A look at the connection between humans and architecture illustrated by three buildings in Dornach. Piet Sieperda is in search of Rudolf Steiner’s concept of architecture.

We come to know what we might describe as the outermost part of our being, that which proceeds through the action of our etheric body on our physical body, in a spatial system of lines and forces. If we carry this spatial system of lines and forces, which is basically continually active in us, out into the world and arrange matter according to this system of forces, if we detach this system of forces from us and arrange matter according to it, then architecture comes into being.1

If we look at the human being in their vertical form and feel what happens in this form, then there is an unfolding of forces downwards, towards the feet. On the other hand, there is an unfolding of forces upwards, towards the shoulder girdle to which both arms are attached. We can use these arms to lift and carry things. This means that the forces develop from the centre of the body towards the shoulder girdle.

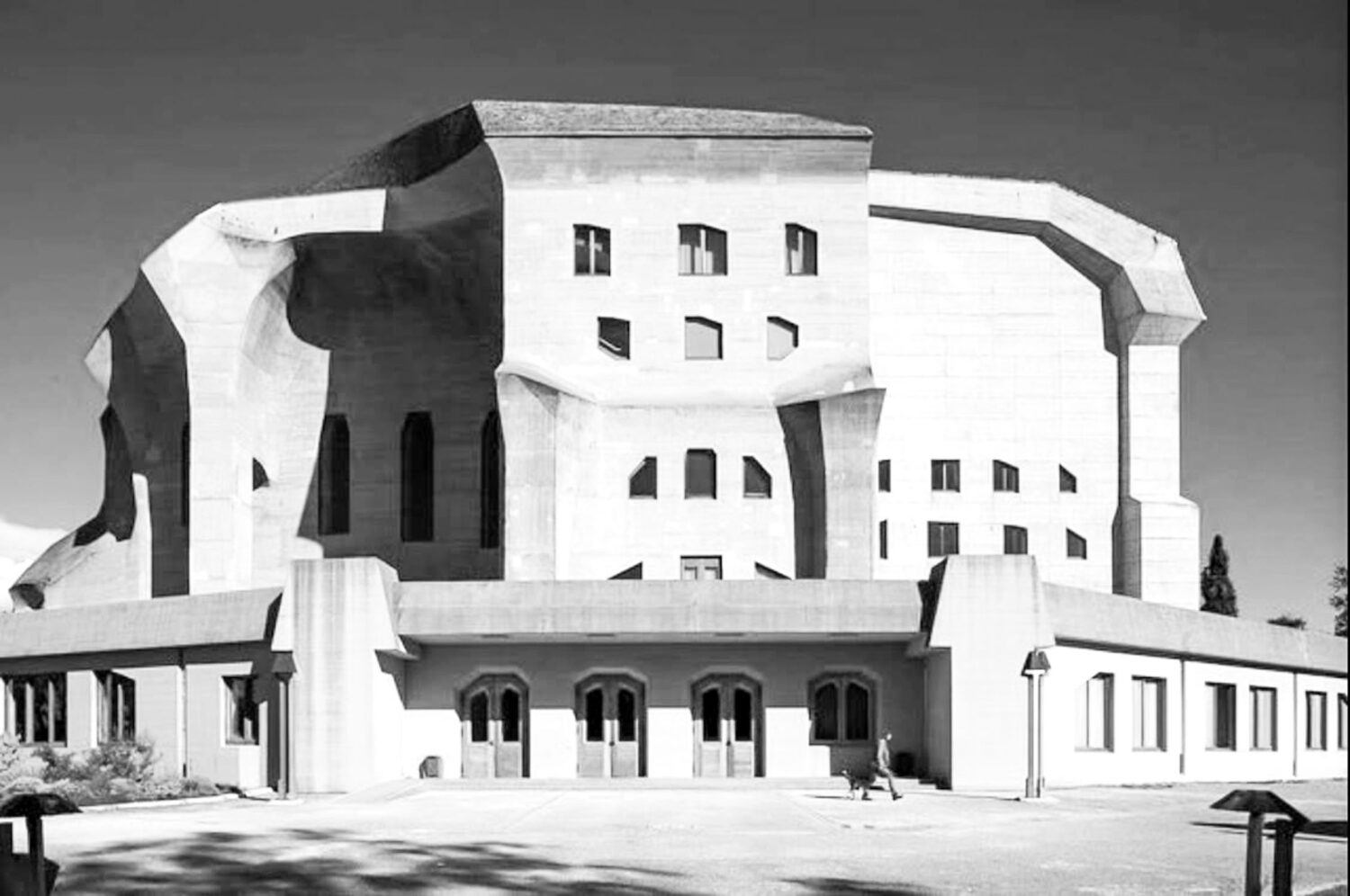

If we investigate the hill overlooking Dornach, we see three buildings by Rudolf Steiner which we can relate to these forces in their development: the Haus De Jaager (1921), the Eurythmeum (1923) and the Second Goetheanum building (1925). Here we see this upward force, towards the shoulder girdle, as an unfolding of forces from the centre of the building upwards, supporting and keeping up the roof. And downwards we also see – but less extravagantly – that the unfolding of forces downwards is made visible. There is another unfolding of forces that Steiner incorporates: that in the forward direction – just as the human being transitions from a standing position into a walking movement.

If we look at the three buildings, we can see in them this unfolding of forces. That does in fact seem to describe the whole concept. In the Eurythmeum entrance, seen from the east side, we see a combination of the upward and the forward movement. On the street side of Haus De Jaager, this movement cannot be seen. It is only when we go around the house to the garden side that we see the forward movement in the roof above the studio. These two movements and their interplay can be seen extremely powerfully on the Second Goetheanum building.

The Mass Modeling and Design Process

The architect begins by creating a mass model based on the required space. In the case of the Eurythmeum, it is a simple rectangular volume with two floors. The original model has the eurythmy practice room below and a studio above. In Haus De Jaager we have a studio area on the street side and a residential house on the garden side, combined in two areas: a rectangular and a more rounded shape. The mass model of the Second Goetheanum building consists of five parts, at the back a large cube-shaped part in which the theatre, offices and workrooms are incorporated. The auditorium is wrapped in a large trapezoidal block that adjoins it. And there are also three stairwells.

