The death of Traute Lafrenz Page on the evening of March 6, 2023, two months before her 104th birthday, was reported in many daily newspapers; radio and TV broadcasts commemorated her, the last survivor of the White Rose student resistance group. Traute’s friends Hans Scholl, Alexander Schmorell, Christoph Probst, and her teacher, philosophy professor Kurt Huber, had been executed in 1943. Hans and Sophie Scholl, Alexander Schmorell, and Christoph Probst did not live to be 25. Traute lived to be more than 100.

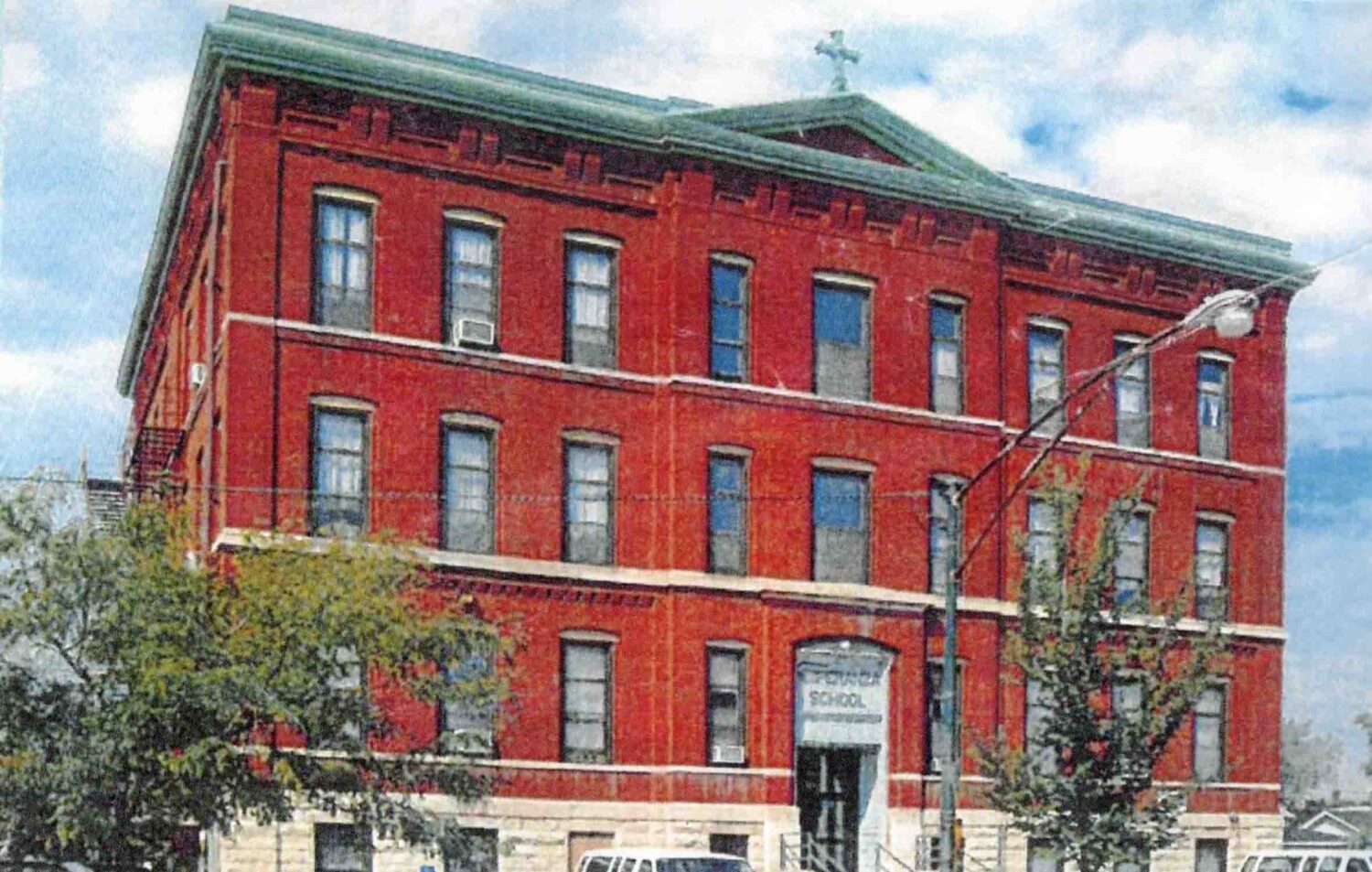

Two years after her release from prison, Traute Lafrenz went to the USA in 1947 at the age of 28, became a doctor there, and worked with her husband, the ophthalmologist Vernon Page, in California and later in Chicago. Then she started working in a special needs day school for children and adolescents in need of special care from very poor families of Latin American immigrants. The school was founded in 1969: Esperanza – a school where ‹hope› is an active part of education. Traute first worked there as a Therapeutic Eurythmist, then increasingly as a doctor. She also employed Rhythmical Massage and eventually led the large school (up to 100 children) surrounded by her team. «It was such a joyful moving time.» «So many kind people of good will.»

If she did not know what to do next in a social situation in Esperanza, she sometimes went to the cook, who came from a poor background and had eleven children. «Ann, what do you think would be a good thing to do?» Traute was the sovereign centre of the place, which was funded by the Chicago authorities and also put on a considerable cultural programme with an Anthroposophical orientation. She also saw herself as a learner: «Sometimes, when I was trying very hard to do Therapeutic Eurythmy with one of the children in Esperanza – it might happen that one of these little people would look at me as if to say: Why are you wearing yourself out like that? After all, I know exactly what lives in the IAO and what it actually is.» (Letter dated October 9, 2014) A Waldorf school did not yet exist in Chicago at that time, in the early 1960s; Traute began intensive summer school courses over six weeks in the suburb of Evanston, where she was also living.

Visit to Buchenbach and Arlesheim

