His father fought for his children and was a freethinker. His quiet mother feared throughout her life that her son was overexerting himself because of the financial support he kept sending home. It was a poor but loving home.

Rudolf Steiner came from a family that lived in modest circumstances. His parents, he relates, had «always shown a willingness to give their last penny for the good of their children; but there were not very many such last pennies available.»1 His father, as a kind of minor employee, a private official at the non-state Austrian Southern Railway, always had to fight «poor pay» and had only a meagre income,2 so that some things were unaffordable. Honey, for example, was «already so expensive […] that with the poverty of my parents we were simply not able to buy any honey».3.

His father and mother were «real children» of the Waldviertel, «the beautiful Lower Austrian woodland north of the Danube.» «My parents loved what they had experienced in their homeland. And when they spoke of it, you instinctively felt how they had not left this homeland with their souls, despite the fact that fate had destined them to go through most of their lives far from it.»4 Once his father had retired, his parents moved back home.

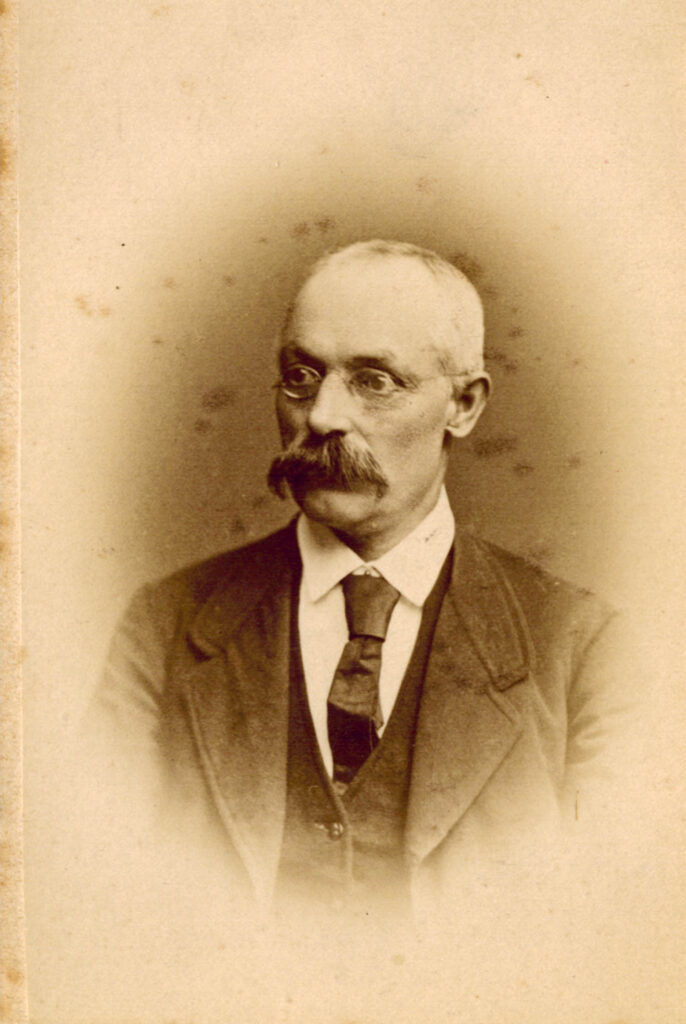

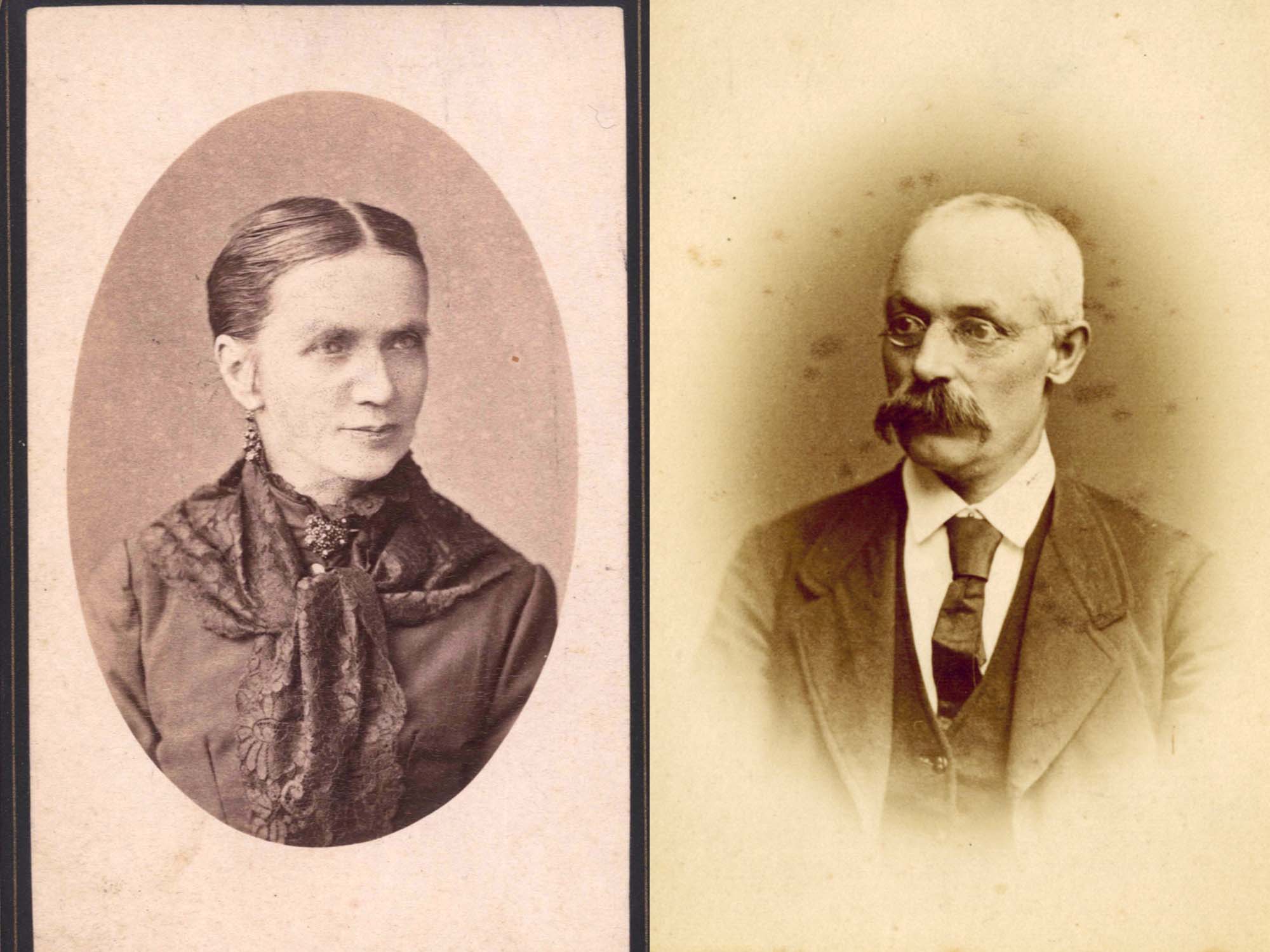

His Father – Johann Baptist Steiner

Johann Baptist Steiner (Trabenreith, 23 June 1829–22 January 1910, Horn) had spent his childhood and youth «in the closest connection with the Premonstratensian monastery in Geras».5«He always looked back on that time of his life with a great fondness. He liked to tell how he had performed services at the monastery and how he had been taught by the monks.»6 The «people at the monastery liked him and even gave him a scholarship to study towards the first classes of grammar school».7 «He subsequently became a gamekeeper in the service of Count Hoyos. This family owned property in Horn. That is where my father met my mother. He then left the game service and joined the Austrian Southern Railway as a telegraph operator. He was first employed at a small railway station in southern Styria [Prestranek]. Then he was transferred to Kraljevec on the Hungarian-Croatian border.»8 The further stations in Johann Steiner’s work were Mödling, Pottschach, Neudörfl, Inzersdorf and finally Brunn am Gebirge; he rose from telegraph operator to cashier and finally became stationmaster.

