Beyond Rudolf Steiner, Hilma af Klint (1862–1944) is one of the most well-known students of anthroposophy in the world today, but her relationship with Rudolf Steiner is often maligned. Spending a considerable amount of time in Dornach through the 1920s, af Klint left behind a rich body of work that could clearly be called spiritual-scientific research. Charlie Cross interviewing Anne Weise from the Rudolf Steiner Archive.

You’ve been deeply involved with Hilma af Klint for quite a while now—how did you encounter her work?

In the past few years, Hilma has shot into public consciousness, as if from nowhere. She wasn’t known for such a long time, but in the past decade or so, there have been numerous worldwide exhibits. A huge exhibition planned by the Swedish Museum of Modern Art in Stockholm was in Berlin and then traveled to other places as well, and that was the first time that af Klint was presented in such a big way. I accidentally happened to be in Berlin during the time of one of these exhibits, even though I was living in the US at the time. I wanted to meet a friend and we looked at what’s going on in Berlin, and we both independently found this exhibition, not knowing anything about Hilma. I was immediately excited about her art. It was quite interesting. They had two levels — the lower level presented her Theosophical period, showing her earlier work with automatic writing and so on, and the upper part exhibited her later work which—I felt—was so much more clear. I was so excited about the exhibition that I went there the next day with another friend.

Several years later, when I started living in Switzerland, I was visiting the States, and there happened to be a big exhibit of Hilma’s work at the Guggenheim Museum in New York, in 2018. I went with a friend to the Museum, and it was four and a half hours before we looked at our watch for the first time, which is amazing—I’m usually exhausted after an hour or so at a museum. It was probably in part the architecture of the Guggenheim, where you can always look out into the distance and see other paintings far away, and then you can concentrate on the one which you are closest to—one can breathe in there. But otherwise, I think it was Hilma af Klint’s paintings. The exhibition was full of people, and everybody was excited. You could hear it from every corner, from every walk of life—people were excited. It ended up being the most successful exhibition ever at the Guggenheim, which is 80 years old, and quite popular artists have been exhibited there.

But there were ways that she was presented in connection to Anthroposophy which surprised me. I brought home the catalog. There was a discussion of an art studio visit by Rudolf Steiner and accusations that Steiner was jealous of her work, and other things that we don’t have to repeat in depth. I had a feeling that this was a misrepresentation, so I started researching, and I found out that this story was just not right. I’m at the Rudolf Steiner Archive. Everyone has access to our records, but I can just go to the cellar and look for them. I also got access to her notebooks from the Hilma af Klint Foundation and looked for clues and hints about her relationship to anthroposophy and Steiner. It was a wonderful exhibition, but there might have been some prejudice.

It seems that with her discovery, art history had to be rewritten, because her abstract work prefigured Kandinsky and Mondrian, and as a woman, she became a feminist icon. I could imagine that it would be an easy or neat narrative for Steiner to become a sort of patronizing antagonist to her.

That would fit the narrative. People have written about her connection to anthroposophical art, but people still assume some tainted relationship. However, the documents do not support that. Rudolf Steiner did not have any reservation against this new type of art. There’s a written recollection of Rudolf Steiner after he visited the Swedish artist Frank Heyman in Göteborg. He describes his art in this short note, really praising it—which looks like Cubistic art. This is not wet-on-wet watercolor or what people assume when they think of anthroposophical art. And there is no proof of him saying negative comments about her work. He said a few things concerning specific paintings of Hilma’s, explaining what was going on, giving some understanding—but nothing broad-reaching. She was trying to meet Rudolf Steiner in order to find out what her paintings meant, what they signified because she wasn’t sure at that time.

At that time she was a member of the Theosophical Society and had been a part of a group of women called ‘The Five’ that was essentially channeling. She would be sort of possessed to make these paintings and almost lose her self-consciousness. So it makes sense if she was acting as a vessel for other beings, that she might not fully understand what was coming through her and want some help figuring it out!

