Anthroposophists have always heard that the Indian philosopher Jiddu Krishnamurti (1895–1986) was not the incarnation of the Maitreya Bodhisattva of the twentieth century foretold by Rudolf Steiner, the future Buddha, because Steiner dismissed Krishnamurti as such. Was it otherwise?

There are many candidates for Maitreya, but there has never been a clear-cut choice.1 It was Rudolf Steiner himself who emphasized that “the teacher’s authority and the faith in him should play no different a role than is the case in any other field of knowledge and life.” (CW 10; see also CW 130) So, as diligent students, let us begin by taking the liberty to ask: provided Rudolf Steiner’s account of Maitreya is not a chimera,2 what can be discerned of Jiddu Krishnamurti from an anthroposophical point of view? Let us turn to basic facts:

- Rudolf Steiner rejected the claim that a certain Hindu boy (Jiddu Krishnamurti) was the returning Christ (CW 28).

- According to Steiner, the Maitreya Bodhisattva in the twentieth century would consider it his most important task to point (CW 118, CW 123) to the etheric Christ (CW 130, CW 130).

So the question is not whether Krishnamurti, who is credited with a spiritual awakening exactly 100 years ago, was Christ. It is about a basic anthroposophical question: who was Maitreya in the twentieth century? Annie Besant proclaimed Krishnamurti as a partial incarnation of the latter’s consciousness.3

Life in Higher Worlds

In fact, Krishnamurti repeatedly warned against visions of supposed religious figures, and of Christ as illusions, and radically dismissed them.4 That he nevertheless counted on the clairvoyance of his audience with his teachings, seeing it as the result of meditation he taught, is clearly attested: “And in this process of meditation there are all kinds of powers that come into being. One becomes clairvoyant, the body then becomes extraordinarily sensitive. […] clairvoyance, healing, thought transference and so on.”5 But of course this does not yet include a heralding of the etheric Christ, even if in a rare ideal case it might indirectly lead to an encounter with him through clairvoyance. (see CW 118; CW 15)

In addition to visions in his early years,6 descriptions of supersensory perceptions, including those in the etheric, are found in Krishnamurti’s work, especially in his later life, in abstract allusions—for example, as “nothing”.7 This “nothing” is to be understood—just like love—as “not-a-thing”. It “is not negation” but means “not put together by [dead] thought”. According to Krishnamurti, the entire being of nature, and also the I of the human being, is just such a “not-a-thing”.8 Creation itself, however, with its inherent “death [which holds no fear]”, becomes at the same time the bearer of “love”9—something Krishnamurti had already expressed in his younger years in the deeply felt poetry and prose “From Darkness to Light”.10 At that time, he addressed the apparition of an unknown, deeply loved spiritual being who had appeared after difficult life struggles, as “My Beloved”—a being whom he saw everywhere, in all things, whom he wanted to tell everyone about, and whom he described in the most splendid colours.11 This world-encompassing Beloved—Krishnamurti at that time still used words borrowed from theosophical teachings—”was Krishna, were the Masters [of Wisdom], was the Buddha, and much more than these.”12 According to Steiner, however, Christ himself is the substance of the wisdom of all Bodhisattvas, including the Buddha (CW 130), and has permeated creation in a new way with his deed and his substantial love since the Mystery of Golgotha. (CW 91)13 And it is precisely to this that the “more”, death, love etc. in the quoted statements and writings of Krishnamurti about higher worlds seem to point, at least distantly, as if unspoken.

The Spiritual Beloved and the Damascus Experience

According to Steiner, the Maitreya of the twentieth century should, above all, teach humanity about the etheric Christ in order to “make the Damascus experience possible for many” in the future (CW 118), whereby the infusion of love (CW 133; CW 130) and real concepts (nota bene: not words or names; see CW 04; CW 121) about the “Christ event” (CW 130) play a role. This seems to be hinted at in a fragmentary way in Krishnamurti. It includes the exquisite lyrical eulogies to his spiritual Beloved and then his apprehension and teaching of love as something that follows on from death and eternity,14 which thus does not belong to the conditioning temporality of cause and effect and which is part of his answer to the question of whether there is a God.15 Similarly, knowledge of the fundamental difference between love on the one hand and unrelated time-bound cause and effect (karma) on the other would, according to Rudolf Steiner, be the mark of a true Christian even if the person concerned had never heard of Christ. (CW 143)

