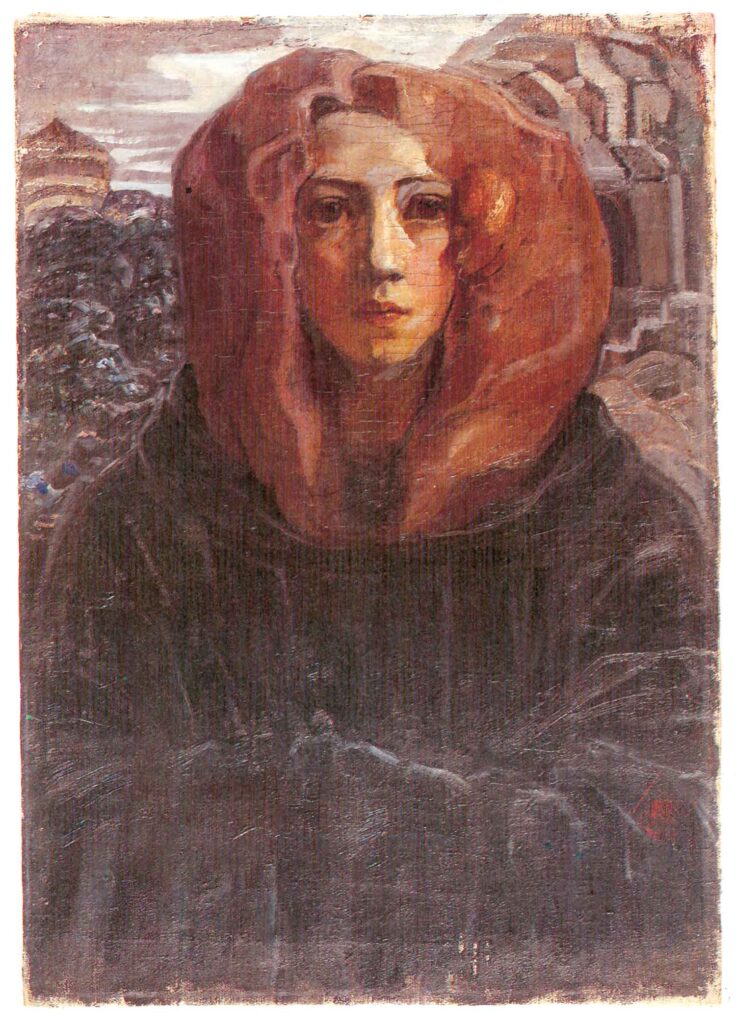

Margarita Woloschina found answers to her questions of life and knowledge in Rudolf Steiner and in anthroposophy. As a painter, she developed a new art in which she sought Christ and completed her work with great seriousness and completely unsentimental.

The Waldorf teacher Ernst Weißert wrote in 1972 on the occasion of the 90th birthday of Margarita Woloschina (1882–1973): «This Russian person, who has been at home in Germany for forty years, lives among us, despite all the familiarity, enigmatic like a secret ambassador of the past and future of Russia, of Central European esotericism, of the radiantly risen Goetheanum, which was so soon snatched from the earth, of Rudolf Steiner’s artistic impulse reaching far into the future.»1

Rich Origin

Margarita Woloschina had a remarkable childhood and youth in ancient Russia, in extremely wealthy circumstances. Her father owned gold mines in Siberia, forests and estates in central Russia, and houses in Moscow. He ran a tea wholesale business with China and traveled with her through the vastness of Russia. The entrance hall of the magnificent house in Moscow, where she grew up, was converted into an Egyptian temple in which the ‹guardian of the threshold› was approached between columns decorated by hieroglyphs. Horse and cart stood in front of the house with the coachman. Two of her father’s brothers owned a famous publishing house, and his cousin Theodor Sabaschnikov was the first in Paris to publish Leonardo da Vinci’s works in facsimile print and had become an honorary citizen of the city of Vinci. Margarita’s mother was the granddaughter of Moscow’s Mayor Koroljew, the first Russian merchant visited by a tsar. Under these circumstances, Margarita received a brilliant education, got to know many languages, history, and art, but also ancient Russia, not least through the numerous servants, including the nannies: «They sewed and sang, individually or in choir, monotonous, melancholic folk songs, and the words of these songs created in my soul a world of archetypes, from which I drew the mood for my artistic work throughout my life. […] There is a Russian proverb: ‹Nourish how the Earth nourishes, teach as the Earth teaches, love as the Earth loves.› When I later heard the word ‹Mother Earth›, I saw a face in front of me that was similar to my nurse Feklusha.”2 Margarita experienced Russian Christianity, the prayers in front of the icon in the morning and in the evening, the unforgettable Easter. From the age of 10 to 13 she was with her mother, brother Aljoscha, tutors and servants in other European countries, in the Swiss mountains, in France, Italy, Belgium, the Netherlands, and in Germany. She met Memling in Bruges and Rembrandt in Amsterdam, Leonardo’s Last Supper in Milan, Raphael in Florence – she, who had an extraordinary capacity for acceptance and experience, for art and nature, sensitive and spiritually gifted. She copied paintings in the museums, attended an art school in Paris for months, had great teachers in the art of painting after her return to Moscow, including Ilya Repin in Petersburg. But Tolstoy, from whom she sought advice for her path in art, disappointed her; a craftswoman or farmer’s wife, as he said, who paints in the evening for recreation, she did not want to and could not become. It wasn’t all easy. The misery of the declassified classes had not escaped her as a child («I felt responsible for all the suffering in the world.») 3); In a youthful way, she experienced the devastating power of the materialistic view of the world and human beings. Then she found Plato, the Bhagavad Gita, and Vladimir Solovyov’s ‹Justification of the good› – and loved the objectively spiritual in mathematics. She achieved great success with her first paintings, finally went to Paris and freed herself from her family, worked in studios, and, together with her future husband, the painter and poet Max Woloschin, met great artists, including philosophers such as Bergson. Nevertheless, she continued to ask about the meaning of art and its relationship to life.