In the second phase of the process of architectural creation, the architect will design the mass model using the force system mentioned above. This is an artistic process. It is important that the architect, as far as possible, brings to expression the laws of this system of forces.

In this phase, the main thing is to experience the system of forces in your own body. The architect then has the feeling that they are using their own characteristics, their own system of forces, to design the building. It is important that malleable material is used, easily controllable, so that the development of these forces is well visualised.

We should also point out that the mass model can be further prepared for the later design phase, if necessary. We see this with the Eurythmeum, where the floor above the ground floor shows a forward movement, so that only then the massive columns become a necessity. In the same way, we see on the second Goetheanum that the great roof – which is more or less placed on the mass model – essentially makes the great movement forward.

Walking and Standing

There are few references from Steiner about his architectural concept. In 1923 we find some remarks during a question and answer session at a youth course. Steiner approaches the human being’s walking and standing from the perspective of architecture in Stuttgart on February 14th, 1923: «Insofar as we study the human being as they move and stand, we get the form of architecture. A perfect building is nothing other than the human being’s perfect standing and walking. […] this static and dynamic aspect in the human being.»2 When standing, the forces act upwards and downwards, and when walking, forwards. Steiner adds the concepts of static and dynamic and says that the perfect structure contains both elements: static and dynamic, standing and walking.

If we look at our three buildings again with the knowledge we have just acquired, we suddenly see that all three consist of a static and a dynamic part. The Second Goetheanum shows this most clearly. If we approach this building towards the south portal, we have the back with the work areas on the right. In terms of design, this is static. On the left side, on the other hand, we see an enormous dynamic in the front part, which is also dynamic in its design. This is the area where guests are welcomed, the theatre entrance, ticket sales, information, coffee and tea, toilets and a meeting point for guided tours. The perception from the front is the most dominant, that’s where we have to be. We really have no business in the back area with the workplaces.

