One of Rudolf Steiner’s closest friends during his first years of study was Rudolf Ronsperger (Aug. 29, 1863–Oct. 2, 1890),1 the son of the Jewish Viennese master confectioner Felix Ronsperger. Some of Rudolf Steiner’s early letters come from Ronsperger’s estate and give us an intimate look into what he was occupied with during the summer of 1881.2

Like Rudolf Steiner, Rudolf Ronsperger also studied at the Vienna Technical Institute, although he was reluctant, feeling more drawn to literature and preferring to attend a university. For a while, he sought to switch, but did not pursue it vigorously enough. After his father’s suicide in October 1881, he had to abandon his studies altogether and take a job with the Northwest Railway. In the early days, he kept in touch with Rudolf Steiner by letter. Rudolf Ronsperger felt very unhappy in the railroad service; in 1890, at the age of only 27, he took his own life. In his farewell letter to an aunt, he wrote that he did not want “to continue a life that allowed me little true satisfaction and which in the end only afforded me the prospect of a barren, loveless existence by snatching away the being I loved with all the ardor of my soul and body. The stain of our time, blind racial hatred, has also played its part in this.”3

Only ten years later did Rudolf Steiner hear of his friend’s tragic fate, when Ronsperger’s sister, “the wife of an esteemed writer living in Berlin,” transferred the estate to him, which, in addition to poetic productions, also contained a letter written to him by Rudolf Ronsperger in 1886, but never sent, as he “could not find out the address.”4

A Wakeful Life

His sister, Luise Kautsky-Ronsperger (Vienna, Aug. 11, 1864–Dec. 8, 1944, Auschwitz), was the second wife of the well-known Social Democratic politician and Marx expert Karl Kautsky (1854–1938). After finishing Bürgerschule [middle school with vocational focus], she attended high school [Höhere Bildungsschule], which was unusual for a girl at that time. But, following the death of her father and only seventeen years old at the time, she had to run her parents’ confectionery shop. Through a friend of her older brother Rudolf, the actor Viktor Kutschera (1863–1933), she first met the theater painter Hans Kautsky (1864–1937). She became friends with his mother, the well-known Viennese novelist and socialist Minna Kautsky (1837–1912). It was only a few years later that she also met Minna’s older son Karl—and became his wife in 1890. The couple initially lived in Stuttgart, in the neighborhood of their friends, the Bosch family, where their three sons Felix, Karl, and Benedikt were born. In 1897—the same year as Rudolf Steiner—the family moved to Berlin. Here, Luise Kautsky soon became close friends with Rosa Luxemburg, who encouraged her to write. She followed her advice and, from then on, remained active as a publicist. After the murder of her friend Rosa, she published her letters, among other things. Otherwise, she acted as her husband’s secretary and reader, so to speak, but she was also a city councilor in Charlottenburg for a time. In 1920, she visited the Democratic Republic of Georgia for several months with her husband, where Karl Kautsky was greatly admired. She also wrote reports about this trip.

In 1924, feeling increasingly politically isolated in Germany, the Kautsky couple moved back to Vienna, where their children and grandchildren lived. When the National Socialists seized power, Karl Kautsky, who was half-Czech, became a Czech citizen with his wife. The couple left Austria for Prague at the beginning of 1938 but had to flee from there to the Netherlands after the Anschluss [annexation of Austria into the German Reich], where, after only a brief time, Karl Kautsky died of a heart attack. When the German armed forces then also occupied the Netherlands in May 1940, Luise Kautsky was initially “left alone, as the mother of half-barbarian children . . . ; she did not have to wear the star either, but was under police surveillance.”

Shortly after her 80th birthday, “she was, in the end, taken away during a house search.”5 She was deported to the Westerbork concentration camp, from there to Theresienstadt and finally to Auschwitz. She was only about five kilometers [3 miles] away from her son Benedikt, who had been interned in various concentration camps since 1938. Through helpers, Luise Kautsky was able to send her son two small notes with a few lines in the last days of her life. In a letter dated May 26, 1945, Benedikt Kautsky told his brothers about his mother’s death, which was surprisingly gentle under the circumstances: “She died peacefully in her bed . . . after spending six weeks confined in the hospital. The degree of agony she must have endured, already on the transport, then in the gruesome atmosphere of Birkenau [Auschwitz]—the horror of which can only be truly fathomed by those who have breathed this air themselves—must have been appalling. And yet, how much bravery spoke from her words, which she conveyed to me orally and in writing. Brothers, we can be proud to be the sons of this mother!”6 The prisoner doctor Lucie Adelsberger reported: “Even while so physically frail and decrepit, Luise Kautsky had a spiritual flexibility that nearly put us younger ones to shame. The others could take an example from her will to persevere.”7