In this context, Krishnamurti’s repeated vivid descriptions, especially in the 1960s, of glorious rainbow-cloud sunsets in whose light the earth is immersed, are particularly worthy of investigation. Not only do they—like an echo of Steiner’s reference to Christ in the earth’s aura (e.g. CW 148; see also CW 118)—clearly approximate a description of auras and in one case even appear doubled,16 but moreover, despite all Krishnamurti’s other abstractness in spiritual matters, words such as the following should make us sit up and listen: “And everything was alive with color, and color was God, not the God of human beings. The hills became transparent.”17 What is described by Krishnamurti thus consists of:

- “God”, but not a (possibly abstract) human concept of God,

- love (in Steiner’s sense, to be understood as Christian), which is eternal, which is God,

- life-infused colors (not only) of the clouds in the sunlight at the end of a day,

- whereby the solid mineral world of the hills becomes translucent, transparent.

This again recalls an early text by Krishnamurti about his spiritual Beloved: “The sun was setting / As I stood on a hill-top, / Watching it disappear Behind the mountains. / In the midst of that radiance, / Clad in a cloud of yellow, / Thou wert seated. / The whole vast heaven paused in adoration. / The sky, the clouds, / In robes of yellow, / Were Thy worshippers, Thy disciples […]”18 It is the spiritual Beloved, who is “much more than Krishna, the Masters, Buddha.” Such a God of deep intimate love, who could previously be addressed as “Thou”, who “comes with the clouds” in a nature internally perceived, translucent and luminous, sounds somehow—contrary to Krishnamurti’s rejection of religious visions—like an experience of the Son of Man promised in the Revelation of John (1:7), reminiscent of Christ-love. It sounds, at least to some extent, like a form of the Damascus experience (Acts, 9:3-29) as foretold. (CW 118) Here life and death have a Golgotha-like relevance for Krishnamurti, because: “Without […] death […] there is no creation.”19

Vision of Deepened Concepts

As if from a distance, inwardly and outwardly connected with the vision of the Beloved, Krishnamurti’s consciousness seems to be approached by something that marks the transition from a state of relative death and new beginnings from “before”, to a death of total nothingness and real creation and love “at this time”20—whereby “behind” creation in the depths of the cosmos “beyond all the human efforts” lies a blessedly happy order.21 If we consider in all this the living nature of the “not-a-thing” in Krishnamurti as set out above, it becomes clear that in “death”, “nothing”, “creation”, “order’ etc., there is a living essence at work from Krishnamurti’s perspective. The insight gained from this, beyond the familiar world of the material, is expressed in his very words. On the one hand, real creation, through complete death, “now”, after “millions of years” of chaos,22 is initially felt in Krishnamurti’s own consciousness as a new possibility.23 On the other hand, what is felt in this way is connected with spiritual and physical nature outside, where creation out of death would ultimately have to be sought.24

In other words, complete death, love, and real creation in Krishnamurti are, according to his principle that the individual is the world,25 additionally also to be found in the world. And with this—albeit only in a way completely oblivious of history, subliminally and indirectly—Krishnamurti hints that, unlike in nature in the past (with the God of color clouds and love, perceived as alive, who is his Beloved, his teacher),26 absolute death as an intrinsic event has once and for all truly initiated new creation and life. The context resembles Paul’s succinct words referring to Golgotha: “Death has been swallowed up in victory.” (1 Corinthians 15:54) Is Krishnamurti implicitly suggesting here how the earthly-cosmic act of Christ can be conceptualized? According to Steiner, teaching this would indeed have been a task of the Maitreya Bodhisattva (CW 123).

Awakening and the Christian Path

Although he was born a Brahman Hindu 27, Krishnamurti’s life seems to have been similar in many respects to the inner and outer content of the stations of the Christian path of initiation set out by Steiner (CW 99): the washing of the feet (with the vision of the bowing down of “the higher self towards the lower self”; CW 199) as well as the “extraordinarily beautiful, highly cultivated” face that Krishnamurti suddenly saw next to him as a real higher being, which appeared as if the “body [were] purified [by it]” and which would one day “become his face”28; the scourging (enduring blows in life, the early death of his brother, his frailty and at times inexplicable, extreme sensitivity and all-over body pain 29); the crown of thorns (courage of faith?)—Krishnamurti’s mysterious purification headache. 30 These first stations each emerged from Krishnamurti’s intense meditation. Then: the crucifixion (freedom from the body?)—it seems Krishnamurti, with his out-of-body experiences,31 experienced his body like a house that he could leave and move into again; the mystical death (experience of oneness?)—Krishnamurti tells firmly of how, in a mystical moment, he is so fused with all life around him that he is this life itself;32 the burial (witnessing?)—Krishnamurti tells of how a vision awakened in him, “a comprehensive understanding” of “all the trees, all the mountains, all the lakes, every smallest insect”;33 and the ascension?