And I’d add that these women were aware of this danger, they prepared themselves—they were often fasting, reading the Bible before they did anything, and praying. They kind of set the spiritual tone for the type of beings they were inviting. One of the women was a medium, and the others would write down the messages of the spiritual beings speaking through her. They also did some automatic writing, and there are many notebooks full of these notes and drawings of flowers and symbolic forms in Hilma’s later work. At one point Hilma af Klint had a request, as she calls it—written in her notebooks—that she would do this big project: The Paintings for the Temple. In a matter of a year and a half, starting in November 1906 and finishing in Spring 1908 she created 111 paintings in this big, abstract manner. It was hard work, I can imagine, and she was very serious about it. She was painting out of the guidance of her spiritual teachers, and it went quite quickly. Nevertheless, she didn’t quite know what she was painting at that time, so she wanted to ask Steiner, who came to Sweden for the first time just before she finished this huge set of paintings.

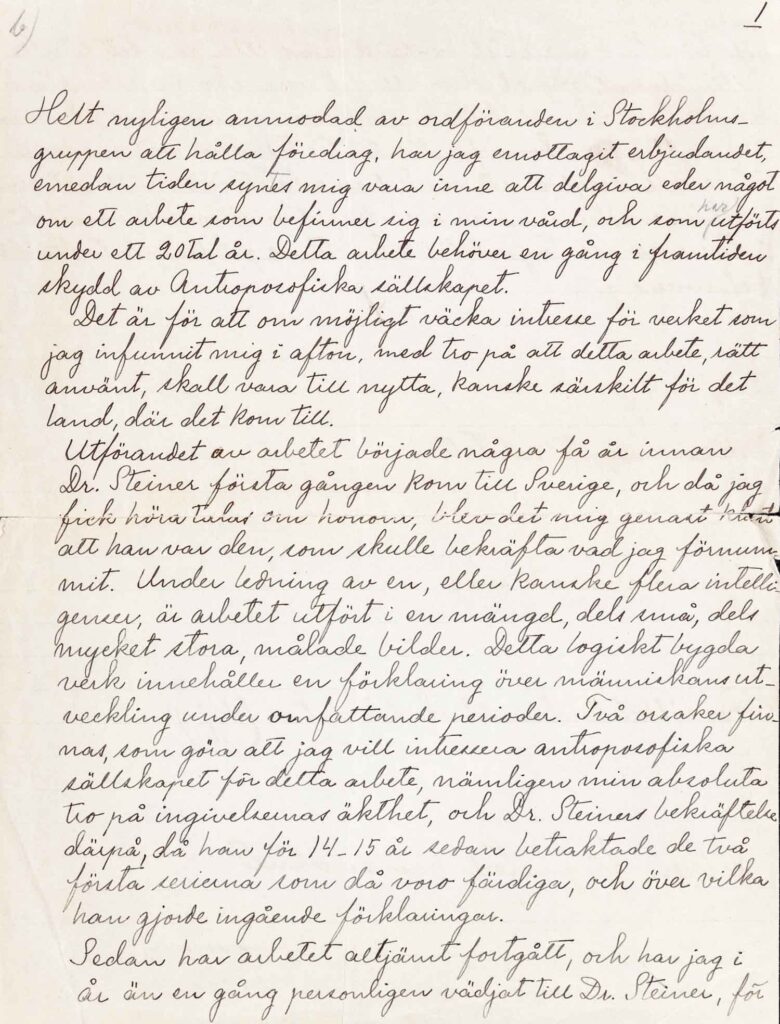

“The execution of the work began a few years before Dr. Steiner first came to Sweden, and when I heard about him, it was immediately clear to me that he was the one who would confirm what I had perceived. Under the guidance of one, or perhaps several intelligences, the work is executed in a number of painted pictures, some very small, some very large. This logically constructed work contains an explanation of the evolution of mankind over vast periods of time. There are two reasons why I wish to interest the Anthroposophical Society in this work, namely, my absolute belief in the authenticity of the inspiration, and Dr. Steiner’s confirmation of it when, 14 or 15 years ago, he looked at the first two series then completed, on which he made a detailed explanation. Since then the work has continued, and this year I have once again personally appealed to Dr. Steiner to find out about the work. Whether it should be preserved, or whether it should be destroyed. The answer was, that it would be detrimental to let it disappear and that it could be used and useful.” Hilma af Klint, Notebook 1101, page 35, used with permission of the Hilma af Klint Foundation.

