Tenderness is an opportunity to walk through darkness and become a small light that illuminates the world. Through a conversation about the artistic work of “Pink and the Rest of the World,” a group initiated by Gilda Bartel in Weimar, and a reflection on Eastertime, Gilda and Franka Henn seek a context for tenderness and its significance.

Franka Henn: How did “Pink and the Rest of the World” come about?

Gilda Bartel I’ve been working artistically with vulnerability and tenderness for a long time. So I took as my starting point the color pink, on one hand, and my own experiences, on the other. In bringing together this workshop, I hoped to create a framework in which I could work artistically with other people. How can one grasp aesthetically what is tender, vulnerable, and delicate, even in its dignity? Nine artists are currently taking part.

Do you have a goal in mind?

My motivation was to exchange ideas with other artists. Originally, I’d thought of making it a presentation weekend to show my work and have conversations about tenderness. It’s grown since then. Delicate connections have been made that could lead to a touring exhibition and other artists joining in. Talking about tenderness and bringing vulnerability into the conversation seems, to me, to make sense for our time. Art is a beautiful medium for doing this.

Why “tenderness” for you, now?

The world has become so loud, noisy, fast, even brutal. It feels raw, populist, scared, and overly simplistic, in a way. Capitalism is eating us up, and not just in Europe. I don’t want to describe it in polar terms, but it seems to me that tenderness is a counterweight to all this. Turning to tenderness can be an advantage. For me, it’s about exploring what is tender and coming into contact with it. Like everybody, I myself have to run around the world, support my children, work, etc. So, where am I tender? How could I transform the qualities of my own tenderness and shyness into something that supports me in a different way? Why can’t I do this very well? How different do I feel about myself when I stand in my own tenderness? How differently do I handle my child, my dog, my washing up? What exactly is tender thinking?

There is huge scope for exploration into and with tenderness. It is something that works within me and something I am. On the other hand, it is also a quality through which other things become perceptible or appear differently. I can capture, visualize, and understand this space by working artistically. At the same time, I can only work artistically out of my own tenderness. I came up with the term “light-skin” in Iceland when I saw an aureole around the sun. It is something very tender and yet very strong. What do I perceive with my light-skin? “Tender” is much more than just the opposite of hard or strong. Tenderness has the potential for self-awareness and world awareness – something we may need in the future. That’s why it seems valuable to me to research its essence and bring it into cultural life.

What in yourself or in the world do you use as a medium to explore tenderness?

On one hand, there are concrete psychological experiences – my own emotional experiences and those in the stories of others; on the other hand, there are my judgments about who or what appears tender and why. How other people explore this theme varies. One artist in our “Pink and the Rest of the World” group bought a pink dress to find out how it made her feel. When you start talking about exploring tenderness, people look for things through which they have experiences. For example, I have noticed that when I hurt someone, the realm of shame opens up. There is a kind of vulnerability or tenderness in that. Is shame a sister of tenderness, a precursor to tenderness? Here, too, I need my light-skin because I have to remain transparent without completely losing myself in something.

When you are hurtful, can you see your own tenderness?

Not at the moment, I think, but I’ll have to look closer at that. I hurt someone else because I feel threatened, hurt, and exposed myself. In hindsight, I can see that “shooting at the other person” comes from a wound of my own, something we all probably have.

Everyone knows how it is to hurt and to be hurt. Shame can come from either one. Today, I’m starting to understand that there is something tender in panic, restlessness, dissatisfaction, or hurt that has not yet found its power. It is a tenderness that does not express itself confidently and creatively, as in artistic work. It can be obscure and destructive. Does this fragility or frailty of tender things have to do with pain for you?