Nobody wants to think for themself

In Zurich, where she had come to in 1905, she heard a lecture by Rudolf Steiner, at the age of 23. «For the first time, I heard about a path to the knowledge of the higher worlds corresponding to our time. I looked up close at Rudolf Steiner’s profile, heard his warm, enthusiastic voice, and took every word like good news. Is it really possible that there is a knower, a real messenger of the spirit in our time?»4 In the fall of 1905, through the mediation of Anna Minslova, she was able to take part in Rudolf Steiner’s internal training course in Berlin (‹Grundelemente der Esoterik› (Basic Elements of Esotericism), met Mathilde Scholl, Eugenie von Bredow, Eliza von Moltke, Sophie Stinde, Countess Pauline von Kalckreuth, and Marie von Sivers. «He spoke about the spiritual precursors of the Earth and human beings. I often wondered by what capacity in ourselves we could follow these descriptions at all, since those states of the Earth, those levels of consciousness of human beings were so little similar to ours. I had to wonder that there are still pictures, still words in our language to describe them. Was one addressed by these descriptions because something of those past worlds had remained in us and around us and was only lifted into the light of consciousness by the word, something primordial, innate? Man himself, connected to the universe from the primordial beginning and only gradually detaching himself from it, is he not to be deciphered as a hieroglyph into which the whole world is secreted? Is it not a fruit of the past, in which at the same time the core of the future lies? I realized that I was not a random guest on Earth, but a co-responsible person who could become a helper in the act of salvation. The myths in which I have lived since my childhood have now turned out to be an essential reality.»5 In the following years, although she often traveled back and forth between Russia and Paris, she attended many of Rudolf Steiner’s great courses, in Berlin and Hamburg, Paris, Oslo, Helsingfors, Nuremberg, Kassel, and Munich. She did not understand everything by any means: «As Steiner already then spoke about the coming catastrophes, about the war of all against all, about the fission of the atoms and the resulting annihilation, I listened to him completely uncomprehending – what kind of catastrophes could come in our so firmly established, humane culture?»6 She had many one-on-one conversations with him about the inner training path and the art, the history, the present, and the future. «I don’t want to press you, but I want to help you like an older brother.»7 Again and again, he gave her exercises and took her inner path tremendously seriously. «The great warmth that emanated from it acted like an invigorating force on me.» She told him about a spiritual experience of nature in Russia and asked him about meditative sayings for the course of time and year. He promised her the sayings («… that he would give them later and that he understood very well what I wanted», April 21, 19098); at Easter 1913, four years later, he showed her the recently published ‹Seelenkalender› (Soul Calendar) in Helsingfors.

She did not always feel comfortable in the circles of anthroposophists. The circle of followers surprised her, also in Hamburg, during the course on the Gospel of John. «The men seemed pedantic and philistine to me and the women prosaic and at the same time sentimental. In ancient times, it was probably other people who followed a spiritual messenger?»9 She also told Steiner again and again about her doubts, about herself and about others. «‹I have witnessed some parts of the Russian church service too real to doubt their truth. […] In Russia, you are serious and simple in church, here, everyone is sentimental and sweet.› ‹Sweet?› – He started laughing. ‹But there is nothing in me that would evoke sentimentality.› ‹Not in you, but everything is projected in the opposite way to what you want. You want freedom and thought, and the opposite arises; here your authority prevails and no one wants to think for themself.› ‹Yes, but I want nothing else than freedom, that depends on the people themselves.› ‹Is there no danger that the sublime words lose their power, for example, the names of the hierarchies, if they are repeated more often?› ‹But I do not say them in vain.› ‹I mean the other people.› ‹That is their tactlessness then.› ‹But you give these words, and you can’t ask people what they don’t have in them.› ‹That will pass. In 2000 years it will be different.›»10 Such conversations did not only take place once – not many people talked to Rudolf Steiner in this way; few had Woloschina’s stature, her spirit, her sense of quality and level, her spiritual tact, and her directness in dealing with him. She was saddened that he had Schuré’s plays staged: « ‹What he writes is a rough illustration, but not art.› ‹It would be wrong to think that if I had his stuff performed, it would also mean that I liked it. But there is nothing else at the moment, and people need it. To you, it seems unsympathetic that I do this?› I couldn’t see it. ‹Yes, you see, if I were of a tranquil nature like you, I would not have spoken otherwise. I understand you very well – but I have to act.›»11