Can you give us a little bit of a timeline of Hilma’s life and work and encounter with anthroposophy? How did that influence her work?

Absolutely. She became a member of the Theosophical Society very, very early, in 1904, and was deeply involved with it—she took part in group meetings and so on. And as you know, until Rudolf Steiner founded the Anthroposophical Society in 1912, he was the leader of the German Section of the Theosophical Society, giving lectures, and in 1908, he came to Stockholm, to Sweden, for the first time, on the 30th of March. That was the very first time she had heard of him, as she wrote in her notebook. And the subject matter he was bringing really excited her—he gave lectures to members of the Society about the Rosicrucians, which she had always tried to find out more about. She approached him right at the first day of his lectures to ask, “Is my work influenced by the Rosicrucians?” And, “Can I be in contact with Rosicrucians?” She didn’t speak German, so she had to use a translator. This is all written down in her notebooks.

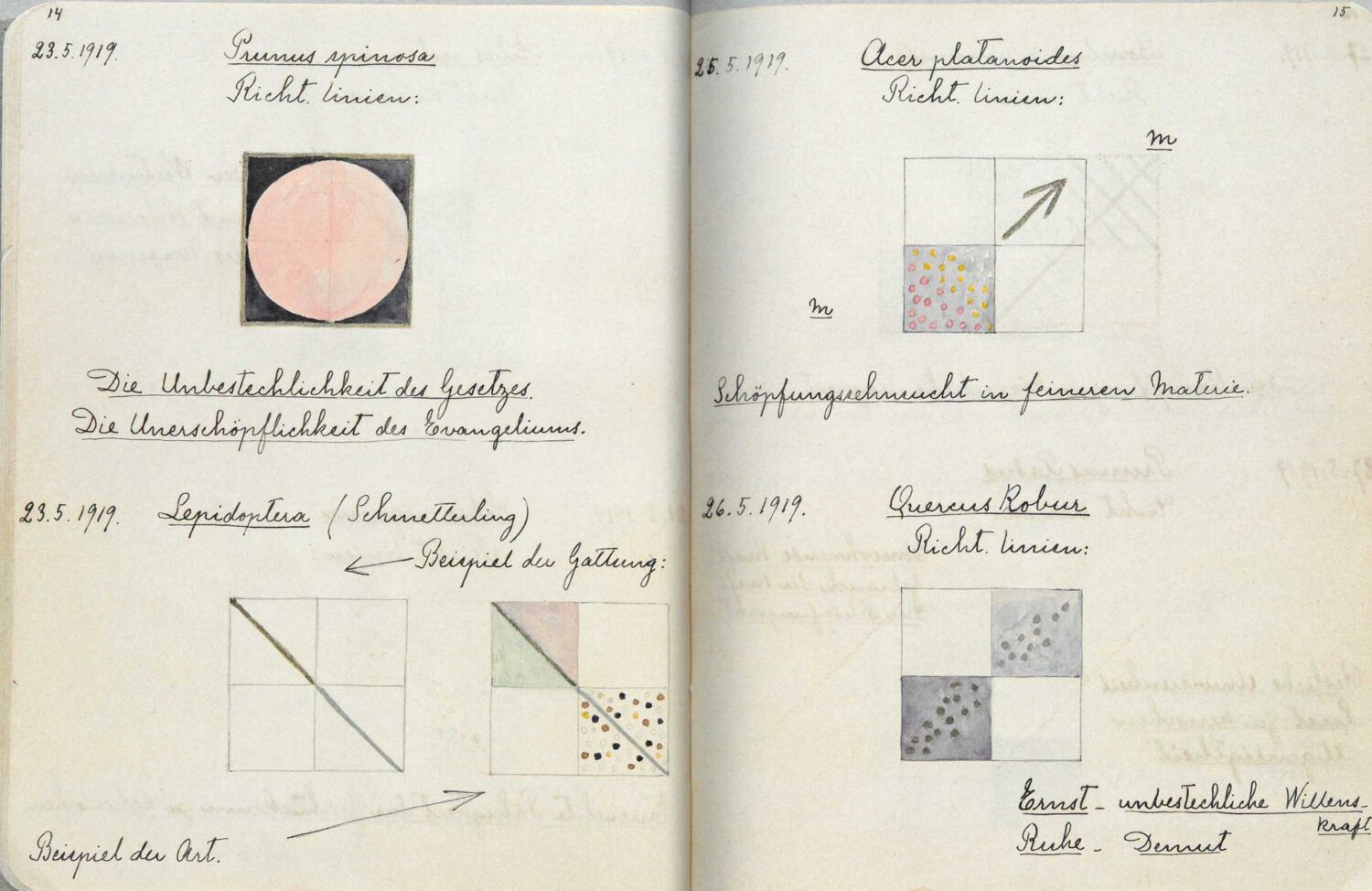

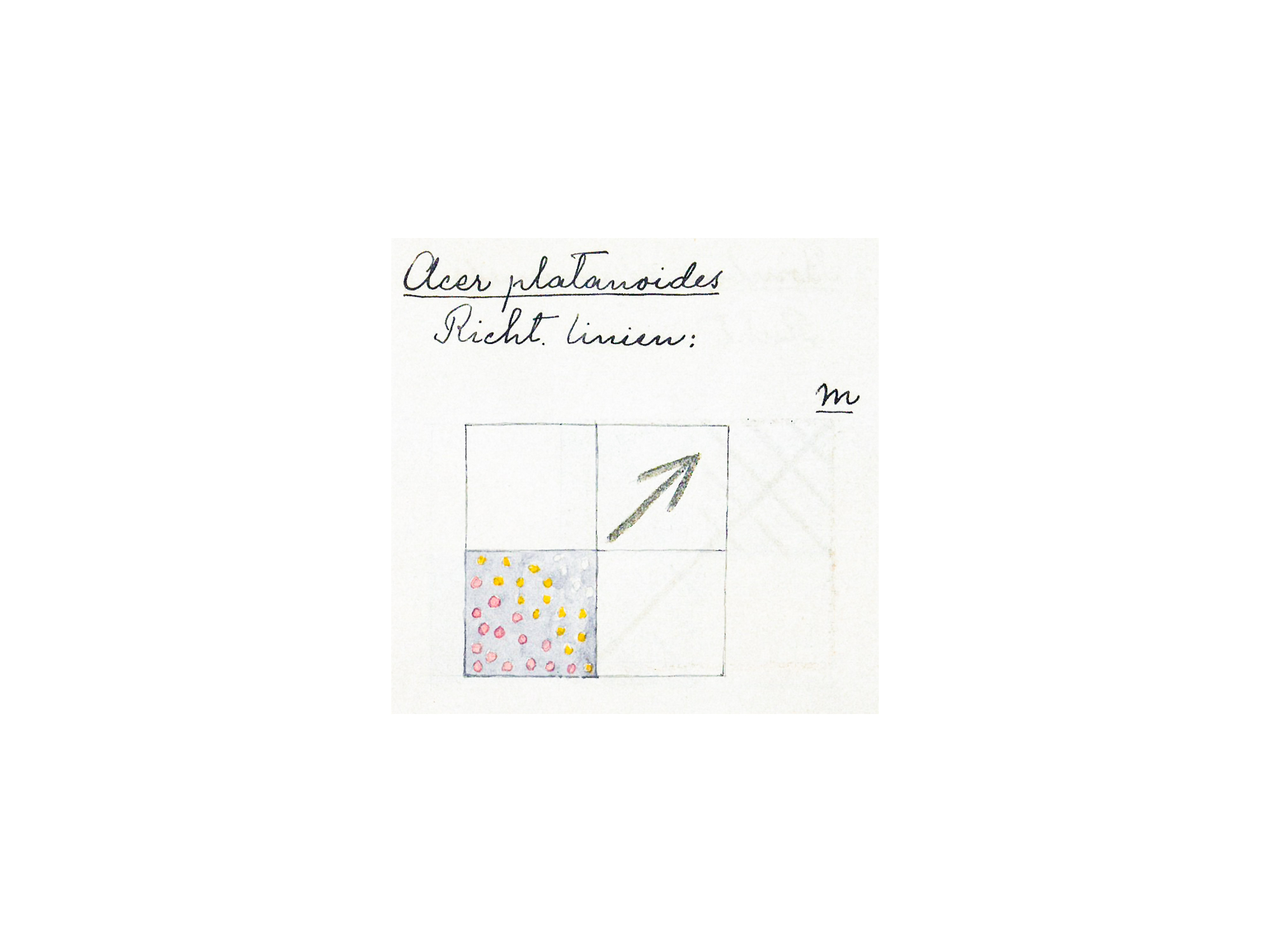

The same day there was a public lecture, Goethe’s Esoteric Answers to the Riddles of the World, which was also fitting to her because she would later on observe nature regularly and would try to come to some kind of general Urpflanze (Archetypal Plant) like Goethe, with her Richtlinien (Guidelines) in which she was trying to find some essence of a plant. These were his first two lectures, on that first day, she met and spoke to Rudolf Steiner. The following day he spoke about the Rosicrucians again, the next, he gave a