Marginalia on Rudolf Steiner’s Life and Work No. 22 – The Sister had the works of her famous brother read to her after her blindness. The deaf brother copied them after his death.

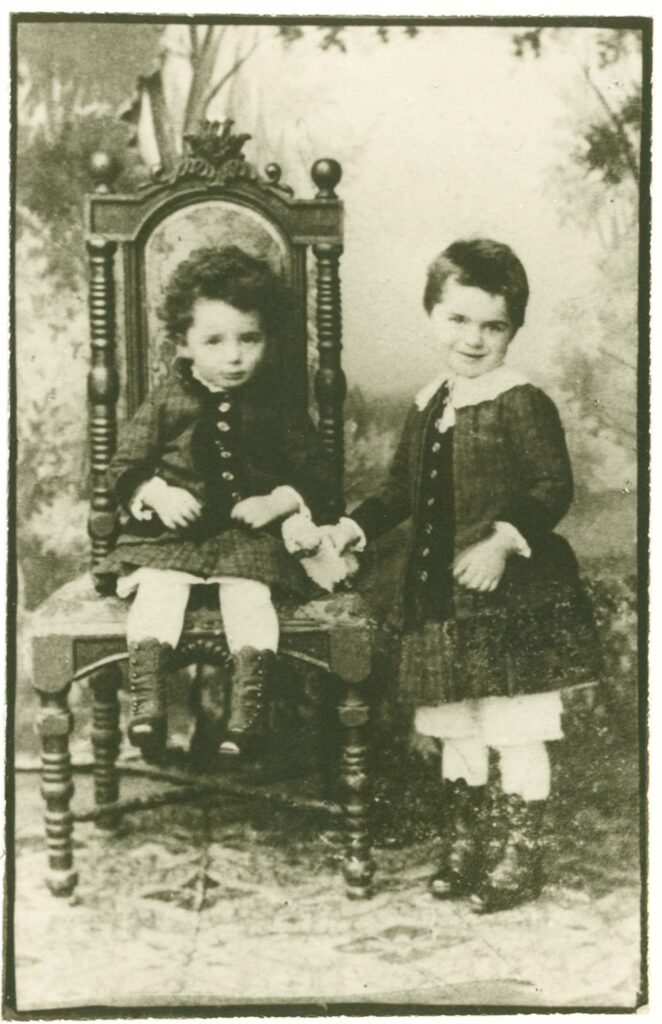

Rudolf Steiner had two younger siblings: Leopoldine and Gustav. Both were born in Pottschach and had godparents from the Solterer family, owners of a mill in the village. 1

As a child, he «often spent hours» looking at picture books with moving figures with his sister, Rudolf Steiner tells in ‹Mein Lebensgang›.2 Leopoldine Steiner herself mentioned to Carlo Septimus Picht that she sometimes came to meet her brother on his way home from school in Wiener Neustadt to help him carry the heavy school folder but also «to support him in the ‹fear of the gypsies›.»3.

The three siblings worked together in their parents’ garden: «Cherry picking, gardening, preparing the potatoes for sowing, tilling the field, digging up the ripe potatoes, all this was taken care of by my siblings and me.» (GA 28, p. 41)

The Sister – Leopoldine Steiner

Leopoldine Steiner (Pottschach, 11/13/1863–11/01/1927, Horn), called Poldi in the family, probably attended the village school in Neudörfl for a few years and then worked – like her mother – as a seamstress until this was no longer possible for her due to her increasing blindness. She stayed with her parents until their death and cared for her brother Gustav for as long as possible. So both of Rudolf Steiner’s siblings never married.

With her cousin Mizzi, Leopoldine was once at a lecture by her brother when he spoke on February 20, 1893, about ‹Uniform conception of nature and limits of knowledge› at the Scientific Club in Vienna.4 A visit to Berlin was also once planned. So she wrote to her brother on April 19, 1902: «Dear Rudolf, I would like to see you, that is if you are so good and really send me a card, visit you for the Pentecost holidays, but if you are planning a trip or anything at all at this time that I might want to come inconveniently, so write to us. Dear Rudolf, but you have to write me about which train and how I have to travel at all and at what time I should leave here, that I arrive in Berlin by day and not by night. So be so good and write me everything in detail, you know I never travel, and that’s why I am a little awkward.»5 Whether this trip really took place, we do not know.