In 1952/53 she came to Buchenbach with two children to deepen her knowledge of Anthroposophic Medicine and studied with Friedrich Husemann and his doctors (Vernon Page was a doctor in the Korean War at the time); In 1960, with four children by then, she came for another year of medical, Therapeutic Eurythmy and special needs education training, this time to Arlesheim, to the Sonnenhof and Ita Wegman’s hospital. She became friends with Julia Bort, Werner Pache, Julie Wallerstein, and Hellmut Klimm – the outstanding special needs teachers and therapists at Sonnenhof. At that time she also witnessed how Willem Zeylmans van Emmichoven reconnected the Dutch national society with the Goetheanum; they knew each other from the USA and in the evening there was a celebration at the Arlesheim hospital where they talked for a long time.

In the 1970s and 1980s, besides Esperanza, she served on the council of the Anthroposophical Society in the USA; she loved the meetings; the friends came from all parts of this vast country. «You know, in Hamburg I would probably never have gone to the Society in all my life, much too confined.» She held class lessons in Chicago – and in other places by request – until 1993 when, at 74, she stopped: «White-haired people should not represent Anthroposophy.» In 1995, at the request of her husband who had leukemia, they moved to the southern states, to Yonges Island in South Carolina, onto a large estate by the water where their daughter, the doctor Renée Meyer, lived with her family – into a small, cosy wooden house.

Investigating the Crimes

Traute did not know then that she would be given another 28 years. Nor that many of the early themes would return. However, she then helped nursing academic and professor Susan Benedict in her research on the role of nurses and midwives in the Nazi era, including German and Austrian nurses who resisted such as Maria Stromberger in Auschwitz; they investigated the euthanasia crimes and many small, largely unknown resistance groups. Together they visited the memorial sites and various archives at the Israeli Yad Vashem memorial. Traute translated the documents for Susan and they talked a lot.

To be sure, in the preceding decades Traute had never completely given up on the subject of National Socialism and the German genocide, even if in the USA there was for a long time limited interest in the German resistance – and in 1952/53 in Buchenbach and 1960 in Arlesheim, no one asked and no one wanted to know. Traute kept in touch with Inge and Elisabeth Scholl and Otl Eicher, whom she visited regularly in Stuttgart and in Rotis; also with her old teacher Erna Stahl in Hamburg, who had also been imprisoned. In Dornach, she was always the guest of her friend Eve Nägele, Ratnowsky by marriage, who had also been friends with the Scholl family and with Alexander Schmorell.

