody itself.

This is the opposite process of the one you think is Darwinistic. It is not a development from worm to human, but a human’s will to incarnate enables other beings to participate in evolution. The first, spiritually, will be the last physically. The family tree must be drawn in reverse: from heaven to earth – this is how I interpret this passage.

Three Ways

Such an inverted way of understanding evolution puts today’s questions of climate change, biodiversity, and hunger in a new light. It could provide the key to closing the gap between knowledge and action. Against the background of Rudolf Steiner’s Anthroposophy, I would like to outline three relevant aspects. Rudolf Steiner describes the first result or fruit of the so-called Rosicrucian meditation to be noticing a split of the personality between one’s everyday self and higher I. I am not only the one my persona knows, but there is another, higher I to sense. Can this sensing become knowledge? If this succeeds, we can consciously begin to recognize that our biographical path has a direction or goal, like the evolution of human beings from the cosmic to an earthly self-described by Steiner. We, as individuals on Earth, can also develop the ability to consciously move ‹forward› back to our origin.

If it is indeed the case that we are co-creators of our living world and are involved in the creation that now surrounds and sustains us, then we are neither rulers of this world nor administrators or partners, but participants. If we understand and feel this point, we will learn to deal with the Earth differently than if we understood the Earth as a pool of resources. We will notice that to the extent that what we have worked to create is oppressed or threatened by us today, we ourselves are harassed or threatened. And the reverse is also true, that whatever good we create will also create something good in the world outside. I would like to give the floor once again to Hans Jonas: «The philosophy of mind includes ethics, and through the continuity of the mind with the organism and the organism with nature, ethics becomes a part of the philosophy of nature.» It could mean that if we want to act ethically or well, we don’t just have our fellow human beings in mind. We realize that this kind of ethics must benefit our nature.

Conversely, if ethics are also part of external nature, it is worthwhile to turn to this more-than-human nature in order to find, not only natural laws and beauty, but also instructions for good action. The image of evolution beginning in the spiritual with the human standing first has different implications than the classical picture, where the human appears last and can appropriate the Earth.

If we start from the higher human being, we see that we are participants of nature and that within it, in addition to the visible natural law, all artistry, all morality, and ethics are hidden. I am convinced that we can deal sensibly with challenges such as climate change, biodiversity loss, and poverty if we think of creation from the will to incarnate of cosmic humans. Thus, all of nature is an expression of our humanity.

The article is an abbreviated version of the video lecture in the series ‹Anthroposophy – an extension of science?›, held on February 14, 2022. Available at goetheanum.tv. – Translation: Monika Werner

Cover PictureAedrian from unsplash

So interesting.