After her father died in 1910, Leopoldine Steiner took on the task of writing to her brother for the family. Given her probably only rudimentary education, how well she could write is impressive. The topics that appear in her letters are similar to those in her father’s correspondence: weather, health conditions, congratulations on the name day, death of relatives, and the request that the brother writes more often or even come to visit. Again and again, she also thanks him for his help: «Dear Rudolf, you are so good to us. If we did not have you, what would it be with us? Only your mother asks you should sometimes write a card, only if you are healthy. We read about so many accidents, and now with this cholera everywhere, we are anxious.» (09/05/1910) – «We have received your mission, and Mother thanks you many times. Dear Rudolf, the mother is always in fear because you send so much that, in the end, it could hurt you in a way. Without your help, we wouldn’t be able to get out of this inflation, but we would be happy with much less.» (09/19/1912)

Once Rudolf Steiner apparently sent a postcard with a view of the emerging Goetheanum. Leopoldine Steiner wrote to him: «The card has also given us great pleasure, that house must be really very beautiful, and we can imagine what the dear Rudolf has for effort and work, but if you only have a little time, write us a few lines again.» (08/15/1914)

From 1916 – due to the war – there was a lot of military in Horn, which led to food shortages in the village: «As far as I am concerned,» writes Leopoldine Steiner in 1917, «I have now become a whole alley girl because you have to walk all day now, that you bring together what you still get to eat and do that for a long time, it’s really terrible sometimes.» (09/08/1917)

In September 1919, the siblings worked together for their famous brother: they wrote a letter to the editor of the magazine ‹Leuchtturm›, Karl Rohm, to reject his out-of-the-air assumptions about Rudolf Steiner’s Jewish origin. «In one of your summer issues, you have printed several claims about Dr. Rudolf Steiner that are quite untrue. Dr. Rudolf Steiner is the son of a Roman Catholic family from the Waldviertel of Lower Austria […].»6 The local pastor even confirmed the statements about the origin of their brother in Horn.

In 1919 Leopoldine’s eyes worsened so that on December 15, 1920, she wrote: «Dear Rudolf, we are both healthy, only my eyes often make me so anxious, I can sew and knit almost nothing anymore. Gustav fell in the room last summer and knocked out a deep wound and a tooth on his chin. Dear Rudolf, it is often so painful to me that we are such a burden to you. You really do a lot for us two poor human children.» On March 31, 1922, she complained: «[…] I want to work so much; the handicrafts are now paid very well, but with my sick eyes, it is quite impossible for me, and I am very desperate about it.» Rudolf Steiner tried to help as far as he could, sending doctors over and her medication.

Since she herself could no longer write due to her blindness, Leopoldine Steiner dictated a letter to Marie Steiner after the death of her brother Rudolf on April 3, 1925. The letter is more upscale in language than her other letters but certainly comes essentially from her: «Revered sister-in-law! I truly do not know with inner melancholy what to write to you in my greatest dismay and excitement! The bad news, which is so completely unexpected to me and so surprising to me like a lightning bolt out of the blue, has shaken me so deeply that I can hardly think properly today!!! […] In mere, dry words, I cannot possibly express my great pain in any way and tell you from the innermost heart what this greatest loss means for Gusti and me and, in any case, in the same way (also) for you, dearest sister-in-law!!! This knows and can truly only be understood to some extent by those who have calmly pronounced this real and truly good and great full and noble man – even as his biological sister; I can pronounce this without committing praise here because it is completely true and right – as you, his beloved wife, will be the best to confirm. […] I, his sister, whom he has also given insight here and there into his superhumanly large and noble world of ideas as far as possible, can remind me of the one that he has often made hints in such a way that man dies physically, but not spiritually, i.e., that he embodies himself everywhere after his physical death somehow and somewhere again. That is why I firmly believe that our beloved brother Rudolf […] has now physically gone home, but in reality, is not dead, so he lives on spiritually among us and continues to lead and guide us all as before.»

«That is why I firmly believe that our beloved brother Rudolf […] has now physically gone home, but in reality is not dead, so he lives on spiritually among us and continues to lead and guide us all as before.»

Later, Leopoldine Steiner listened attentively to her brother’s cycles.7 But she was not to survive him for very long – she died of tuberculosis at 8 a.m. on November 1, 1927, shortly before her 64th birthday.8