Wide Awake, Highly Intelligent, and Courageous

I knew Traute since 2005, and from 2006 on we wrote many letters to each other; I visited her often in the USA, in South Carolina, and she came to Arlesheim and Freiburg. Once we had a wonderful day together in New York, after lectures on the ‹Fifth Gospel› to 200 people; we escaped ‹in time› and went to four museums in one day (from the Frick Collection to Modern Art), it was pouring with rain and we laughed a lot. She was 93 at the time. She, who had ended up in South Carolina with its sleepy metropolis of Charleston, loved cities, «like an inspiration». In November 2011, she wrote to me about another visit to New York: «A huge city so full of life and young people, plus full concert halls in the evening, Brahms and Liszt, Lieder and piano concerts. It’s hard to believe, so much zest for life.»

We also talked a lot about the White Rose and she was glad to be able to recount some of the things she did not tell the journalists – starting with Erna Stahl, her beloved teacher at the Lichtwark School («I owe a lot to Erna Stahl, a whole about-turn that also includes an inner existence»), who promoted independent thinking, was a brilliant teacher of literature and art, visited the exhibitions on ‹degenerate art› with her pupils, maintained a reading circle and pointed Traute towards the work of Rudolf Steiner. Traute gave an excellent and precise account of all the events. Later, I read the transcripts of her Gestapo interrogations, which are kept at the Institute of Contemporary History in Munich; it can be seen how she held herself in the interrogations, wide awake, highly intelligent, and courageous. «Weren’t you afraid?», asked ‹Spiegel› reporter Claas Relotius in 2018, who by no means made up everything he wrote about [he resigned from the news magazine in a media scandal for fabricating stories]. «No, never. After all, I knew it was the right thing to do.»

An Experiencing of Hell

She often put her life on the line, not only when transporting the leaflets to Hamburg. It is thanks to her that Hans and Sophie Scholl could be buried; Traute managed to get her friends’ bodies out of the pathology department because of her medical studies and with some money («Bought corpses to bury.» Diary). This made burial in Perlach Forest possible, even if under Gestapo observation. February 18 – the day the Scholl siblings were arrested – and February 22, the day the siblings and Christoph Probst were executed, were difficult for her every year. On February 15, 2013, she wrote to me, almost 94 years old: «And now it really is 70 years. Sometimes it seems like it was yesterday, and it is not always easy for me to put it out of my mind.» On her porch in South Carolina or in letters she told about it, and then put a full stop. «And now enough about my life.»

Some questions, however, preoccupied her to the end, such as the betrayal by her classmate Heinz Kucharski, who handed the whole group over to the police in Hamburg, including Erna Stahl – and the question of morality. She didn’t want to talk about the most terrible things, and I didn’t ask either, such as her experiences in Bergen-Belsen shortly after the liberation of the camp. «It was truly the most terrifying thing I have ever experienced. No residue of being human seemed possible any longer. If you can imagine a cold, frozen hell, that’s what it was.» (September 28, 2010)

She struggled for many years as to where to inwardly place her friend Hans Scholl; the idealisation of the White Rose was not her thing, she knew how young they had all been and thought Hans Scholl’s cockiness foolhardy. But she finally made her peace with everyone and everything, even if it was hard, and remained hard throughout her life. «There was something chivalrous in these young people after all. Although there are no more orders of chivalry, there are no monastic vows either and in the end everyone now has only themselves and their actions to determine. And so forth.» (November 12, 2010)

When I got to know Traute, I asked her to write down her recollections; there were many things that only she knew. She indeed started shortly before her 90th birthday, but soon stopped again. «And now I’ve actually started writing, quite well in my head already – a bit slow on paper. And then once I’m really old – ha ha ha – I’ll give it all to you – because actually, I write as if I wanted to have a conversation with you – without any red or violet room and looking into your eyes. Anyway, that’s what I’ve been thinking – for days.» When she was 101, she wrote to me one morning at five o’clock about a dream in which Hans Scholl had come back; at the very end, she sent me a letter from Werner Scholl from December 1942 – Werner, who, after burying his siblings, was sent back to the Eastern Front at the age of 21 and never returned.