We see something similar with the Eurythmeum. Seen from the side, this building shows a large door. To the right we see a dynamic part and to the left of this door is a kind of extension that is very static. Here there seems to be both a static element on the back side and a very dynamic element on the front side. In Haus De Jaager we find something similar. The studio represents the static element and the living area the dynamic element. However, the contrast here does not seem very articulated. The static part is not quite a rigid rectangular shape; force lines were also made visible. A second quotation from the lecture of December of 1914 could help us here: «Everything that is present architecturally in the laws of the assembly of materials is also to be found in the human body. The art of building, architecture, is a projection outside of ourselves into space of the human body’s own laws.»3

We have already found a dynamic front and a static back in the buildings. Do we also find this in the human body? Without being very aware of it, our back is a much stronger static element of our body than we actually think possible. Nothing is initiated from the back that we can relate to our actual daily functioning. In our daily functioning, we are mainly active in the front of our body, operating actively, expansively towards the world and also towards our fellow human beings.

The Frontal and Medial Planes

The plane that separates the static part of our body from our dynamic front is called the frontal plane. If we look at our three buildings again, we can roughly indicate where this frontal plane is. While we began by speaking about the development of the lines of force as the basis of Steiner’s architectural concept, we must now note that both at the Eurythmeum and the Goetheanum the building elements behind the frontal plane show no signs of these lines of force, but that they have been built statically. So it is not as simple as we first saw. However, at both the Eurythmeum and the Goetheanum there is an obvious difference between the volume of the front part and that of the back part. The front part is much more expansive.

Now the frontal planes of both the first and second Goetheanum building can confuse the unsuspecting observer on the hill. As this is a main building with a number of adjacent buildings, it appears that this plane becomes dominant for the whole site. When we look at the site, we notice that all the buildings built behind this frontal plane have been given a static appearance. They include the three Eurythmy Houses (1920), the Publishing House (1924) and Haus Schuurman (1925). This also explains why no development of force lines is visible in these buildings. Steiner obviously wanted to make the contrast between static and dynamic visible in the surroundings of the Goetheanum.

When we talk about the laws of the human body, the medial plane is so obvious that it is almost embarrassing to talk about it at all. We know from daily experience that our bodies and those of our fellow human beings are symmetrical. In artistic anatomy, we call the plane that separates the left half of our body and mirrors it with the right half the median plane. This plane is also a basic law of the human body. It enables us to give direction to our actions and to orient ourselves in earthly space, also with our vehicles and tools. For this reason they are also symmetrical, otherwise we would not be able to control them or work with them.

Rudolf Steiner’s architectural oeuvre leaves no doubt about symmetry. With the exception of the Eurythmeum, which is clearly a special case as an extension of the original Haus Brodbeck, all the buildings on the Dornach hill owe their symmetry to his hand.

One of the goals revealed in Steiner’s architectural work is to bring an architecture into the world that has as close a connection as possible with the human being, and in particular with the human body as a manifestation of our earthly existence. The great goal is to create architecture that has a deep affinity with the human being. The decisive factor is how much we feel connected with the building.

Steiner’s Building Impulse

The most characteristic feature of Steiner’s approach to architecture seems to be the dynamic part of a structure. You have to be able to see from the building that it stands well on the ground, that it supports the roof well and that it shows forward movement to a greater or lesser extent. In addition, there is a static part at the back. But that requires much less creative effort than the dynamic part of the design. Of course the front and back must fit well together.

It is important that static functions should also be more or less housed in the static part of the building. We can also see whether functions can be distributed across the left or right part of the building. In this way there is a viable concept with which we can create building projects of the future. A crucial aspect in this respect is a client who wants something like that.

With regard to the buildings under discussion in Dornach, we can ask ourselves to what extent we feel connected with them. If we know that this style is still in development, this can be an indication of the extent to which the architect has succeeded in finding themselves as a human being in this style. And thus also the extent to which an architect has allowed themselves to be guided by this architectural concept, thus contributing to the realisation of Rudolf Steiner’s building impulse.

Translation Christian von Arnim

Title image Haus de Jaager (1921), garden frontage, south elevation, static. All Photos Peter Zimmer