lecture on Der Ring des Nibelungen, and then The Social Question and Theosophy, and finally about the Mystery of Golgatha and about Initiation. So these were the first few lectures that Rudolf Steiner gave in Sweden and Stockholm, and she must have attended them all.

She completed the Paintings for the Temple in April of 1908—just four weeks after Rudolf Steiner was in Stockholm. And after she finished, she wrote him a letter asking him to visit her. We don’t have that letter—we don’t know the content. We are aware of it because there was a second letter written by her to him, which we have in the archive here, in which she is asking him for a visit to her art studio in Stockholm, because her paintings are so big and she cannot bring them to him. She wrote in English: “My teacher has sent you in my way and I think it is to help me understand the work.” She asked him to come to Stockholm on his way back to Berlin from Oslo, a huge detour—a bold request, in my view! He responded that he doesn’t have time and that anyway, she has her own spiritual teacher, and she trusts her own teacher, and as long as that’s the case, she doesn’t need him—but if she needs occult advice, he would be there for her. They both wrote in bad English, because of which, it’s sometimes hard to know what they really meant.

I think it’s funny that these letters were in bad English. Somehow the image of these two great souls struggling to communicate through a foreign language is comical.

I so wish they would have both written in their native language—it would have been more clear what they really meant!

And in general, there are some points of unclarity. It’s unclear when he really visited her, and the literature today is all over the place in discussing this topic. It’s clear that he visited her. I believe it was probably 1910 when he was there again for a lecture tour in Stockholm. We know for sure that he did visit her and saw her paintings. That is proven. She didn’t have an art studio in 1910, but she could have shown the paintings anyway.

In 1908, her mother became blind, and she had to take care of her because all the other siblings were married, with families. She was the only one who stayed single, and therefore it kind of fell to her to take care of her mom. She had also just completed the first chapter of her Paintings for the Temple, so she must have been extremely exhausted. Considering that and having to take care of her mom, and that she had to change her living quarters as well and didn’t have her art studio anymore—she stopped painting for a few years. It was a completion of a phase, not an interruption.

People sometimes try to blame that on Steiner, thinking that she met with Steiner right away, he said something discouraging about her work, and she stopped painting for four years.

Exactly. Well, it’s not even proven that he was there at her studio in 1908, which would be the foundation of that assumption. Documents suggest that it was in 1910. She gave a talk to the Swedish Anthroposophical Society in 1924, where she said Steiner saw her paintings 14 years previously. And if you would have painted over 100 paintings in this huge format over two years, you might need a break, on top of having the new struggle of her mother being blind. These are two big possible reasons for the pause in her painting.