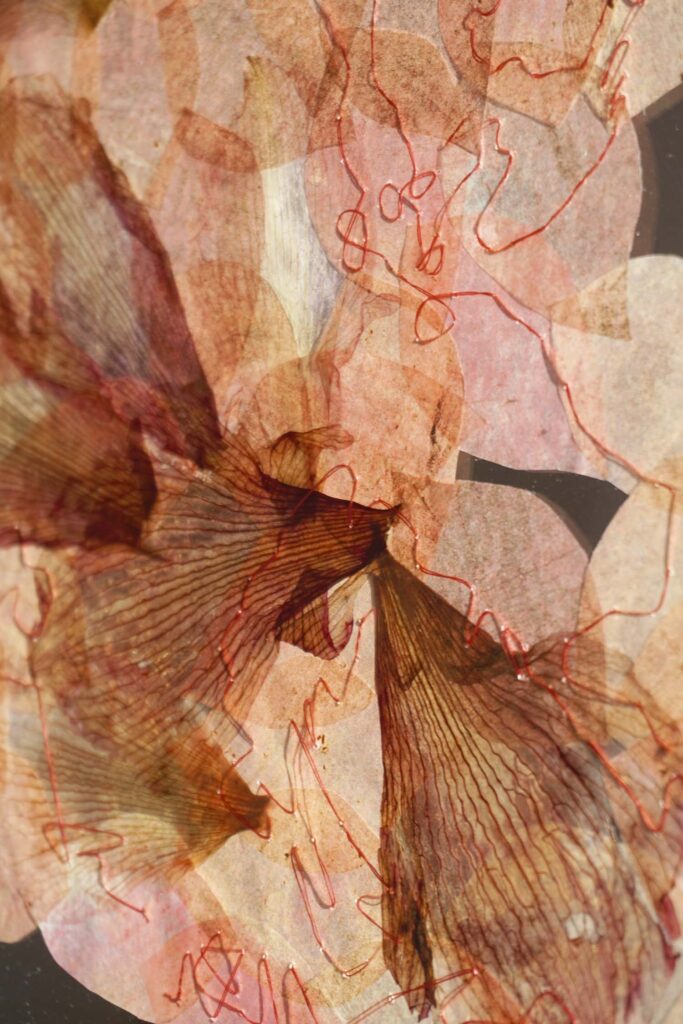

I wouldn’t say that. Not always. Tender things are quickly broken. That is not necessarily painful, but rather expresses a quality. You need to be careful when dealing with them. For example, in my current work on the theme, I use delicate dried flowers, which I fix and sew lines onto with needle and thread. I have to work extremely carefully. I’m also interested in the fact that if it hangs somewhere later as an object, it will simply get broken and disintegrate. That’s part of the work. I don’t find that painful.

I ask because tenderness has often appeared in the same breath as vulnerability or fragility. Does tenderness also have a strong, powerful, pleasurable side for you?

There is something like “tender pleasure” that doesn’t really want to understand itself, is innocent, and still knows how to enjoy itself – like an exhalation that smiles. Its strength lies in its quality: you feel, half-consciously, at home within yourself and in the world, without slipping into egotism. It’s full of life, because the gentler currents can be heard. Perhaps it is most closely comparable to joy, as opposed to fun, and is somehow in the right balance and beautiful.

We picked up this topic at Eastertime because it seems to me that your research has to do with the Easter event. Spring has this quality anyway. For me, the image of the crucified man is infinitely tender, not just tragic. It also depends on the way it is presented. The sight of Jesus Christ on the cross opens me up, makes me tender, or reminds me of being human. Is the Easter experience associated with tenderness for you, and if so, how?

That’s a very beautiful question: the fact that it expresses, as you say, something “human” that is so tender that we find it difficult to grasp without breaking it. It is a tenderness that we experience when we are “feeling true” [Wahrfühlen], not just perceiving [Wahrnehmen], and which at the same time is itself something tender. I experience a second tender quality of Good Friday and the Resurrection, in the possibility of new beginnings. Beginning is always tender. This phrase “feeling true” makes it clear to me: tenderness lies in the feeling that there is a potential in humanity that can begin again and again – and being aware of this potency, like a seedling. “The tenderness is what comes through,” a friend said to me recently.

I find “feeling true” to be very appropriate here. I believe there is also a tender thinking and a tender willing. Nevertheless, tenderness, as I’ve observed it, has to do with a quality of feeling. There is also the word “true” in this phrase. Does tenderness lead to truth? Does this mean being authentic, or does being tender and feeling true open up a layer of existence for me that goes beyond my personality? I look at Christ on the cross and feel that someone has given themselves up and made themselves completely vulnerable. There is something in this that shakes me, takes me out of everyday life, and makes me tender. This person on the cross, with all the wounds, has let go of everything that could be of personal interest. In some depictions, I also see this in the face or in the body, which appears to be floating rather than hanging limp and heavy. I find that to be “tender”.