The last can no longer be comprehended externally, with ordinary thinking. Somehow it resonates in Krishnamurti’s “infinity” beyond the mind, and in the “not-a-thing” that he perceived as a power and grasped in its otherworldly “quality of being.”34 It seems akin to Krishnamurti’s “nothing” that “contains [everything]”, where beyond the “limitations of [ordinary] thinking […] there [is] still more. Much more.”35 And where there is a “door that […] must be opened”, where “a holy spirit [is] waiting […] for you to open the door”36, and in relation to which an “indescribable […] boundless energy” was also perceived in Krishnamurti externally.37 So was he Maitreya after all?

Krishnamurti, as one of the most outstanding minds of modern times,38 may have been grasped by the Christ-being in his own way. But whether he was Maitreya and able to introduce others to the encounter with Christ is another matter. Did he possibly lack conscious access to this? Or did the continued materialism of humanity that placed an obstacle in the way of seeing the etheric make his task more difficult? (CW 118) Did Krishnamurti ultimately fail because, being proclaimed as a world teacher at an early age, his soul nature suffered from the necessity to fight against false pride, forgetting his deepest mission as a result?39 It may be that the concrete guidance of human beings towards the etheric Christ by Maitreya, as foretold by Rudolf Steiner, is present in outline in Krishnamurti in narrative form, but a conceptual approach can only be sought with great difficulty, if at all, like a needle in a haystack of his illustrious teachings.

Many of these footnotes come from German texts. Should you wish to look them up, the correct page numbers can be found in the German edition of this article.