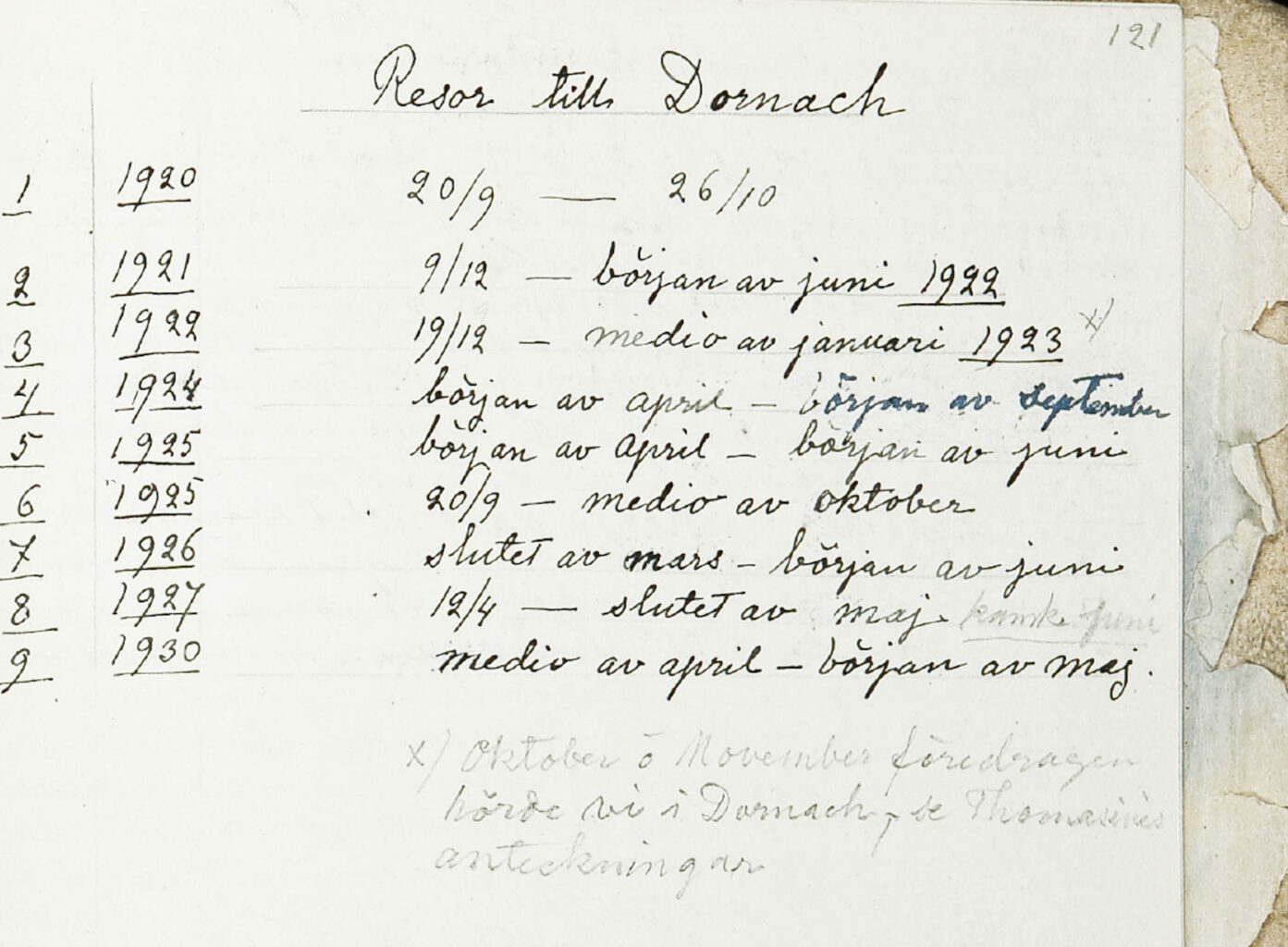

In 1920, Hilma’s mother died after having been blind for 12 years. A few months later Hilma came to Dornach for the first time. She immediately became a member of the Anthroposophical Society and a member of the First Class as soon as it was founded. She stayed a member of the Society and of the First Class until she died. There is other information out there stating otherwise.

I read that she spent a lot of time in Dornach until 1930 or so, and then she had a big split or something.

