The long anticipated and hoped-for conference of the Georgian Youth Society Parzival took place in August. In a moving account of the event, inspired by Georgian song and myth, Nathaniel Williams reflects on thoughts about social threefolding arising from the conference keynote talks.

When I first arrived at the Goetheanum in January of this year, I re-connected with members of the Youth Society Parzival from Georgia. I had met some of them a few years earlier at one of the Youth Section’s international network gatherings. I remember that first meeting and some of our discussions about higher education and how conscious I was of the radically different tenor they brought to the conversation. Afterward, they reached out to me with their intention to create a youth conference, but this was indefinitely postponed due to public health and travel restrictions. They did not stay idle, however. When I met them again this past January, I learned that they had channeled their energy into building a small Waldorf school in the small village of Matsevani, Georgia. Members meet at this building every Friday to study together and then spend the weekend working together and running after-school programs for local children. This fall, they are launching a seminar for young people who are interested in anthroposophy.

When we met back in January, the group shared their intention to finally pull off the conference and asked if we could focus some of the Youth Section work for the year around this project. The result was the International Youth Conference “Principles of Healthy Social Life,” which took place in Matsevani from the 9th-13th of August. The main idea, theme, and structure of the conference had been well prepared before I got involved, as it had been in the works for years. There were lectures, workshops hosted by young people from around the world, a film screening of the movie “Zusammenspiel” 1[interplay], a screening of a movie about the building of the school in Matsevani 2, eurythmy exercises, outings in the countryside and village, and a concert.

The Knight in the Panther Skin

The evening of the concert, at the end of the fourth day, was cool—a welcome relief from the heat of the day—as the crowd found their seats outside the school building. About half of those gathered had walked from their houses in Matsevani. The others had come from further afield to attend the conference. The choir gathered on the porch and, in half silhouette, backlit by a few lights, they shared from the treasury of Georgian song. There were songs of love, of war, and of ancient liturgical celebration. The melodies emerged in the dusk, as they have for centuries, shaping and inhabiting the soul.

A few kilometers away, in a larger village, evening was swallowing the giant industrial ruins of the collectively planned society of the Soviet Federation. Industrial infrastructure and giant warehouses, blurred by the vegetation creeping over them, testified to the power of the elements and abandonment. They were disappearing in a double shadow—of night and of the receding remains of six decades of communism. In nearby fields, haystacks were piled up in a manner only known in the West through the paintings of Monet and Van Gogh. Cows wandered, sometimes attended, sometimes not, through the street and town. As the darkness thickened in the town, the hilltops, many crowned with ancient churches, still spoke with the last colors of dusk.

The songs led everyone inward and into the night. They were images of the search for the Golden Fleece, of the great God chained to the mountains, his liver exposed, of the arrival of St. Nino and the spiritual stream of Christianity. All of these images had been evoked during the previous days, and now they played between the young people under the stars. So many shooting stars!

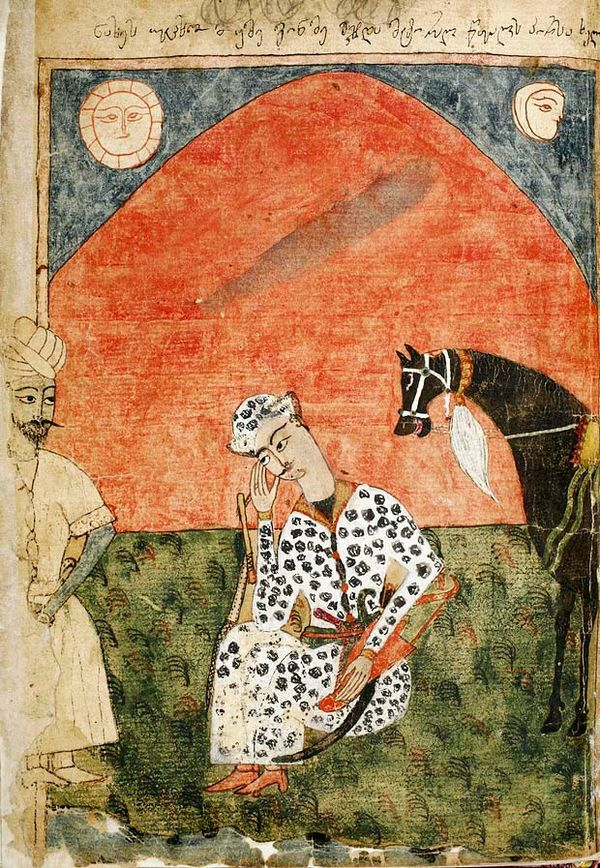

The poet Rati Amaglobeli had introduced many of these images four days earlier, in the opening lecture of the conference, “Georgia and Anthroposophy.” He’d begun with the story, which re-emerged again and again during the conference, of Shota Rustaveli’s The Knight in the Panther Skin—an epic poem written in Georgian in the 13th century. Many of those who’d made the pilgrimage to the conference had never heard of this poem, even though they had arrived at the Shota Rustaveli International Airport in Tbilisi.

