Co-creation has become a popular buzzword. But what does it mean for companies, employers and employees? How does the workplace become a place of human dignity and common good? Remco Bakker is a manager in the Dutch healthcare sector and spoke about this with Andrea Valdinoci, Executive Director of the World Goetheanum Association.

Andrea Valdinoci: We got to know each other when you were deeply involved at the Raphaëlstichting (Raphaël Foundation), where you were responsible for a huge organisation of more than 1500 co-workers. How do you define leadership?

Remco Bakker: There are different themes that are interesting and necessary for how we work and address problems together and grow as a community. I think it’s not just about participatory leadership, which is more the result of how we work, but in essence, it’s about collective responsibility. It’s about sharing responsibility and leadership equally—everyone has their own role and position (from a broader perspective). So, it helps to collect different perspectives from people in these diverse roles when addressing problems and questions because a co-worker may have a different perspective than I have as a managing director. We need each other to see the whole.

Simply put, there are different angles from which we can look at a problem. That’s not because the problem has different angles but because our responsibility for a topic as big as climate is not reducible to just climate. When you speak about climate, you also speak about farmers, the Dutch economy and politics, and entrepreneurs. You cannot reduce the view on climate to one aspect. So, one question or problem has many layers and affects many different spheres and people. If we have a materialistic mindset, our view on problems is too narrow. If we do not involve the people who need something to change or a problem to be solved—for example, in health issues, the person who has a health problem—we are missing a perspective that helps to solve the issue.

I know some entrepreneurs who might say, “This process takes too much time.”

We use a different language to address things, so it seems like it will take more time, but in the end, working with a different structure for solving a problem results in a different way of managing it and becomes more sustainable. Yes, you need three more conversations, and you have to invite eight more people; it seems time-consuming and difficult, you need consensus, and so on. But the outcome is much more sustainable and will resolve the issue permanently. Otherwise, we just find ourselves meeting again and again for the same problem. What happens nowadays, if we work in what I call a materialistic way, is that we solve problems instantly. That is what’s ”efficient.” But three months later, the same problem arises again. We start talking about it. We remember we handled it in such-and-such a way, and it was solved, and so we do it that way again. That is not a sustainable solution.

So, we work in a different time setting. And we have a different way of making decisions together because there is no one principal decision-maker for the entire process. Most of us are used to having a manager make decisions. However, if you work like we do, it is a group process—we decide from the center, not the top. Of course, we still need guiding principles. I am still the managing director. I do not decide what we do during a group process, but I still have the responsibility to carry it out on behalf of the whole.

In the World Goetheanum Association, we believe that developing associative ways of working and thinking in economy is a key for real change. You integrate many perspectives; you do not work solely towards your own goals but build a common goal.

I fully agree. I also work as a conflict mediator in neighborhoods, and I find it offers the best example of working associatively. Whether it is the neighbour’s dog that barks all night or the neighbour who parks their car in front of your house, resolving these conflicts follows the same simple principles: you create a setting where there is equality, space for autonomy (anyone can step out whenever it doesn’t feel good) and thereby a free will to participate, to take up responsibility. Investigating these three principles is the basic work in conflict management, from my perspective. You put people in contact this way, and in the end, they create their own solution. Not because I invented a solution—I could invent one because I can see how these two can work it out, and I can give suggestions, but it won’t solve the problem. The problem will be solved because they get in contact and start a discussion: What, really, is your problem? How can we solve it with the best outcome for both of us? Simply by listening to the other with recognition for each other’s worries, things start to open up, and people can hear and see and discover that there are different ways to look at the problem and, most importantly, that there are possibly different solutions. Then, the focus shifts from discussing which outcome is right to underlying principles and conditions, and a co-creation starts. It is not my solution, but it works for them. After that, you start challenging them: Well, what if it does not work? What will you do? And they design some underlying principles to overcome that.