She came to Dornach very frequently for about 10 years, staying for up to half a year at a time, taking part in lectures, and so on. The first time she came, she witnessed the opening of the First Goetheanum and took part in the first Hochschulkurs in October 1920, the first time scientific courses were offered in the Goetheanum. She was also here when the First Goetheanum burned down in 1922/23. Another time, she arrived just a few days after Rudolf Steiner died. She also wanted to become a member of the Rudolf Steiner Association which Albert Steffen planned to found in 1926 but never came to be. There is a lot of evidence that she took part in the life here. In her notebooks, there are notes about anthroposophical artists who lived here at the time. In 1928, there was a big world conference in London about anthroposophy organized by Dunlop, and she took part with a few of her big paintings and had an exhibition, she even gave a talk about her paintings. The program says: “Miss af Klint was showing her studies of Rosicrucian symbolism.”

That was 1928. Nevertheless, I think she did want to have them exhibited here in Dornach as well which most probably didn’t happen. Peggy Kloppers-Moltzer, a Dutch artist, tried to help her to find some possibility for her to exhibit in Holland, which didn’t work out either. I think after all these attempts, she decided, herself, that the world was not ripe for her paintings. Around that time, in 1932, she decided that her paintings should be hidden until 20 years after her death. And then she put the sign ‘x’ in front of her notebooks to indicate that. It took longer than 20 years. We don’t have evidence of anything Rudolf Steiner said about this. They did have at least one meeting here in Dornach—there is proof for that. She asked him in 1924: “What should happen with my paintings? Should I burn them? Are they worth anything?” And for a long time, we didn’t know what his reaction was. But now we do know—he said that it would be a pity to let them be destroyed, that they are valuable!

So maybe it was more that she was frustrated with Dornach in the 1930s, or other life circumstances that kept her from coming back or moving here.

There were several things I believe—first of all, she was not that young anymore. She turned 68 in 1930. But in 1930, there was a General Meeting of the Anthroposophical Society, she was here at that time, and we can assume that she took part. That must have been a really difficult one.

The Anthroposophical Society was a little crazy after Steiner’s death.

It was really hard after Steiner’s death, to figure out how to go on without his leadership and guidance. In 1930, she wrote in her notebook that there are dark forces over the Society in Dornach at the moment—which is interpreted as, “Oh, she was done with Steiner. She was done with Anthroposophy.” No—she was done with what was happening here in Dornach, with many so conflicts flaring up.

Which is so understandable and so human.

Yes. She never came back after 1930 but continued to be active regionally. She gave a talk in Stockholm to members of the Anthroposophical Society in 1937—there are a few notes in her notebook about what she spoke about.

Can you describe the work that Hilma af Klint left to the Goetheanum? Can we see Steiner’s influence, and how does it compare to her previous work?

This is a topic that needs further exploration. One thing is clear: From the beginning, she had two sides, which she brought together wonderfully. On the one side, she was an artist, who painted out of influences from the spiritual world, and in the beginning, she wasn’t so much aware of what she was doing. On the other side, she was already at that time a scientifically working woman. For example, she drew pictures of horses for veterinary textbooks. She left a whole book that is full of her drawings of all kinds of objects.

She was a scientific illustrator!

Exactly. So she continued being scientific in her work. You can also see for example, how she had always put her paintings in a particular order, in series and groups on particular themes. After she met with Steiner and learned about anthroposophy and new ways of art, she tried to implement that. She listened to and studied lectures about Goethe’s Color Theory for example. She painted lots and lots of wet-on-wet-paintings and continued with her path of observing nature.

In 1919, the First World War had just ended, and she wanted to contribute something healing. She wrote: “Where war has torn away the plants and where the animals have been killed, there are empty spaces which could be filled with new forms if there were sufficient faith in the human imagination and in the human capacity to create higher forms.” (HaK 431, p. 60)

She observed plants almost daily, from 1919 to 1920. She studied them, drew their physical appearance, and then, through deep observation, painting, and meditating on them, she perceived what she calls ‘Richtlinien’, or guidelines—a kind of essence of the plant. They are not so easy to understand, but she developed these sort of geometrical shapes, seals, or symbols, I call them an essence of the plant she was depicting. Steiner suggested that when you observe nature and then work with and through these sense impressions meditatively, that there would be a metamorphosis. In How to Know Higher Worlds, in connection with the exercise to meditatively observe the withering and blossoming of a plant, Rudolf Steiner described, that they then form themselves into spiritual lines and figures, of which the observer had previously no idea of. And that these lines and figures also have different shapes for different phenomena, and that there would be nothing arbitrary in these lines and figures.