His father, according to Rudolf Steiner, was «a thoroughly benevolent man, but with a temperament that, especially when he was still young, could flare up passionately. Railway service was his duty; it was not something he loved to do. When I was a boy, he had to be on duty at times for three days and three nights. Then he was relieved for twenty-four hours. So life offered him nothing colourful, only greyness. He enjoyed following the political situation. He took the liveliest interest in it.»9 When Johann Steiner talked politics with a colleague in the «idle evening hours» – at a table under the lime trees where the whole family was gathered, «mother was knitting or crocheting» and the siblings were messing about – the boy took a lively interest, but not in the content, rather in the nature of the conversation: «They were always at odds; if one said ‹yes›, the other replied ‹no›. All this always took place in a fierce spirit, even a spirit of passion, but also in a spirit of good-naturedness, which was a basic trait in my father’s nature.»10 His colleague sided with the Turks during the Russo-Turkish War of 1877/78, his father with the Russians: «[…] because he disliked the Hungarians, he loved in his simple way to think: the Russians, who had ‹shown who was master› to the Hungarians in 1849.» 11

When Rudolf Steiner was once unjustly accused by the teacher’s wife in the Pottschach village school of a transgression that her own son had committed – namely «dipping a wooden chip into all the inkwells in the school and forming circles of ink blots all around them» – his father became «furious»: «And when the teachers came to us again, he terminated their friendship with the greatest clarity and declared: ‹Under no circumstances will my boy be allowed to set foot in your school ever again›.»12 In the following time, Johann Steiner taught little Rudolf himself in the station office, «between the times when the trains were passing».13. But with him, too, the latter «could not really take an interest in what I was supposed to be taught through the lessons. I was interested in what my father wrote. I wanted to copy what he was doing. In the process, I learned many things. But I could not relate to what he had prepared for me to do as part of my education. On the other hand, I grew in a childlike way into everything that was practical activity in life.» Because of the unattractive handwriting that resulted from the boy’s experiments with grit and a pen, his father called him «an incorrigible ‹fluffer›».14

Johann Steiner had very clear ideas about what his eldest’s career should be. He was given «various pieces of advice» regarding his son’s future career; «[…] he likes to hear what others say; but he acts according to what he firmly wants». He had the intention of providing his son «with the right training for ‹employment› on the railway. His ideas finally coalesced into that I should become a railway engineer.»15 So he sent his son to the regional higher vocational school in Wiener Neustadt. Johann Steiner hoped to be able to stay in Neudörfl, which was close by but on Hungarian soil, until his son graduated from school. But hanging over his head was «the sword of Damocles that he could not be stationmaster at Neudörfl station because he could not speak Hungarian», because the «Hungarian government was working towards having the Hungarian lines of the railways staffed with Hungarian-speaking officials even on private railways». Perhaps this was also why he «was not at all happy» with the Hungarians.16.

Johann Steiner was a «freethinker»: «My parents were not pious people at that time. Even in Pottschach, my father always claimed that ‹duties come before worship› and excused the fact that he never went to church by saying that his duties did not give him time to pray.17 He even removed his boy from serving as an altar boy, which he loved, when he was once threatened with a beating for being late: «My father was so incensed at the thought that ‹his son› should have been beaten that he said: ‹That’s it with being an altar boy. I don’t want you to go there ever again.›»18 It was only in old age that his father became a «pious man»19.

Thus Rudolf Steiner found no encouragement at home with regard to his «relationship with the church. My father took no interest in it.»20 When the approximately eight-year-old had a spiritual experience in which his mother’s sister, who had just taken her own life, appeared to him and asked him for help, he made «a few allusions to it in the presence of my father and mother». But they only said: «You’re a silly boy.»21 So the boy «had no one in the family to whom he could have spoken about such things, because he would have had to hear the harshest words about his silly superstition if he had told about this event.22

Rudolf Steiner’s autobiographical account of spiritual experiences on the way to school contains the following sentence: «His relatives were sober people living with the serious cares of everyday life who would not have liked it very much either if the boy had occupied himself with anything spiritual that was of no benefit to life».23 And so it was the railway doctor Carl Hickel from whom the boy «first heard talk of Lessing, Goethe, Schiller»: «In my parents’ home there was never any talk of that. They knew nothing about it.»24

His Father’s Letters

Until Johann Steiner’s death in January 1910, only he wrote the family’s letters to his son. Almost every letter contains the complaint that Rudolf wrote too rarely: «[…] Mum is always quite angry about your letters being so infrequent, because all of us are really very worried when there is no word from you for such a long time.» (13 March 1892)25

In 1899, his father on one occasion wrote indignantly: «Dear Rudolf! That we very rarely and always for an incredibly long time do not hear from you has happened frequently, but that you do not even find it worth the trouble to answer our letters with a few lines, and cannot even completely forget the birthdays of your parents [Translator’s Note: Due to the nature of the German sentence construction in which Johann Steiner sets out to write one thing but loses track of it and completes the sentence with the wrong verb, he inadvertently reverses the meaning of what he intends to say], who are always so concerned about your wellbeing and are close to death, is something we would never have expected; and I ask you [… ] to inform your parents, who are so concerned, by return of post of the cause of your disappearance; if I do not receive any news from you within 10 days, I will be forced to send a letter with rekom Express26 to find at least some comfort in our concern as to whether you are healthy and still alive.» (27 June 1899). Later, when Rudolf Steiner was often on his travels, his worries increased: «[…] it would be very welcome for us if you would send us, if not a letter, at least a card on your continuous journeys, after all, we are very anxious given the many railway accidents which we always read about in the newspapers.» (17 September 1907).