A Photo for Provisions

Letters from the Christian Community priest Walter Gradenwitz (1898–1960) to Marie Steiner and Werner Teichert reveal a moving connection. Gradenwitz had partly Jewish ancestors, which is why, in 1935, he was asked by the Oberlenker of the Christian Community to “leave the territory of the Reich and work in the Netherlands.”8 After the occupation of the Netherlands, he had to wear the Jewish star—as a Christian priest!—and was only allowed to communicate with Jews. It was in this context that he got to know Luise Kautsky. She was, as he reported to Werner Teichert on March 25, 1948, “a very special woman; one might say a very mature, kind, deeply Christ-permeated personality—her Jewish ancestry and her communist ideals had become something quite external in comparison. When she spoke of Dr. St[einer], she thought of him in his student days (her contact with him when she gave him her brother’s estate must have been very brief or only by letter), and he stood before her in such a way that she could say again and again: ‘What a dear, dear boy he was!’ And, spoken by her, that sounded like a deeply human impression.”

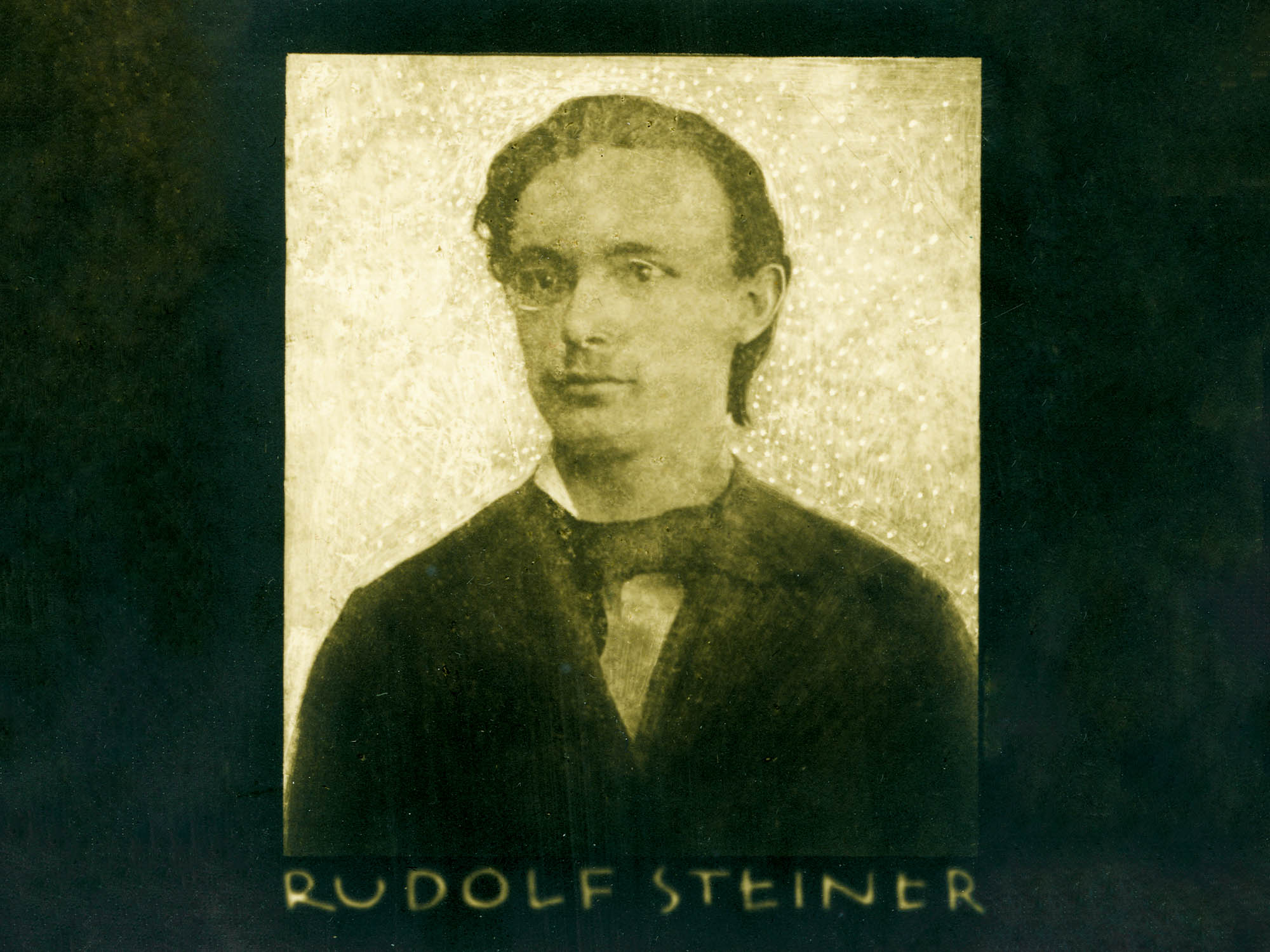

Walter Gradenwitz received a photograph from Luise Kautsky “of Herr Dr. Steiner from the 1880s” in order to have “around 200 prints” made of it. What for? In order “from the proceeds, to be able to send packages of provisions to Jewish members in concentration camps”!9 But the original photograph, “which was in the hands of Mrs. Kautsky, . . . was lost due to her sudden death.”10

This photograph of Rudolf Steiner in his youth was edited by the Viennese photographer, painter, and poet Josef Anton Trčka (1893–1940) in his typical way, for example, by changing the background in the negative with a brush. Trčka and his wife Clara became interested in anthroposophy in 1915. Apparently, Luise Kautsky had given him the original photograph from the 1880s, which was probably still in her brother’s possession, during her later time in Vienna. It is remarkable that she took this photograph of a young Rudolf Steiner with her when she emigrated!