What I am trying to say is that it is a local solution. Something emerges between two people in a totally different form than I would suggest or would have thought of. But it works. If I have the same problem with someone, I may come to a totally different conclusion. The form changes, but the principle stays the same. It is all about equality, autonomy and responsibility. To associate that with the sphere of work means that you need to orient toward local solutions. Maybe they have general principles, but it will look very different in Basel than in Münich, for example, because people in Münich live differently. The structure there is different: the economy is slightly different, the biographies are different, and so on. What we try to do materialistically is find a form or structure that works, and then we try to adapt it to different situations. But that does not work. We need local associative networks.

Can you tell us a little about how you came to this conclusion?

I discovered my personal way of working through trial and error. My first job as a managing director was not easy. I came into an organization with substantial financial, quality, and risk issues. The government was involved, and they wanted to take over because they did not trust what was happening there. Representatives of clients would not talk to me because they had no trust in the way the organization was operating. I had all these different problems with all these different perspectives. I could not solve things in the old way.

I’ll give an example that was a starting point for me. We had a swimming pool within the organization that had been closed by my predecessor, but the clients who had been swimming each day now had quality of life problems and health problems, because they couldn’t swim anymore. Re-opening the pool would cause huge financial problems. I thought: how am I going to solve this problem? So, I brought all the stakeholders to the table. These were very difficult conversations. They looked at me as if to say, ”You have to solve this. You are the managing director. It’s your responsibility.” And I said, “It is our collective responsibility. That’s the only thing I know.” Then, an interesting thing happened. After three conversations, we suddenly found ourselves in a moment of extreme tension. Afterward, I discovered that Otto Scharmer describes such moments. We were in huge conflict: three conversations and we still had no solution, the quality was getting worse, and they were threatening me.

Then, just as suddenly, by the next meeting, I found another swimming pool within the neighborhood. I told them I contacted this local swimming pool and we could get a few hours over there to swim. I still had a problem because I did not have transportation or people who would take charge, but I had a swimming pool. And then people started to step in! That was a fascinating moment. Children’s parents, who were not our co-workers, said, “Well, if that is the case, then I want to be one of the people who organizes this group’s transportation.” Someone else said, “I know someone who can drive the bus.” So we now had transportation, and somehow, it all started working out. Everyone stepped in and contributed to a solution. This would never have been solved if I had brought in money from my position of responsibility as a managing director. That would not have solved the problem. If I had ten people, it would not have solved the problem.

That was the real eye-opener for me and still is. I think this is what we need when we have severe problems with complex relationships. This is what we have to do. We can not solve a financial crisis without bringing in the people who are affected by it. We can not let a manager solve problems; we have to bring in the ones who are also connected to it. We have to bring them all on board to see something that is not yet there. They will always surprise you when you do that!

When did you get to know anthroposophy?

Early in my life, my father had an interest in anthroposophy, and I went to a Waldorf kindergarten. But when I was 12, I got to choose between two schools, and I decided the people at this Waldorf School were a bit strange, so I went to a regular school. I am still a bit disappointed about that, but okay. At age 18, I rediscovered anthroposophy myself. I thought: this is what I feel connected to. I got in contact with people who worked out of anthroposophy and started to read about it and work in anthroposophical institutions. I was fascinated by the way they looked at people, self-development, and development in the world.

Although I have studied anthroposophy since I was 18, the connection between leadership and anthroposophy came much later. I had a career during which I stepped in and out of anthroposophical institutions because I always also had difficulty with them in connection to the question of leadership we are discussing. We tend to talk about how great we are as anthroposophical institutions, how we provide a path, how we have found what other people are lacking, and, well, we are proud of telling other people what to do. But we do not often co-create with other people. We easily isolate ourselves from others, and exclusion creates opposition. This is a very general statement, of course, but it has always been my personal struggle and feeling that anthroposophical institutions tend to be turned inward and don’t connect to the outside. It’s a problem if you have a strong philosophy within a strong niche because it’s also a niche. You start to connect to each other internally instead of connecting to the world. I strongly believe that we have to connect with the world and that the world tells us if we are doing something that’s not really appropriate or fitting in. I think that’s the main reason why we still have difficulties within the Anthroposophical Society: we hang on to the rituals, structures, and forms we once found.