An important topic of the letters were the reciprocal congratulations on name days – Rudolf Steiner apologised explicitly several times when he had missed a feast day: «It is very painful to me that I missed the name day of my beloved father.» (27 May 1895).27 – «I had scruples because I only sent greetings to Poldi two days after the name day. But you must bear in mind that I live here in a totally Protestant country, where people know nothing at all about name days.» (23 December 1895).28 His father wrote to him in 1902: «Our heartfelt congratulations on your coming name day, may heaven grant that you experience many more such days in health and contentment and grant you everything that can make your life pleasant.» (17 April 1902)

Other topics reported in the letters were the state of health, deaths in the village or in the family, as well as the weather – storms, cold, heat, droughts, etc. – and its effect on the harvest and the price of food: «As far as the necessities of life are concerned, everything is enormously expensive here, and there is no prospect of things getting better in this respect either.» (11 April 1907). On one occasion his father inquires with interest: «Do you still not enjoy meat dishes, are you still a vetintarian?» (24 February 1908).

It is remarkable that Rudolf Steiner sent his journal Lucifer–Gnosis to his parents. His father asked him «not to forget to send the following issues» (21 September 1907). And soon afterward he wanted to know «what about the next installment of the journal, don’t forget when it is, and send it to us, I like to read from your work and am already waiting in anticipation.» (6 December 1907). This letter provides unique evidence that Johann Steiner was interested in his son’s literary work.

From Christmas 1909, his father was in pain and confined to bed. He was given the last sacraments on 17 January 1910 and died on 22 January of a «ring-shaped constriction at the stomach exit», which caused «unstoppable vomiting», as the community doctor in Horn, Arnold Hartl, informed Rudolf Steiner in a letter of February 1910.29 Rudolf Steiner wanted to pay the doctor’s bill, but his mother would not hear of it. For Johann Steiner’s gravestone, Rudolf Steiner gave the verse: «His soul rests in Christ’s kingdom. The thoughts of his loved ones are with him.«30

His Mother – Franziska Steiner

Little is known about Franziska Steiner-Blie (Horn, 8 May 1834–24 December 1918, Horn). She worked as a seamstress in her youth. For a time she was «in the service of Count Hoyos» – like her husband-to-be, whom she met there. Since the count made the engaged couple wait a long time for «permission to marry», «they decided to leave home to look for a new life».31.

Rudolf Steiner’s mother must have been a quiet person, as he once mentioned when recounting that he «screamed terribly as a small child» so that «the neighbours were disturbed» and he «always had to be carried around the house»: «Now I will never claim that I learned that from my quiet father and my even quieter mother.»32

«As there was no wealth», Franziska Steiner had to «devote herself to domestic affairs. Loving care of her children and the small household filled her days».33

No letter from mother to son exists, not even a signature. It is possible that she had only rudimentary writing and reading skills, as was often the case in the nineteenth century. She repeatedly has her son admonished to write more often: «Mother is always very angry about the long absence of your letters and always says she will give you a proper piece of her mind when you visit us again.» (24 December 1902).

In view of Rudolf Steiner’s financial contributions to the family, his mother feared, as Leopoldine wrote, that «you are making too great an effort, for the sacrifice you are making for us is really very great» (9 November 1910). His mother was «always anxious because you send so much that you yourself could be hurt in some way in the end» (19 September 1912).