Translation Joshua Kelberman

Footnotes

- A more detailed sketch of Rudolf Ronsperger’s life can be found in my book: Rudolf Steiner, Kindheit und Jugend [Childhood and Youth] (Dornach: Verlag am Goetheanum, 2018), pp. 298–303.

- The letters were in the possession of Karl Kautsky Jr., the second son of Luise Kautsky, who “made his living as a doctor in California.” He made the letters “available to the Goetheanum,” as reported by Friedrich Hiebel in Das Goetheanum 46, no .9 (February 26, 1967).

- Kautsky Papers ARCH00712.1751_4, International Institute of Social History, Amsterdam.

- See Rudolf Steiner’s article “Ein Denkmal” [A Memorial] in: Gesammelte Aufsätze zur Kultur- und Zeitgeschichte [Collected Essays on Cultural and Contemporary History] 1887–1901, GA 31, 3rd ed. (Dornach: Rudolf Steiner Verlag, 1989), p. 364. He was so shocked by Rudolf Ronsperger’s fate, which he also saw as “the understandable consequence of his Austrian character and the . . . circumstances in Austria,” that he composed this literary “memorial” for him. Rudolf Steiner also commemorated his friend in his Autobiography: Chapters in the Course of My Life, 1861–1907, CW 28 (Hudson, NY: SteinerBooks, 2000).

- Letter from Walter Gradenwitz to Werner Teichert, March 25, 1948, Rudolf Steiner Archive, Dornach.

- From the estate of Benedikt Kautsky, Verein für Geschichte der ArbeiterInnenbewegung [Association for the History of the Labor Movement], Vienna.

- From Günter Regneri, Luise Kautsky: Seele des internationalen Marxismus—Freundin von Rosa Luxemburg [Soul of international Marxism—Friend of Rosa Luxemburg] (Berlin:, Hentrich and Hentrich, 2013), p. 51.

- Rudolf Gädeke, Die Gründer der Christengemeinschaft: Ein Schicksalsnetz [The Founders of the Christian Community: A Web of Destiny] (Dornach: Verlag am Goetheanum, 1992), p. 350.

- In his letter to Werner Teichert, he specifies that “300 prints were sold for the benefit of anthroposophical friends and members of the Christian Community, who were imprisoned here or in Theresienstadt.”

- Both letters are in the Rudolf Steiner Archive, Dornach.