Shortly after Rudolf Steiner’s death, the art critic Max Osborn recounted an incident during his time as editor of the Magazin für Litteratur [Magazine for Literature]:1 “One day, we all received a strange letter, in which the mighty master of the Magazine communicated to us that, unfortunately, something fatal had occurred. As he, Steiner, tried to light his pipe last night, the whole desk went up in flames. ‘Should you, dear sir, suppose that I still have any unanswered letters or outstanding manuscripts, I can only deeply regret . . . .’ No one has ever found out what happened on that horrible night . . . .”2

Some evidence of the fire does exist that allows us to date the event, at least approximately, to the last days of September 1898.3 The fire was certainly not large; presumably, it was limited to the desk—Rudolf Steiner was probably able to extinguish it on his own. But, to be sure, the fire still destroyed enough manuscripts that the editor had to send the “letter” mentioned above by Max Osborn to his authors. At the time, Rudolf Steiner’s “editorial office” was his desk in the apartment at Habsburgerstrasse 11 in Berlin, in which he had been living again with Anna Eunike since the beginning of May 1898 after the two had lived separately in different places since the sale of the house in Weimar in October 1896. The desk certainly looked similar to the one in the (next) apartment on Kaiserallee, of which Alwin Alfred Rudolph recounts: “. . . [A]t the window, a desk of gigantic dimensions, overloaded with papers and books. . . . Only right in front of the chair was there a free space for a sheet of paper. And there he wrote.”4 In any case, this fire marked a point in Rudolf Steiner’s life, wherein he had to go through all kinds of difficulties and was in a deep crisis.

Professional Crisis

For nearly more than a year, he had been running the Magazin für Litteratur [Magazine for Literature]—and this had not been a good year for him. The number of subscribers was falling, and Rudolf Steiner came into great conflict with his publisher, Emil Felber (who was in Weimar). Felber had published his books The Philosophy of Spiritual Activity, Friedrich Nietzsche: Fighter for Freedom, and Goethe’s World View5 and had also taken over the Magazine for Literature when Rudolf Steiner began editing it. Very quickly, however, the two clashed. Felber complained that manuscripts were sent in too late, that too many errors were overlooked in the articles, that the honorariums were too high, that the 1897 annual report was produced too late, etc.

More and more, the authors repeatedly complained to Rudolf Steiner that they were not receiving their honorariums from Felber. On September 7, 1898—a few weeks before the desk fire—Rudolf Steiner wrote to Emil Felber in remarkably sharp terms: “The matter has now come to the point where I . . . receive almost daily complaints about outstanding honorariums . . . . But, you write offensive letters to me and request Mr. Häfker to stop writing in the magazine while you are publishing it. Whether or not you now agree with my editorial leadership, one thing is certain: you could have written me polite letters during this year. Nonetheless, none of that is an option at the moment. You, yourself, applied for the job with the magazine, and I could not and should not assume that you would let me down in a year’s time in the way you have done.”7

Already at the end of June 1898, Felber had announced that his contract with the Magazine for Literature would terminate in October. Thereupon, Rudolf Steiner seriously considered whether he should give up the Magazine altogether and start something else. One possibility opened up for him when his relationship with the Nietzsche Archive was revived. Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche made renewed efforts towards retaining Rudolf Steiner because she viewed him as the most suitable editor. In view of his professional crisis, he also was not disinclined, as can be seen from his letter to Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche on June 27, 1898, which was surprisingly accommodating following the previous events.8 However, she set him the condition that he should write a kind of “confession of guilt” for the crisis that occurred in the Nietzsche Archive in December 1896. This was ultimately too much for Rudolf Steiner. And so, he wrote her a definitive rejection on August 23, 1898: “With regard to the matter, I must still maintain that I was not to blame for any of the events. I did nothing to bring about these incidents nor to make them so unpleasant.”