In July 1917 Franziska Steiner became ill: a growth on her foot prevented her from going out. It was not until September that she was able to come along to go to the grave of Rudolf Steiner’s father again. But in November 1918 this painful malady returned, and so on 25 December Leopoldine had to tell her brother by cable: «Mother died suddenly yesterday afternoon.»34 Rudolf Steiner replied immediately: «Shocked to hear the sad news. A journey is not possible at the moment because of insurmountable passport difficulties and other obstacles.»35

Rudolf Steiner’s letters to his family clearly show how closely he felt connected with them – despite his so different inner and outer circumstances. He was «deeply conscious of my duties» towards them and promised to strive «with all my strength»36 to fulfil them. Thus he wrote from Weimar repeatedly that he would like to return to Vienna: «[…] I feel increasingly how much I long to be near you again.» (1 September 1892)37 «Warm greetings and kisses from me, who longs to be with you soon and to be able to show you that I will always be mindful of the duties I have towards you, my dear parents and siblings.” (23 December 1895).38 And as late as 1897 he writes: «You may believe me that I will continue to work with all my strength to come to Vienna.» (3 June 1897).39

As can be seen from the above alone, Rudolf Steiner sent funds to the family as soon as his circumstances to some extent allowed him to do so. The great responsibility he felt for his family members is also evident from his will, in which he ensured that they would continue to receive financial support after his death.40

This article was translated by Christian von Arnim.

Footnotes

- Lecture of 4 February 1913, in: Zur Geschichte der Deutschen Sektion der Theosophischen Gesellschaft 1902–1913, GA 250, Basel 2020.

- See: Mein Lebensgang [1923–1925], GA 28, 9th Edition. Dornach 2000, p. 44.

- Lecture of 5 December 1923, in: Mensch und Welt. Das Wirken des Geistes in der Natur, GA 351.

- Mein Lebensgang, op. cit., p. 8 f.

- Lecture of 8 June 1920, in: Die Anthroposophie und ihre Gegner, GA 255 b.

- Mein Lebensgang, op. cit., p. 8.

- Lecture of 2 March 1920, in: Die Krisis der Gegenwart und der Weg zu gesundem Denken, GA 335.

- Mein Lebensgang, op. cit., p. 8.

- Ibid., p. 9.

- Ibid., p. 28 f.

- Ibid., p. 50.

- Ibid., p. 13.

- Autobiographical lecture, see Note 1, p. 625.

- Mein Lebensgang, op. cit., p. 14.

- Ibid., p. 31.

- Ibid., p. 50.

- In an autobiographical fragment, see: Nachgelassene Abhandlungen und Fragmente 1879–1924, GA 46, Basel 2020, p. 870.

- Ibid., p. 869 f.

- Mein Lebensgang, op. cit., p. 27.

- Ibid.

- Autobiograhical fragment, see Note 17, p. 869.

- Autobiographical lecture, see Note 1, p. 627.

- In: Nachgelassene Abhandlungen und Fragmente 1879–1924, GA 46, Basel 2020, p. 994.

- Mein Lebensgang, op. cit., p. 29.

- All letters are in the Rudolf Steiner Archive (RSA 089). The spelling and grammar of the letters have been left unchanged.

- A type of registered letter where the recipient had to confirm receipt of the letter.

- Briefe Band II: 1890–1925, GA 39, 2nd Edition. Dornach 1987, p. 246.

- Ibid., p. 275.

- In the Horn Register of Deaths, Book 1872–1929, Sign. 04-09, p. 277, marasmus senilis, progressive atrophy of old age, is given as the cause of death.

- In: Mantrische Sprüche. Seelenübungen Volume II, 1903–1925, GA 268, 2nd Edition. Basel 2015, p. 235.

- As reported by Fred Poeppig, Rudolf Steiner, der große Unbekannte. Vienna 1960, p. 14.

- 28 April 1920, in: Fragenbeantwortungen und Interviews, GA 244.

- Mein Lebensgang, op. cit., p. 9.

- The Register of Deaths states that the cause of death was marasmus, i.e. old age, and also that Franziska Steiner could not be administered the sacraments because «death occurred unexpectedly and suddenly» (Horn Register of Deaths, Book 1872-1929, Sign. 04-09, p. 368).

- Briefe Volume II: 1890–1925, GA 39, 2nd Edition. Dornach 1987, p. 476.

- Letter of 10 September 1892; ibid., p. 159.

- Ibid., p. 158.

- Ibid., p. 275.

- Unpublished, intended for: Sämtliche Briefe. Volume 3 (expected to appear in 2023).

- See also: Rudolf Steiner/Marie Steiner-von Sivers: Briefwechsel und Dokumente 1901–1925, GA 262, 3rd Edition. Basel 2014, p. 293 f.

Thank you for the newsletters and the beautiful journals. They are very much appreciated.

Thank you for all the research and work to create this biographical article.