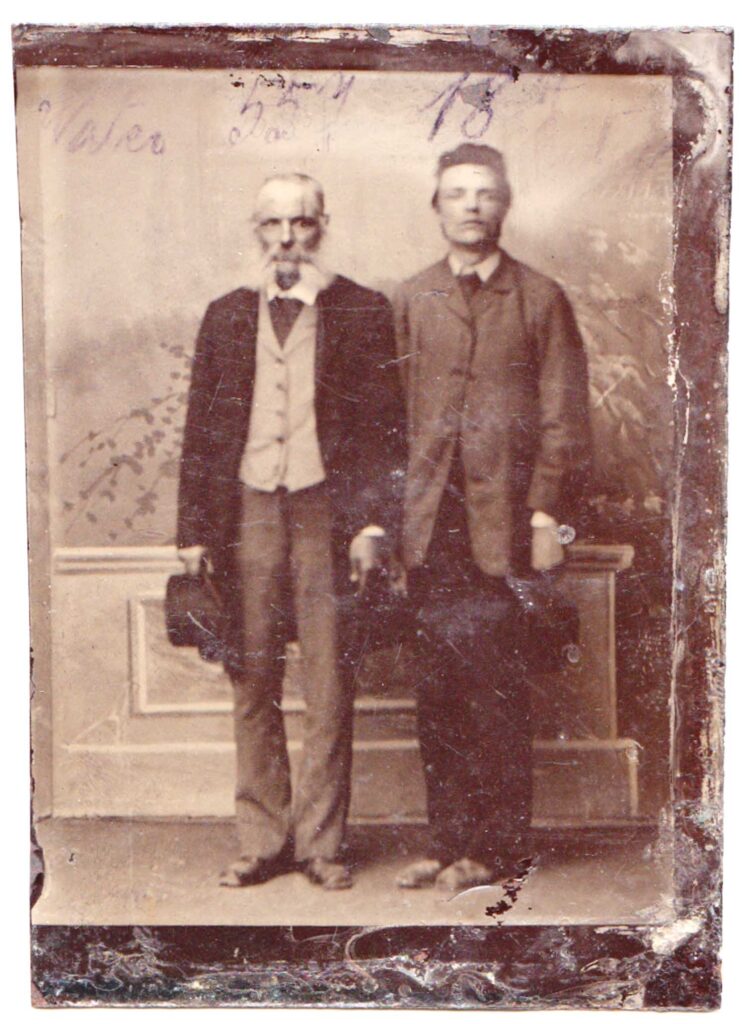

The Brother – Gustav Steiner

Franziska Steiner is said to have suffered a severe shock from a railway accident shortly before the birth of her son Gustav (Pottschach, 07/28/1866–05/01/1942, Scheibbs).9 The fact that their youngest child was born deaf may be related to this.10

Ludwig Müllner reports from conversations with Anton Gliederer – the son of the landlord of the «Gliederer-Haus» in Brunn am Gebirge, where the family lived from the summer of 1882 – that «the parents had given him[Gustav] in turn to various institutions, where he ‹but did not stay with them› and kept coming back home.»11. Gliederer described Gustav as «mentally not unregistering, friendly, and with a natural wit.»12.

Rudolf Steiner probably tried to teach his brother while still living with the family. This can be inferred from a letter dated July 12, 1915, to Willy Schlüter, which says: «Many years ago I also gave deaf lessons and saw what the lack of the musically effective in the imagination life has for an influence on the psyche.» Rudolf Steiner probably also had the following experience with his brother for the first time, mentioned in the letter: «I had always noticed that I immediately had the trust of a somehow frail or crippled person when I focused on the fact that only the physical body has the infirmity, but that the spiritual form underlying the physical body is fully intact.»13 He probably tried to get Gustav a teacher, as seen from his father’s letter of March 13, 1892: «9 days ago Mr. Wachlin, a deaf-mute teacher, was here, just said that he had spoken to you in Vienna.»14

As seen from the family’s letters, Gustav required constant care and supervision. At times he was very nervous and excited and «caused quite unpleasant behavior as a result» (12/6/1907)15 After the death of his father, his seizures caused difficulties for his mother and sister: «[…] only the Gusti still gets his seizures, a few weeks ago he made us a few times such a riot that the mother and I could not tame him and had to call the housewife for help. You can think like we were embarrassed.» (09/05/1910) – «I would have written to you, dear Rudolf, earlier, but Gustav must not see that I am writing. He thinks that I write something of him, and then he makes riot,» so it says in Leopoldine’s letter of December 1911. «With Gustav, there is always a cross with his nervousness. He must not see that we sew or wash something for him, and for me to be able to write this letter, the mother must go away with him so that he does not see any of it.» (09/19/1912)16 So mother and sister always had to think about how they could take care of him inconspicuously: «If only Gustav were a bit good, but he still doesn’t want to buy anything and have nothing sewn, and says that if he has torn his old clothes, he wants to die.» (03/09/1914)

Gustav Steiner loved to read the newspaper, so Leopoldine always had to provide him with newspapers. The fact that he liked to eat a lot made the sister sorrowful in the times when it was so difficult to get food. He had «always a too great appetite for these times» (04/13/1919). In the letter of November 28, 1919, Gustav personally added a sentence: «Gustav also sends warm greetings.»