If I meet someone and open up, if I am really interested in what they tell me and ask a question, then I really want them to answer, and I really, really want to feel the consequences of that because it might be that they give me an answer which is very uncomfortable for me. That is true co-creation: you give me an answer, and what you are telling me is already starting to change me because you tell me something totally new. In essence, I wanted to know that, but it is difficult because it means I am starting to change, and I have to let go of my assumptions.

Let’s take a look at the World Goetheanum Association; we met in January at our regional day in Amsterdam at the IONA Stichting. We tried to build a space of trust and do something concrete together: to hear each other and draw out the group’s expertise. Maybe that resonates with the question: do we open up enough?

The first thing you describe is more a quality of the way we work together. We want to be in an open space with each other. We must have an open ear for each other, listen and try to explore problems or questions carefully and build a group together. At the same time, there is a purpose within the association. The people who form the association bring in this purpose. We can use examples of entrepreneurship or examples from different regional meetings. As an observer looking in, you can ask: What can we discover when we look at all these initiatives we are involved in? Is there a guiding thread or a core principle that tells us something for the association as a whole? If we look at it as an observer, we find common themes that we can predict will lead to guiding principles. And from these guiding principles, we can step in as an association, take initiative, for example, in the energy market, or build a collective for climate change or something else. But we have to take a few steps before we get there.

Maybe you can tell me a little bit about the Netherlands. Why does Anthroposophy feel more integrated in society?

This is a huge question. Personally—and this is only my non-professional, educated guess—I think it has to do with being a small country with different nationalities. There is a liberal climate on the one hand and a lot of opposition on the other. But we have so many opinions within our society that we have an instinctive urge to make it more inclusive. I believe this is why, in the Netherlands, anthroposophical institutions are more integrated and more liberal. Dutch people do not just take things for granted; they want to do things their own way. That is also the difficulty: we do not easily blend into one culture or community. But I think our entire history of holding different cultures within such a small country helped us learn to integrate more, live with each other, and accept that there are many ways of seeing and dealing with problems and that it is okay if you do things your way.

For example, health organizations adopted the same principles as anthroposophical institutions and somehow developed much faster and much more inclusively. Anthroposophical healthcare was never recognized for that. If you look at these developments in healthcare in the Netherlands, you find, for example, a movement called ”Passende Zorg,” which is about seeing people in their environment and adjusting to that: making sure that people can stay at home when it is needed, making sure that people stay healthy. I love the idea that anthroposophical initiatives could be totally visible in this movement, but, up until now, they are not visible enough—often, they are not even a conversation partner for the movement. Let’s try to open up more.

What is needed for this?

A few years ago, I was in Mondragon, in the Basque region of Spain. You can find models of co-creations and cooperation there. They work with three simple guiding principles, not with structures or forms. People have to contribute to the community, and businesses ensure that co-workers participate within their company, as a community, and as a whole. I was fascinated.

I spoke to all these wonderful and enthusiastic people and got a tour of Mondragon. I wanted to see it, feel it, and visit the mayor. The first thing I saw when I drove into the village was a supermarket, something I pre-judged to be completely commercial, non-adaptive, and aggressive, with no great policy for their co-workers. I was dazzled by what I found and asked them about it. They told me, basically, that we have these three guiding principles, and people live by them, so if this supermarket chain does not adjust to these principles, they will not have a base for their company here in the long run. That is exactly what this supermarket chain had done: they had to involve co-workers within the structure and bring something to the community because if they did not, then there was no commercial ground to be had there.

That is what we can learn. We have to define core principles, open up, care, step into a co-creative process, and trust in adjustments. This might bring about a form for supermarket chains that we have not discovered yet. Do not judge by the form, but step into the co-creative process. Do not tell society what to do, but contribute to society and bring in your own perspectives. That may be the connection to the question of leadership—that is what I am trying to do within my job, and I think that is what the Anthroposophical Society as a whole can do for politics and for society. Bring in your own perspective—not by proving you are right, not by convincing people, but by truly stepping into co-creating. You are equal to the other, so you can bring in your own perspective. We each bring a different perspective to things, and in doing so, in being consequent, new solutions will arise. It may not be my solution, but it is a solution in which I participated and took responsibility. By taking responsibility, I also have a responsibility for the outcome. These are all starting points for creating new forms and structures, participating fully and not just from a single point of view. Bring in this perspective.