No Political Views

A further significant experience for Rudolf Steiner fell precisely at this point of time at the end of September. On September 30, 1898, an “open exchange of letters” between John Henry Mackay and Rudolf Steiner appeared in the Magazine for Literature. He met Mackay through Gabriele Reuter in Weimar, and he shared a great enthusiasm for Max Stirner and his radical individualism. Rudolf Steiner wrote to John Henry Mackay on December 5, 1893, that he perceived the first part of his Philosophy of Spiritual Activity as the “philosophical fundament for the Stirnarian outlook on life. What I develop in the second half of the Philosophy of Spiritual Activity as the ethical consequence of my premises is, I believe, in perfect agreement with the statements in the book The Unique and Its Own [Der Einzige und sein Eigentum].”9

But, it was precisely this individualism of Stirner, as represented by Mackay, that was to become a test for Steiner: “Destiny had now turned my experience with J. H. Mackay and with Stirner in such a way that I then had to immerse myself in a world of thought that became a spiritual test for me. My ethical individualism was perceived as a purely inner experience of the human being. When I developed it, it was nowhere near my intention to make it the basis of a political view. At that time, round around 1898, my soul was to be torn into a kind of abyss by purely ethical individualism. It was to be turned from something purely human and inward into something external.”10

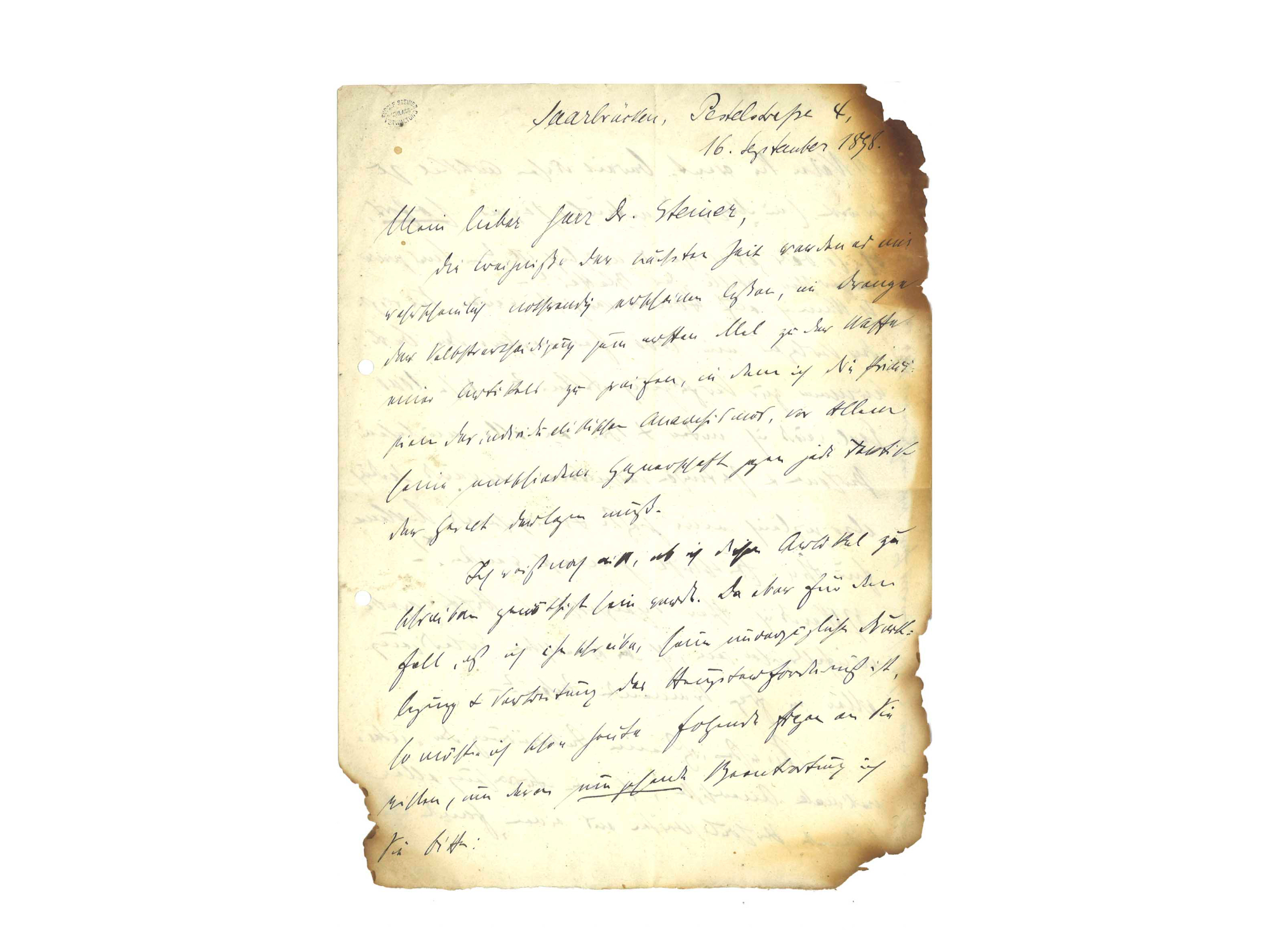

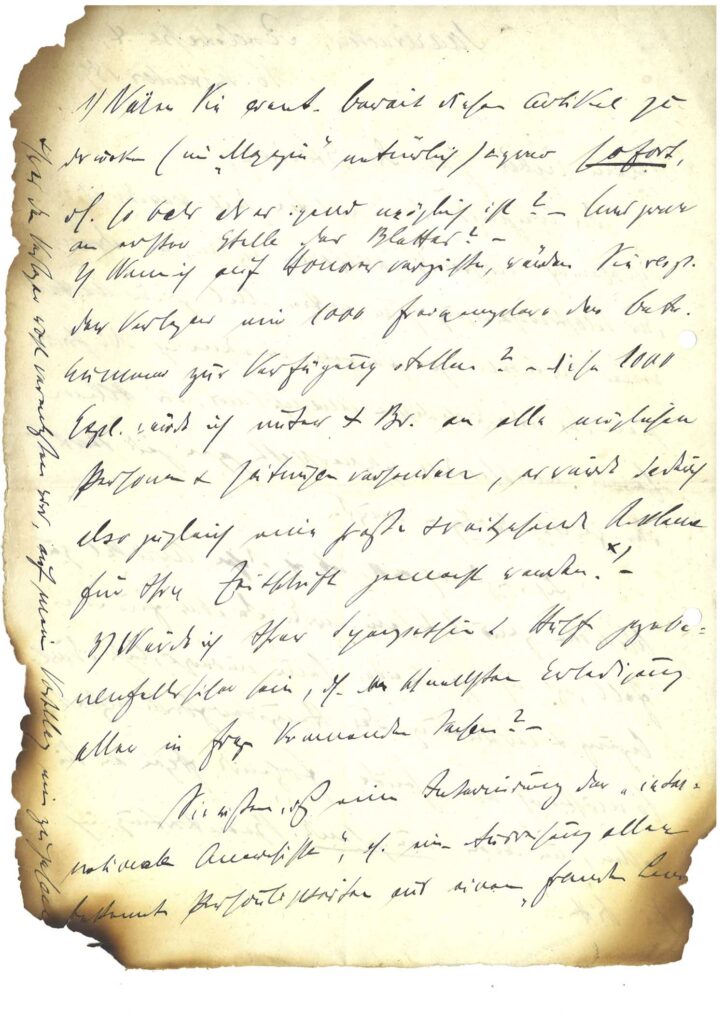

Rudolf Steiner is surely pointing here to something that becomes apparent in the open exchange of letters between him and John Henry Mackay. After the uproar caused by the events of September 10, 1898—the Empress Elisabeth of Austria (“Sissi”) had been murdered by the Italian anarchist Luigi Lucheni, who described himself as an “individualist anarchist”—Mackay, as the author of a work entitled The Anarchists, was probably afraid of being expelled from Germany. He wrote to Rudolf Steiner on September 16, 1898, in one of those letters burned in the desk fire: “You know that an internment is planned for the “international anarchists,” i.e., an expulsion of all known personages from a ‘foreign country.’ I have little to do now with the Communists, who—in this time of idiocy and sheer madness—still asks about that? But I have serious reasons that compel me, if not to live in Germany, at least not to allow the coming reaction to deny me entry into our country.”11 Thereupon, he requested an open letter to be printed as the lead article in an issue of the Magazine for Literature. In this “Letter,” he takes a stand against the “tactics of violence,” “so as not to see my name thrown together with those ‘anarchists’ who are not anarchists, but rather, one and all, revolutionary communists.”