When the sister could no longer take care of her brother because of her increasingly deteriorating eyes, a relative, Mrs. Barth, first looked after the siblings. However, Leopoldine Steiner didn’t get along with her. Then the nurse and anthroposophist Margarethe Karner took over the care of the siblings. When she herself fell ill in the 1930s, Gustav Steiner joined the Jahn-Hamburger family in 1936, first in Vienna, then in Gresten near Scheibbs in Lower Austria during the war years.

It is touching that in his later years, he loved copying his brother’s works: the first many prophecies and the soul calendar.

Thanks to Wolfgang Vögele’s initiative to record the memories of the daughter of this family, Gertrud Schmied-Hamburger, we know a lot about Gustav Steiner’s last years. Gertrud Schmied-Hamburger reports that he was able to speak a few words, but «of course, he spoke to us in sign language»17. When Gustav wanted something from someone, he tried to make himself understood with a kind of beep. He was «not shy of people at all» but approached all people and asked them about their name days. 18 He was «actually of robust health. He was loving and very happy to help, as far as he could help […]. He got us wood […]. He did a great job of that. He also untied strings and picked seeds. He was always helpful. He never freaked out.»19 Obviously, his agitated nervousness, which is often reported in the family’s letters, had subsided in the later years of his life.

It is touching that in his later years, he loved to copy the works of his brother: first many prophecies and the soul calendar, then followed by ‹How do you gain knowledge of the higher worlds?› and ‹Theosophy›. As Hede Hamburger reported to Johanna Mücke on June 23, 1937, this copying work was «by itself the most important» to him.20.

At the end of April 1942, Gustav probably had a kind of intestinal obstruction and had to be admitted to the clinic in Scheibbs, where apparently no medical measures were applied. Gustav Steiner died of heart failure there on the first night after his admission. – Translation: Monika Werner

Footnotes

- The miller’s wife, Franziska Solterer, was Gustav’s godmother, her daughter Theresie godmother to Leopoldine.

- Mein Lebensgang [1923–1925], GA 28, 9. Ed. Dornach 2000, p. 12.

- Carlo Septimus Picht, ‹Aus der Schulzeit Rudolf Steiners› (From Rudolf Steiner’s school days). In: On Rudolf Steiner’s education, IV. Jg. 1930/31, p. 255.

- This is evidenced by Rudolf Steiner’s Letter to Parents and Siblings of 02/18/1893 (in: Letters Volume II: 1890–1925, GA 39, 2nd ed. Dornach 1987, p. 172).

- All letters of the Steiner family can be found in the Rudolf Steiner Archive (RSA 089). The original spelling was left untouched. Only punctuation was inserted for better comprehensibility.

- The process is described in detail in: Anthroposophy and its opponents, GA 255b, Dornach 2003, pp. 488–492.

- Letter from Antonie Körner to Mrs van Leer, 10/12/1926, RSA.

- So, according to the death register Horn, in which otherwise some things are incorrectly documented, so her year of birth (as 1864). «Widow (?)» is also behind her name and «Everything else unknown.» The heading «Sacraments of Death» says: «Not provided.»

- According to an oral tradition by Wilhelmine Eunike. – On the effects of fear and shock in pregnancy, see the lecture of 12/30/1922, GA 348. It is also possible that this event involves the entrance of a burning railway car to the Pottschach station, which Rudolf Steiner describes in ‹Mein Lebensgang› (GA 28, p. 16).

- Wolfgang Vögele researched Gustav Steiner extensively and interviewed the family’s daughter, where he spent his last years. See ‹Soul Care›, No. 3/2012.

- Ludwig Müllner, Rudolf Steiner and Brunn am Gebirge. Unknown from his youth. Brunn am Gebirge 1968, p. 25.

- Ibid. Kurt Berthold (‹Communications from anthroposophical work in Germany›, No. 143, Stuttgart 1983, p. 31) mentions in his article ‹In the footsteps of the Steiner family in Horn› without citing the source that Rudolf Steiner «himself mastered the language of the deaf.»

- In: GA 39 (see Note 4), p. 646. In Rudolf Steiner’s library, fragments of a booklet from this period have been preserved – ‹The deaf-mute and his education› by J. D. Heil, Hildburghausen, 2. Ed. 1870, RSB Pä 28a.

- Rudolf Steiner had been in Vienna for about a week at the end of February 1892.

- Similar in the letters of 12/14/1909 and 12/08/1910.

- Similarly in the letters of 9/27/1913 and an undated letter of 1914.

- Vögele 2011, see note. 10, p. 24.

- The name days played a significant role in the Steiner family, as the mutual congratulations on these testify.

- See note. 17, p. 25.

- See note. 17, p. 27.

Thank you!