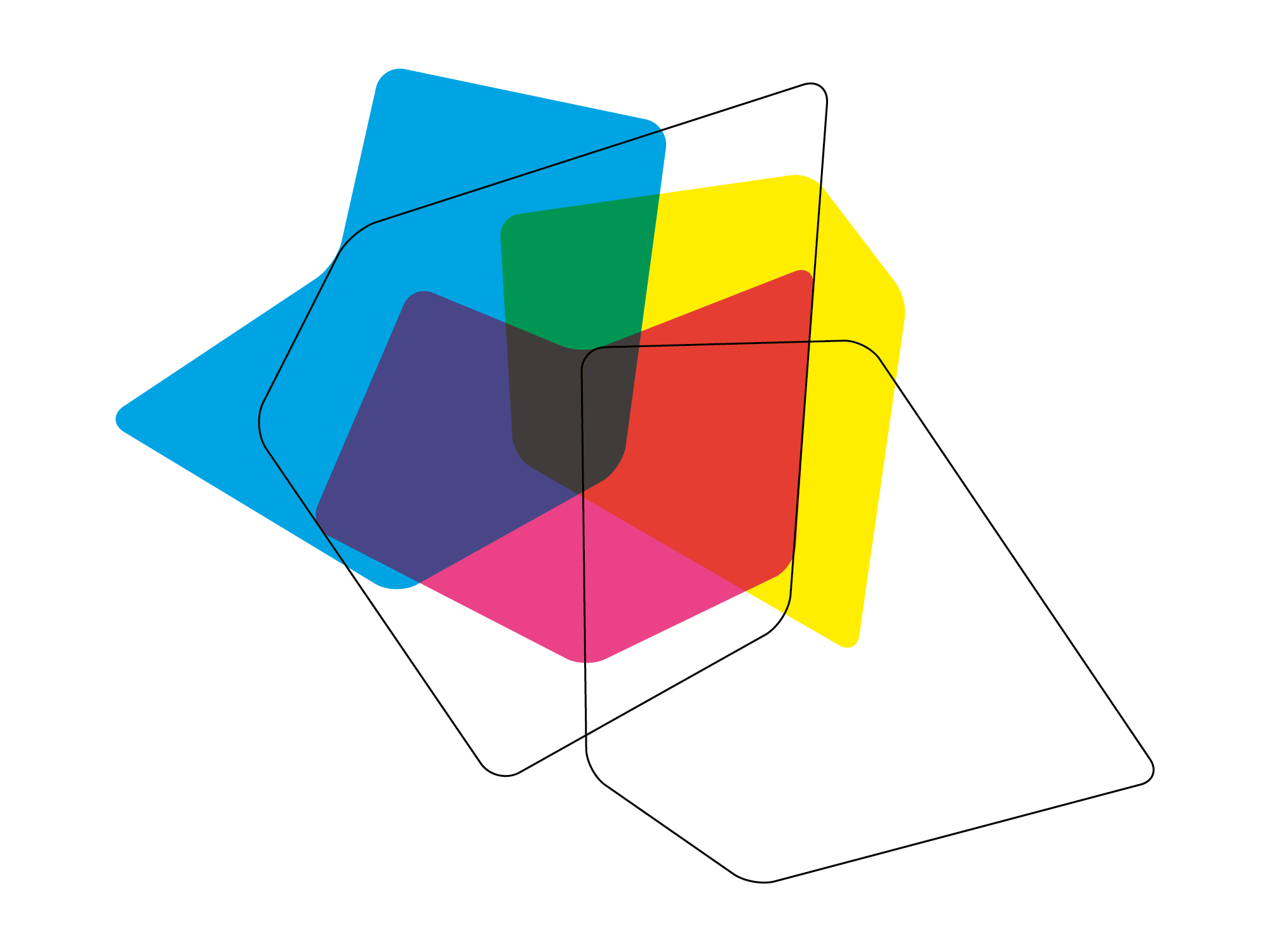

Illustrations Fabian Roschka