Tolstoy, Stifter and Fontane

Traute inwardly lived with the whole of Anthroposophy, but also with much literature, and knew countless poems by heart, right up to Rilke’s ‹Book of Hours› from the time of her essay on his concept of poverty for the ‹Abitur› school-leaving examination. «‹For poverty is great radiance from within.› There’d be a lot to talk about still.» I sent her pictures of the interior of Château de Muzot, which I was unexpectedly able to visit, and she replied with poems. We did indeed also manage to visit Weimar together, the houses of Goethe and Schiller, as well as attend a class lesson – it was the 17th – in Steiner House there. «I was just reading in Prokofieff’s Schiller study about the heavenly friendship between Schiller and Goethe. To me, it seems more like a hard-won and spiritually necessary union – like when you drop everything that life otherwise offers you and then, in soaring up, still come to joyful experience. Not easy.» (September 2, 2011)

But she was also perfectly at home with Stifter and Fontane, with Tolstoy or with the latest modernism; she read and thought with passion, crystal clarity, full of verve and life. «The whole of March I then occupied myself with Tolstoy, such a genius – so knowledgeable about people and nature – a soul as wide as the sea. That makes things look a bit poor in our ranks. Perhaps we want too much and can do too little, or rather we can’t want well enough. God knows, the will is our problem.» (21 April 2010)

She could be very serious and very humorous, always quick-witted, thoughtful, and with fire. She had an extraordinary historical horizon and in her old age for weeks and months studied seemingly the most remote periods and figures with specific questions («And then you realise how big you have to think if you want to think about history – and the development of human existence. ‹How small is that with which we wrestle – / What wrestles with us – how great it is›. Rilke»)

The fact that Anthroposophy did not feature in reports about her did not bother Traute; she herself never made a secret of the importance of Steiner and Anthroposophical spiritual science for her life. «I am a convinced Anthroposophist and I think that to the best of your knowledge and conscience you must live in a way that corresponds to your own convictions», she told Sibylle Bassler in an interview. She also spoke very openly about everything with the film director Katrin Seybold, who meant a lot to her.

Actions Count

Traute’s gift or skilled ability to reliably appraise people, combined with mildness and tolerance, was unparalleled. «That’s just the way it is; volumes could be written about the complexity of the human soul – if you’re smart, it’s better to keep quiet», she once wrote, and in another letter: «That’s just the way it is with us humans – and then you need so much love in this world to be able to see and bear it.» After a family reunion at 96, she said: «There are family reunions where you recognise the real core of the other, love it – guard it because it never quite comes to fruition in one life – and you push everything else aside with a lot of humour and laughter.» (May 8, 2015) Indeed, she could and did, with «a lot of humour and laughter», and a luminously bright intelligence.

The mystery of the human being and the practical knowledge of the human being – including Anthroposophic Medicine – interested her to the very end and she never stopped studying them. «Renée is about to ‹publish› some treatments for patients! Not easy if you want to unify all that with modern knowledge and spiritual scientific knowledge. Prescribe charcoal quite harmlessly and you bring the whole of earth evolution and human development to consciousness. Who can keep that up day in, day out? But let’s talk about something else.» This was in a letter of January 2016, which then moved on to Napoleon and Tsar Alexander I. … She took note of the fact that wars and evil continue to run their course, even after the twentieth century, and reacted with great sorrow. It was not easy for her no longer to be able to intervene in unwelcome developments on a greater or lesser scale. She wanted to act and not just watch, but was restricted in the last quarter of her life – and largely confined to inner work. After reading a lot of Hölderlin and Hegel, she wrote to me: «What goes through my mind is that in the future, actions will count – acts of will, not words. Just like Josef Schulz, a soldier in the German army, who simply refused to comply when they lined up innocent villagers against a stack of hay in a village in Yugoslavia to shoot them – he took off his helmet and went to stand alongside the villagers to be shot as well.» It was on the 20th of July 1941, and Schulz was a young soldier in the 714th Infantry Division.

Inspired by Friendship

When you reach the age of almost 104, you have lost and said goodbye to all your friends, have experienced and suffered illness – yet she was always empathetic and forgot no one. Traute was inspired by a genius of friendship, completely unsentimental and concrete; she remained faithful to people. With her sick friend Lucia from Montevideo, she undertook a long sea voyage, even in her old age; they read works by Rudolf Steiner, were on deck and together. «Terrible – you always wonder about the harshness and near cruelty with which life just goes on … Such an inward, dear person», she wrote in response to the news of Sergei O Prokofieff’s illness (May 21, 2011).