To finally respond to your other question, she drew nearly 100 of these plants on paper, which she gave to the Goetheanum, as well as a notebook with these small Richtlinien. The Hilma af Klint Foundation in Stockholm has a copy of this notebook as well.

You can see the process Hilma af Klint undertook: At the beginning of her work, she was more like a tool of her masters in the spiritual world, she painted very quickly—The Paintings for the Temple, for example, were painted very rapidly. She herself as a conscious human being wanted to become more and more the master of her paintings. She practiced throughout her life, I think, taking in other influences—in particular what anthroposophy contributes about art, spiritual practice, and Goethe’s Art Theory.

I find it so interesting that she’s been so popular, but in some ways, she hasn’t been understood properly because people have just rejected, basically, the latter half of her life, instead of taking an interest in this dedicated research that she did alongside anthroposophy.

Although some experts try to separate her from the influences of anthroposophy, I think most people that visit an exhibit, like at the Guggenheim, don’t care. There’s just something that speaks to them. They’re immediately taken by her art, and that’s what matters.

But if we look at these small little seals, you can see that they’re so related to her earlier work as well. So she’s actually leaving a sort of path or sort of process.

I agree. These plant observations, which she did in 1919, and 1920, in many ways, are steps on this. We all are on some sort of path. She herself took on the observation of the plants. She then worked through these impressions, meditating on them. And through painting, there’s a process of connecting with another being. You’re already meditating, in a way, with your hands. And then she came up with these seals, essences—Richtlinien. This for me is a daily practice, and is clearly a work out of an anthroposophical impulse.

It’s spiritual-scientific research! Through artistry, through direct phenomenological observation, and through meditation. Her paintings became more her own – they were more mature.

This is for me a change in her work.

And, especially coming from within anthroposophy, you can see it as a very distinctly anthroposophical undertaking.

Yes, undertaking is a great word. You can see the process, where the physical appearance of the plant and the Richtlinien are linked. She didn’t just come up with the Richtlinien as such—she first of all observed the plant, adding the Latin name and some other information: the seeds, specific flowers, or leaves. This is scientific work for me, spiritual science. Later on in the 1920s, she did the same process through wet-on-wet—not as thorough and as many, but there are quite a few watercolors.

This question is maybe a tangent, but a friend of mine suggested that these images, especially the sort of distillations, could resemble some of the images or motifs created by some of the indigenous folk in the northern parts of Scandinavia. Are you familiar with this?

I’m not so much familiar with the ones in Scandinavia but with the Native Americans in the US. I think there might be a connection to all of these because they are also kind of translating spiritual substance into a form, you know, which is quite geometrical. What an interesting potential research question.

Images from Hilma af Klint’s notebooks published with permission from the Hilma af Klint Foundation and the Albert Steffen Stiftung.

In writing about Hilma af Klint, it may be a good idea to refrain from hyperbole. The ”very, verys” and the ”extremelys” don’t clarify anything. It may serve her true story better to put off drawing conclusions or setting exclamation points.

Is it possible that as long as af Klint was essentially painting and writing under the influence of not-well-identified beings, Steiner may have experienced reservation about the result? And is it possible that when she began working under her own direction, the results were simply more reserved, less spectacular? Perhaps she needed third period in her life, after the theosophical and the anthroposophical ones, in order to fulfill her own destiny as an artist.

When you see, in current exhibitions on at least a couple of continents, pyramids, swans and all manner of quasi-theosophical symbols, you see that her work is an inspiration for younger generations of artists. For what that is worth.

The ”experts” here in Sweden are Daniel Birnbaum, Kurt Almkvist and Ulf Wagner. Now that would be a conference panel for the 2020’s!