In the Line of Fire

Rudolf Steiner likewise answered him in another “open letter” in the same issue, saying that he had previously avoided implementing the phrase “individualist anarchism” to describe his world view, but that he now must say that he could be described as an “individualist anarchist.” This anarchism, however, is different from that which pays homage to the “propaganda of the deed.” He writes: “The ‘individualist anarchist’ wants that no person be prevented by anything from being able to unfold the abilities and powers that lie within him. The individual will assert themselves in a fully free competitive struggle. . . . The individualist anarchist . . . knows this one thing: by abrogating all violence and authority, one, thereby, makes the way free for the most independent human beings.—But the present states are founded on violence and authority. The individualist anarchist is adverse to them because they suppress freedom. He wants nothing but the free, unhindered unfolding of forces. . . . He fights the violence that suppresses freedom, and he fights just as much when the state violates the idealist’s idea of freedom, as when an idiotic, vain brute maliciously assassinates the sympathetic enthusiast on the Austrian imperial throne.”12

While Mackay wanted to take himself “out of the line of fire” to a certain extent with his article, Rudolf Steiner, with his attack on the state and his confession of “individualist anarchism,” consciously put himself into it. A few years later, Karl Vorländer still described Rudolf Steiner as Mackay’s “shield-bearer,” and both together as “literary-anarchist salon-Tyroleans (!).”13 Thus, this open exchange of letters was published on September 30, 1898, in No. 39 of the Magazine for Literature—in the last issue under the publisher Emil Felber. No. 40 from October 8, 1898 was already published by Siegried Cronbach; the contract is dated September 27, 1898.14

Tests of Fire

The whole process most probably belonged to the spiritual trial of 1898, about which Rudolf Steiner wrote in his Autobiography, as mentioned above. He goes on to say: “At the beginning of the new century, when I could then give my experience of the spirit in writings such as Mystics at the Dawn of the Modern Age and Christianity as Mystical Fact, ‘ethical individualism’ stood, after the test, once again in its right place. But still, even then [1898], the test proceeded so that, in full consciousness, the externalizing played no role. It proceeded directly with this full consciousness, and, indeed, precisely because of this proximity could it flow into the forms of expression in which I spoke of social things in the last years of the last century. . . . My inner experience at that time was an inner movement that brought all my soul forces into waves and surges.”15

Rudolf Steiner had three significant “fire” experiences in his life: As a small boy, around 1865, when a railroad train with a burning coach pulled into the station; secondly, the desk fire in the year of his “abyss experience” 1898; and, finally, the most incisive and painful fire event—the burning of the Goetheanum on New Year’s Eve 1922. Perhaps, the event of the desk fire can be read in this context of fate as a beacon—as the first awakening experience on the path that allowed Rudolf Steiner to overcome the abyss in the following years?

Translation Joshua Kelberman

Footnotes

- Max Osborn, “Erinnerungen” [Memories], Vossischen Zeitung [Voss’s Newspaper] (April 1, 1925), morning edition.

- Max Osborn published an article in the Magazin on September 24, 1898, with the title “Unser München I” [Our Munich I]. It can, therefore, be assumed that the sequel, “Unser München II” [Our Munich II], was a victim of the flames.

- Several singed letters and books exist, as well as a letter from Moritz Zitter dated October 6, 1898, who, waiting for a promised letter, writes: “Has the fire in your room also used up the final remains of your letter writing energy?”

- Alwin Alfred Rudolph and Johanna Mücke, Erinnerungen an Rudolf Steiner und seine Wirksamkeit in der Arbeiterbildungsschule in Berlin 1899–1904 [Memories of Rudolf Steiner and his Efficacy at the Worker Education School in Berlin 1899–1904] (Basel: Zbinden, 1979), pp. 44 and 55.