She was of outstanding calibre, conversed brilliantly with Countess Marion Dönhoff for three days, held Freya von Moltke in high esteem – and remained completely modest and unassuming, yet very elegant. She did not want to go to the Leipzig Book Fair, where her biography was being presented. «The embarrassment of being celebrated like this for nothing, absolutely nothing. Simply because you were there at the time – you were present – and were just the way you happen to be. So I think not.» (January 9, 2012) «Well, and all the fuss about the White Rose … is actually also simply embarrassing – because it was just completely different from the way these newspaper people want it to be, ‹The Earthly Remains› – they are all after the earthly remains – bearing your ‹I› – and at the same time everything is at a so much deeper level.» (October 24, 2018)

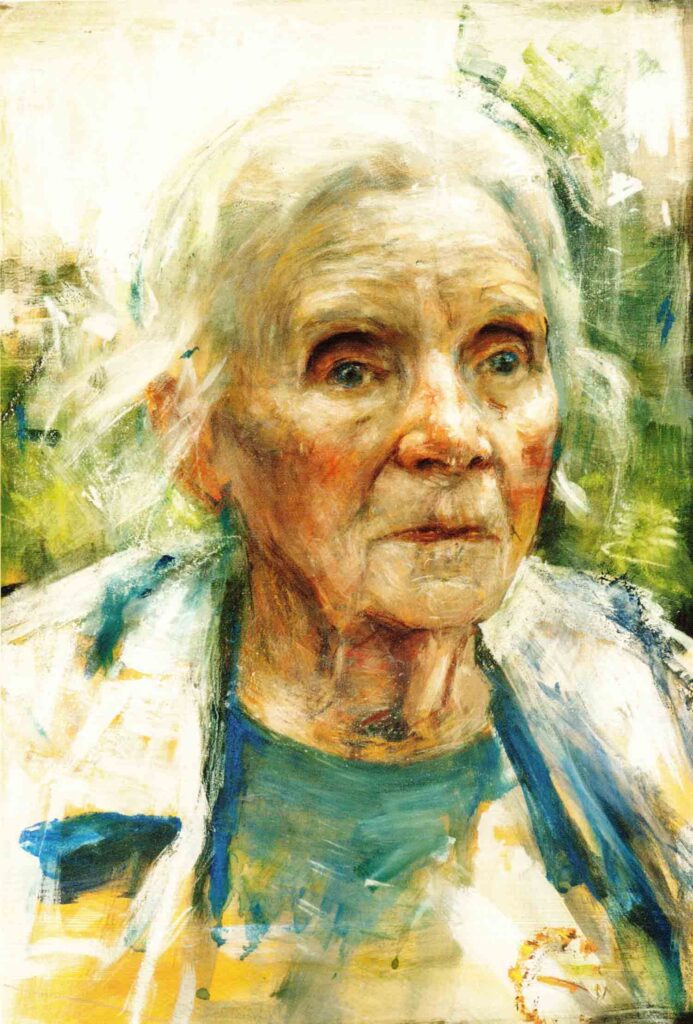

Nevertheless, she sometimes accepted honours and awards, out of courtesy and on behalf of the unknown others who were also in the resistance, as she once said in Hamburg. Vebjørn Sand painted her in 2013 under her huge trees in Yonges Island (‹Angel Oak Trees›) and she went to his gallery in New York («I did my best to keep up with this lively, young lady of the age of 93. Traute is like a light. She is warm, wise, rich and yet curious and challenging at the same time.» Sand)

Yearning for Europe

When she was around 90 years old, she considered moving to Europe and the vicinity of the Goetheanum again before deciding against it in the end, not least because of the family. At the age of 97, in May 2016, she sent a postcard from the cloisters of Saint-Pierre Abbey in Moissac and wrote: «I love these cloisters! If I allow myself to have a yearning for Europe – it’s those cloisters in the south of France and Spain.» There, in the south of France, she often attended classical music festivals, together with Lucia, her Anthroposophical friend.

Despite all the difficulties in its history and the various struggles, she always remained attached to the Goetheanum and its School of Spiritual Science. Here, too, she looked to the best forces and efforts of people; that much of it was not of the calibre that she, Traute Lafrenz Page, thought was necessary was clear. But she remained tolerant and fair, generously overlooked some things, and rejoiced in all positive achievements. When something went wrong it never upset her, and she would never have written critical letters – «we actually have a much longer perspective» (July 19, 2007). «The mills of life simply grind slowly and if you want to think of human progress, you have to think in human generations.» (January 9, 2012) She quoted Thanausis, advisor to the Empress Galla Placidia: «Why be sad, an old Gothic rune says: The dead and the unborn feed on every noble sentiment of the living.»