«There were probably not very many at that time who, like her, fully understood what he meant and what he wanted,» wrote Rosemarie Wermbter, who knew Margarita Woloschina like few others and took care of her work.12 Also with life at the Goetheanum in the years of the war, it was for ‹Miss Sabashnikov›, as Rudolf Steiner called her by her maiden name («intentionally», as he told her), not always easy. «I found our life in Dornach, closed off from the world, to be sectarian and averse to life. Apart from Michael Bauer, who else was interested in the cultural phenomena of the modern world? Who would want to deal independently with the phenomena of this world? We knew everything before we experienced it. There was always a quote from Rudolf Steiner between us and being. Didn’t Rudolf Steiner intend the opposite? Didn’t I have to gain my own experiences?»13

He talked to her a lot about spiritual Russia, the importance of anthroposophy for the future of Eastern Europe, and also about Tolstoy, Dostoyevsky, and Solovyov. «He stands in a penitential shirt before Christ for all humanity,» he once told her about Dostoevsky.14 Among important anthroposophists, she was sometimes uncomfortable, although not around Michael Bauer, who became a friend of hers and accompanied her inwardly even in times of need, such as in Russia from 1917 to 1922.15 She once wrote about Felix Peipers and the architects Schmidt-Curtius and Ernst Uehli that they were «solemn, tall, serious people» who dedicated their lives to the service of Dr. Steiner’s work. «Her words are thorough and factual, the jokes cumbersome. You can feel such solidity, such seriousness in everything. You can rely on such people. But – how bored am I with them! Have I been poisoned forever by those brilliant Russian scoundrels? I learn, learn from the Germans, but sometimes the heart grasps such a longing for Russia. But it is doomed, this insane, pathless Russia! No, it’s not true: it’s Ivanushka, the dumb one, where the beautiful ring is wrapped in a dirty rag, but the ring has it …» (March 8, 1912)16 About the endangered development of the Russian soul, in all its longing and talent, she heard from Rudolf Steiner in detail in Helsingfors, where he also held the Easter meal with her and other Russians (in the course ‹The spiritual beings in the celestial bodies and kingdoms of nature›). «You shall, my dear […] friends, experience the spiritual through the soul. You shall find the soul to the spirit. You know it because the Russian people’s soul has immeasurable depths and possibilities for the future.»17

Christian Art

At the actual center of the encounter, however, were her questions about art, eurythmy, mystery dramas, sculpture, and painting.18 She loved the emerging Goetheanum building, in which she was involved – and Max Woloschin was also able to come to him in the days of the outbreak of war after Margarita had written to him how essential the construction and work on it was («Since the days of Hieram there has been nothing comparable.»)19) «Ms. Sabashnikov, can you settle into these forms?» Rudolf Steiner asked her. 20 She carved and painted on the small dome – Steiner left her Egyptian initiates as the only work when he redesigned the entire small dome at the request of the artists. «Christ must be sought today in all areas, including in paintings», was his last word to her. 21 She pursued this in tireless work in the almost five decades that remained after his death. «Christ wants to reveal himself today, that is his essence. The light shines into the darkness, and the colors, his revelation, his language are created. And if you speak this language, if you handle the colors with the feeling of reality, with the feeling that He is there, then this is already a Christian painting, then no further content is needed.»22

Footnotes

- Ernst Weißert, in: Rosemarie Wermbter (Hg.), Margarita Woloschina. Life and work. Stuttgart 1982, p. 5.

- Margarita Woloschina, The green snake. Memoirs. Stuttgart 7, 1997, p. 18 f.

- Ibid., p. 93.

- Ibid., p. 153.

- Ibid., p. 157.

- Ibid., p. I58.

- Ibid., p. 199.

- Margarita Woloschina, From diary entries. In: Erika Beltle, Kurt Vierl (Hg.), Erinnerungen an Rudolf Steiner (Memories of Rudolf Steiner). 1st Edition. Stuttgart 1979, p. 55.

- See N0. 2, p. 199 f.

- See No. 8, p. 55 f.

- See No. 8, p. 57 f.

- Rosemarie Wermbter (Hg.), Margarita Woloschina. Life and work. P. 135.

- See No. 2, p. 301 f.

- See No. 2, p. 203.

- Cf. Peter Selg, Michael Bauer. A colleague of Rudolf Steiner. Dornach 22021, p. 95 f.

- See No. 8, p. 59.

- Rudolf Steiner, The connection of human beings with the elementary world. ga 158. 4th Edition. Dornach 1993, p. 205.

- Cf. Peter Stebbing (Hg.), Conversations with Rudolf Steiner about painting. Memories of five pioneers of the new art impulse. Arlesheim 2015, p. 135–161.

- Zit. n. Sergej O. Prokofieff, Rudolf Steiner and the foundation of the new mysteries. Stuttgart 11982, p. 167.

- See No. 8, p. 70.

- See No. 2, p. 379.

- See No. 2, p. 380.