- Rudolf Steiner, The Philosophy of Spiritual Activity, CW 4 (Tiburon, CA: Chadwick Library Press, 2020); Friedrich Nietzsche: Fighter for Freedom, CW 5 (Englewood, NJ: Rudolf Steiner Publications, 1960); Goethe’s Theory of Knowledge, CW 2 (Tiburon, CA: Chadwick Library Press, 2021).

- Rudolf Steiner Archive (abbreviated “RSA” in the following). Interestingly, one of the books with traces of fire that has been preserved in Rudolf Steiner’s library is the book by Dreyfus: Briefe aus der Gefangenschaft [Letters from internment] (Berlin: Siegfried Cronbach, 1899), whose publication by the Cronbach publishing house was reported in the Börsenblatt des deutschen Buchhandels [Trade sheet of the German book trade] of Sept. 26, 1898. Rudolf Steiner had presumably received a copy hot off the press from Siegfried Cronbach when the contract was signed on Sept. 27, 1898. Other books that were probably burned at the time were Emil Reich, Henrik Ibsen’s Dramen [Henrik Ibsen’s Dramas] (Dresden and Leipzig: Pierson, 1894); Robert Zimmermann, Über das Tragische und die Tragödie [On the tragic and the tragedy] (Vienna: Wilhelm Braumüller, 1856).

- RSA. This letter will appear in Volume 3 of the Sämtliche Briefe [Collected Letters], GA 38/3. In the course of 1898, Rudolf Steiner sued Emil Felber for overdue honorariums. The case was to drag on until 1907 and end with a settlement.

- Rudolf Steiner, Briefe Band II [Letters Volume II]: 1890–1925, GA 39, 2nd edn. (Dornach: Rudolf Steiner Verlag, 1987), pp. 362–364.

- Rudolf Steiner, Sämtliche Briefe 2 [Collected Letters 2], GA 38/2 (Basel: Rudolf Steiner, 2023), p. 528. Cf. on this topic the essay: David Marc Hoffmann, Rudolf Steiners Auseinandersetzung mit Max Stirner und Friedrich Nietzsche und ihre Bedeutung für das Entstehen der Anthroposophie [Rudolf Steiner’s debate with Max Stirner and Friedrich Nietzsche and its significance for the emergence of anthroposophy], in Jost Schieren, ed., Die philosophischen Quellen der Anthroposophie [The philosophical sources of anthroposophy] (Frankfurt: Info3, 2022), pp. 191–223. See also, Max Stirner, The Ego and Its Own (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1995).

- Rudolf Steiner, Autobiography: Chapters in the Course of My Life, 1861–1907, CW 28 (Great Barrington, MA: SteinerBooks, 2005).

- RSA.

- The two letters are reprinted in Briefe Band II [Letters Volume II]: 1890–1925, GA 39, 2nd edn. (Dornach: Rudolf Steiner Verlag, 1987), pp. 368–373.

- In Zeitschrift für Philosophie und philosophische Kritik, vol. 119 (Leipzig: 1902), p. 209.

- Another kind of “open exchange of letters” had taken place almost simultaneously in numbers 38 and 40 of the Dramaturgische Blätter [Dramaturgical Sheets]—dated Sept. 24 and Oct. 8, 1898—which were enclosed with the Magazine for Literature at the time. Rainer Maria Rilke had written an article on the “Wert des Monologes” [Value of the monologue]. Rudolf Steiner appended a few remarks, to which Rilke replied with “Noch ein Wort über den ‘Wert des Monologs’” [One more word about the ‘Value of the monologue.’] So this, too, in these momentous weeks.

- See note 10. Rudolf Steiner, Mystics at the Dawn of the Modern Age (Tiburon, CA: Chadwick Library Press, 2018); Christianity as Mystical Fact and the Mysteries of Antiquity (Tiburon, CA: Chadwick Library Press, 2021).