Once a letter said:

Perhaps we need many Goetheanums – one here – one there – one in China: we appear to be in a time when souls want to come together, in the sense of the Morgenstern poem:

Those who wander towards the truth …

For a while we walk

– it seems – in chorus

And then a Goetheanum in the sense that Rudolf Steiner described it in that deeply moving lecture on December 31, 1923, a building that draws each person entering up as if to the spirit. It is such a deeply moving lecture. The audience must have either stayed as if glued to their chairs – or fallen down as soon as they got up.

What she sometimes missed in her old age were the lessons of the First Class in the Therapy House of the Arlesheim hospital, held by Madeleine van Deventer. In general, Traute was of the opinion that what really mattered was the striving for the inner esoteric core of Anthroposophy; here, in this field, much more work and development was needed. She continued to study Anthroposophy, marvelling anew at all sorts of things, at the books, the lecture courses – or at Rudolf Steiner’s commitment after Sophie Stinde’s death: «The amount of love and care he bestowed on everything that approached him was incredibly wide and great. It is hard to believe.» (June 29, 2011) The ‹Philosophy of Freedom› also remained important to her throughout her life, starting from the Munich days of the White Rose. As late as July 2018, 75 years later, at the age of 99, she said: «Am reading a lot; am reading through the ‹Philosophy of Freedom› in wonderful peace. Every sentence so clear – so freshly thought through.» Rudolf Steiner was for her the «most constant» and «best» companion – «sometimes a little excessively ‹demanding›. Then I pretend to be a bit tired and old.» (December 2, 2014)

Thinking and Looking

The last years of her life were naturally not easy. «I’m fine, just gradually reducing,» she informed me at Christmas Eve 2014, not knowing that she still had more than eight years to go. «Don’t worry about me. The fact is just that a long life is connected with great loneliness.» (December 2, 2015) «I sit on the veranda a lot in the evening and wonder. Wonder how it all turned out this way and how different it could have been.» (August 21, 2016) At 98 years old, she described to me swimming the long way along the jetty:

So with me, things actually just keep on going the same way. Always a bit more unsteady in walking and more forgetful with names. At the beginning of November, it was still warm enough to swim and then when I walk along the long jetty I either have to do the Therapeutic Eurythmy exercise ‹left, right; secure – steadfast – secure – steadfast› etc. very firmly, or I recite long poems to arrive safely. Schiller’s ‹Song of the Bell› would take me all the way to the end, only I’m missing too many passages there. ‹The Diver›, ‹The Hostage›, ‹The Cranes of Ibycus› all work well. Goethe also, ‹The Sorcerer’s Apprentice›, ‹Faithful Eckart›, ‹To the Moon› and others. (November 16, 2017)

Almost five years later, in May 2022, after her 102nd birthday, she then wrote:

With me, things just appear to keep on going the same way. Sarah and Thomas gave me a lovely bench – right by the water – and I always sit there and think and look. Wonderful. –

Wonderful, the strong green of the thick leaves – the blue of the water – the sky – and then boats & people.

Sometimes I think: what if R Steiner had had to live so long??

They – we – would have torn him apart and driven him in all directions. Hither and thither. But for me – I mean here in my existence right here – I can only give deep thanks in the way things have transpired.

My gaze is already on the hill in the sunlight,

Rainer Maria Rilke

ahead on the path I had barely begun.

Thus we are grasped by what we couldn’t take hold of,

fully appearing, from afar –

and it transforms us – even if we do not reach it,

into that which we, hardly suspecting it, are;

a signal is blowing – in response to our signal …

However, the headwind is all that we feel.

As the year 2023 approached Passiontide, two days after the anniversary of Ita Wegman’s death, she was finally allowed to set out on the great journey «into that which we, hardly suspecting it, are».

Translation Christian von Arnim

Title image Traute Lafrenz Page, private ownership

A question: would it be possible for people who actually worked with her, at Esperanza and other centers, to either write or be interviewed about how she worked: specific cases, particular patients, concrete experiences? I think it could be fruitful to document some memories and make them part of the history of the development of anthroposophical medicine, curative eurythmy, and of her work with the society in America. These rememberings by co-woekers and colleagues could be inspiring for younger generations, and for future research.

Yes, I think this could be valuable. I worked with her and could help.