Translation Christian von Arnim

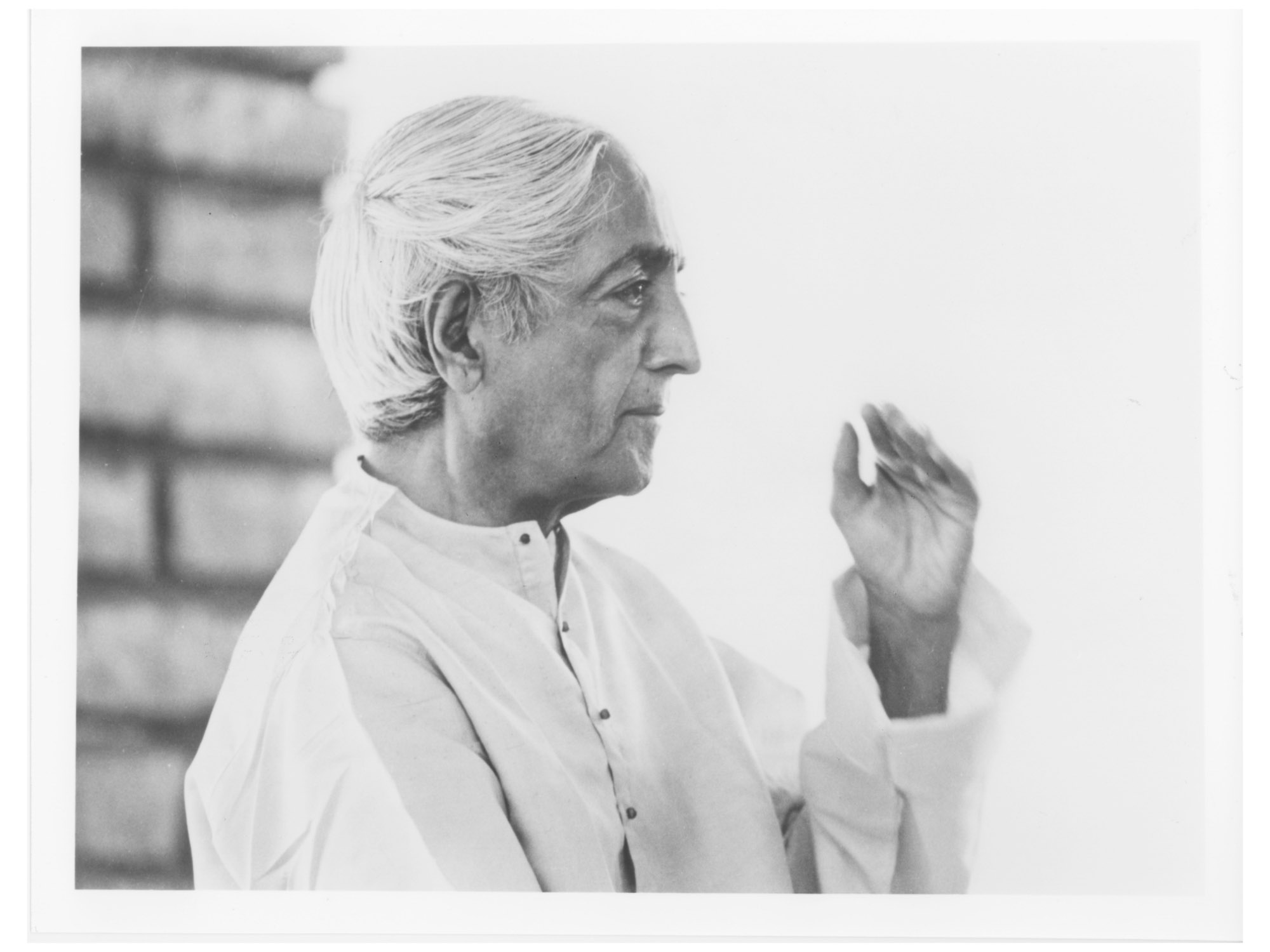

Title image Jiddu Krishnamurti, Photo: Hamid/Krishnamurti Foundations

Footnotes

- See Anthrowiki. Section “Die Bodhisattva-Frage innerhalb der Anthroposophischen Gesellschaft”. Anthrowiki Online Dictionary. Retrieved September 2, 2022.

- Rudolf Steiner himself might have been uncertain at times whether the incarnation of Maitreya would really take place in the twentieth century. In any case, he spoke about it partly in the subjunctive. CW 123.

- Pupul Jayakar, Krishnamurti (Freiburg, 2003).

- See e.g. Jiddu Krishnamurti, “You Are The World”, Chap. 7, 6 February 1969, 4th Public Talk, University of California Berkeley. In: J Krishnamurti Online, retrieved 15 August 2022.

- Jiddu Krishnamurti, “Truth & Actuality”, Chap. 9, 4th Public Talk, Brockwood Park, 1975. In: Krishnamurti.Net, Website, retrieved 16 August 2022.

- Jayakar, Krishnamurti.

- Jiddu Krishnamurti, “The innermost nature of the Self is not-a-thing”. J Krishnamurti, Website, retrieved 2 September 2022).

- Krishnamurti, Ibid.

- Jiddu Krishnamurti, Das Notizbuch (Frankfurt am Main 2009); see also Jayakar, Krishnamurti.

- Jiddu Krishnamurti, From Darkness to Light, n.p. 1929.

- Jiddu Krishnamurti, “Prose Poems– Poems III und VII”. In: Krishnamurti, From Darkness to Light. Jiddu-Krishnamurti.Net. Website, retrieved 2 September 2022.

- Jayakar, see also Jiddu Krishnamurti, An Interview in London. London 1928. Early Writings 1927–1928–1929. In: Jiddu-Krishnamurti.Net. Website, retrieved August 31, 2021.

- Quoted from Anthrowiki: Christ. “Das Ich im Menschen […]”, retrieved September 3, 2022.

- Krishnamurti, Notizbuch; Jayakar, Krishnamurti.

- Jiddu Krishnamurti:”Does God exist?” J Krishnamurti. Youtube video, min 7.30, retrieved September 2, 2022.

- Krishnamurti, Notizbuch.

- Krishnamurti, Notizbuch.

- Jiddu Krishnamurti, The Immortal Friend, 1929 n.p. Online edition. In: PDF Room. Website. p. 53, retrieved September 5, 2022.

- Krishnamurti, Notizbuch.

- Krishnamurti, Notizbuch.

- Jayakar, Krishnamurti.

- Jayakar, Krishnamurti.

- Jayakar, Krishnamurti.

- Krishnamurti, Notizbuch.

- Jayakar, Krishnamurti.

- Jayakar, Krishnamurti.

- Jayakar, Krishnamurti.

- Jayakar, Krishnamurti.

- Jayakar, Krishnamurti.

- Jayakar, Krishnamurti.

- Jayakar, Krishnamurti.

- Jayakar, Krishnamurti.

- Jayakar, Krishnamurti.

- Jayakar, Krishnamurti.

- Jayakar, Krishnamurti.

- Jayakar, Krishnamurti.

- Jayakar, Krishnamurti.

- With worldwide recognition, see e.g. ”Quotes about J. Krishnamurti” in J Krishnamurti., Website, retrieved August 22, 2022.

- See Samael Aun Weor, Sexology, the Basis of Endocrinology and Criminology, 1959, “The Krishnamurti Case” in Glorian. Website, retrieved August 22, 2022.