You also told me: “The tender thing saves me; I do not save the tender thing.” That describes this quality. I also experience gentleness in this. Feeling true opens up to a warmth, perhaps for what arises as a spiritual being in its encounter with me.

When someone has been softened [erzartet, a play on Zarte which means tender], gentleness comes into the soul.

Tenderness doesn’t mean having no edges. Tenderness is part of the many and varied characteristics of people and the world. But if tenderness is on the exterior, what is on the interior? In what way does tenderness shape my strength—what direction would it give? This appears golden to me, like the transformation of pink: a quality that supports different things, opens up, doesn’t exclude but includes and connects, like soil on which many things can grow.

So, what can tenderness give us? “Tenderness saves me” is, for me, a gift. It came out of a conflict. I felt inwardly that I don’t seek understanding because I like to be gentle—but because only this wanting to understand or this feeling true allows me to be myself. I remain “tender” for myself, not for someone else. When I safeguard tenderness within me, it saves me and my soul; I safeguard my salvation.

Or perhaps my security, in the uncertainty of vulnerability. Yes, I know that, too. If I build a wall because I’m hurt, then I’m sealing off my soul, and nothing tender or beautiful can get in anymore. In my understanding of it, the Easter event actually makes it possible for me to endure being myself and keep from closing myself off to others or the world. This also isolates me, but at the same time, it connects me. When I endure standing in my vulnerability, when I learn to stand in my pain, it builds a bridge to another. At this point, hurt or vulnerability resonate with the essence of tenderness. In this, I surrender myself; I am fragile and tender.

Christ on the cross is broken. Not in spirit, but externally – a completely battered sight to behold. At the same time, something becomes transparent for me to see.

Can you describe what shines through? You said earlier that it is being human itself.

There are two levels. There are the wounds, the absolute catastrophe. This brings me back to my humility and reminds me that I am tender and fragile as a human being. I’m not invincible. And then there is the fact that in the image, I see someone who has let go and given freely. I am allowed to look at this person in their most humiliating moment. I can actually look at him as a sacrificed person – someone showing me their wounds, their finiteness, but thereby their infiniteness, their transparency.

Do you know this Dostoyevsky quote: “The world wants to be saved through tenderness”?

I don’t know it, but it’s true for me. In the spirit of Easter, I would say, it was saved through tenderness. I’ll end with a quote from the book Radical Tenderness – Why Love is Political [Radikale Zärtlichkeit. Warum Liebe politisch ist]. The author Şeyda Kurt writes: “I am in a crisis. I am in a crisis of truths and presences. It’s messy here. And this disorder will continue. […] Disorder is also the origin of a radical tenderness. […] Disorder makes room for utopias.”1 Do you see tenderness as an opening, a point of reference in what is now known as the “poly-crisis”?

Yes, I can see that. Tenderness is related directly to us and to whether we are able and willing to look at ourselves, even in our woundedness. I think it is a potential path because it cannot be determined by others – we have to each take it by ourselves. Every single person has to navigate it themselves, including what they have not yet mastered. We can’t get rid of this path of tenderness. This is probably the case with all things, but in the case of tenderness and vulnerability, it seems very obvious to me: if I follow the path of tenderness, I can’t rely on anything. I can’t escape. It takes me directly into my own soul, where I have to become transparent to myself, where I also have to learn to be loving with myself. This allows me to be loving with others – permeable and accepting of their differences.

This is where I find the color pink exciting. After the night, it is the first glow of warmth, almost as if it was the birth of light into warmth. In the morning sky, sunlight is like a virgin princess, who then lives a life during the day and sets in the evening as a king, in deep red. I don’t intend this as the view through rose-colored glasses, but this path is only possible for each person individually. It throws me into my failures, into my ignorance, into my own armory that I have to feel, into my shame, but also into my unnamed potential, into the power that makes me begin to understand and nurture a seed. I have to surrender myself to the fact that I myself am as tender as a seedling and don’t yet have any answers. Of course, tenderness is not just pink. All my attempts to try something without knowing where it will lead are also tender. And the interesting question: what happens when I’m tender?

Translation Laura Liska

Image Gilda Bartel, Light-Skin, collage, 2023/24. Dried flowers, pigmented tracing paper, thread.