Amaglobeli had introduced the images in broad and panoramic style, stretching over millennia, to facilitate an encounter with Georgian culture for the young people from afar. How he introduced the story and images made this possible—it was clearly a variation of the quality I had noticed years before in my conversations with the youth society and in my many trips to the Ukraine. In the West, using the word soul is “out of date,” but it is one of the best colors for this quality: the soul was thinking, and the pictures were ensouled. It was as if one could think of nothing without eternity looking over one’s shoulder. And since everything in the presence of the divine is more profound, so too, were the thoughts developed in this element. This tenor stands out perhaps most clearly for those from the West due to the contrast it evokes. After reading Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment, Saul Bellow reflected on the immediate charismatic appeal of Russian literature, “Their conventions allow them to express freely their feelings about nature and human beings. We have inherited a more restricted and imprisoning attitude toward emotions … We lack the Russian openness. Our path is narrower.”3

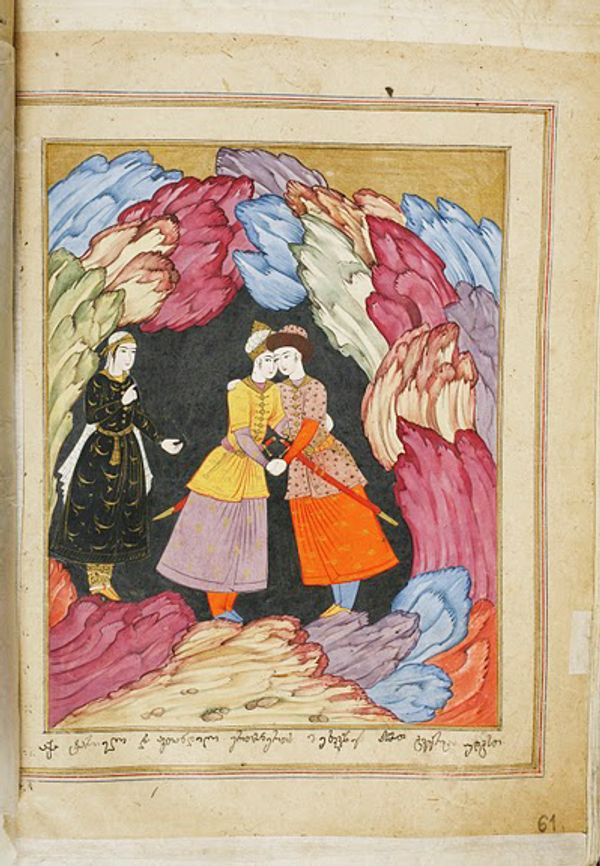

The poem opens with a hero, Avtandil, and his king on a hunt that is interrupted by a mysterious knight, beautiful to behold, dressed in a panther skin. Avtandil and the king set out with a host of warriors in pursuit of this knight and find him doubled over in sorrow, weeping violently, with no interest in them, totally consumed by some sublime despair. He kills the small army sent to pursue him without effort and disappears. He is the great Tariel. Avtandil sets out to discover who this man is, unable to wed his beloved until he fulfills this task. Thus the epic tale begins.

The broad arcs and characterizations by Amaglobeli turned the hunt into a search for the divine. Tariel, the sublime spiritual seeker. Amaglobeli suggested it contains a nascent Georgian form of anthroposophy, one that includes the Platonic spiritual orientation of Georgia that, according to Amaglobeli, has much to learn from the Aristotelian influences of middle Europe and anthroposophy in particular.

As these imaginations unfolded under the open sky in an outdoor lecture hall, Amaglobeli turned to the more recent history of Georgia. He spoke of the famous Georgian writer Konstantine Gamsakhurdia (1893-1975), who had attended lectures of Rudolf Steiner and had testified on a radio interview during Soviet rule, at a time when such interests could lead to arrest or worse, that one of his greatest inspirations was anthroposophy. The son of this writer, Zviad (1939-1993), went on to become one of the most well-known dissidents during the Soviet era in Georgia, founding the Helsinki Watch Committee with his spirit brother Merab Kostava. These two friends, Zviad and Merab, worked on some of the first translations of Rudolf Steiner’s works into the Georgian language. They explored the connections between anthroposophy and the mysteries and culture native to Georgia. And they signed their letters to one another: Avtandil and Tariel. Zviad Gamsakhurdia eventually became the first democratically elected president of Georgia after the fall of the Soviet Federation.

On that first evening, as we sat on the hillside in Matsevani, one of Zviad’s sons, Konstantine Gamsakhurdia, joined Amaglobeli. He shared his own memories and spoke of how these great stories shaped his father Zviad’s life. Konstantine has written broadly on his father’s life4 and translated portions of his scholarly work on Rustaveli into German.5 Thirty years ago, the Gamsachurdia government was sidelined in a coup, and not long after, his life was taken.

The presence of the Russian state was felt within the words of those who spoke that evening. Twenty percent of Georgian territory is currently occupied by the Russian military. For many from the West, this occupation is perhaps understood in a shallow way as a recent development. In the context of this event, a much older, more complex relationship emerged for the listeners who were visitors from afar.

All these images and impressions accompanied the songs that filled the night. For a moment, Georgia became the center of the world.

Paths to Transformation through Social Threefolding

At least half of the young people participating in the event were from Georgia, and perhaps the most intriguing parts of the event for them were the guest speakers and workshop leaders. The young organizers had scheduled five lectures in the event, each one to two hours in length. There was a deep interest on the part of the organizing team to learn from the older generation and a real intention in setting aside ample time for these lectures.

Philipp Jacobsen gave a presentation titled “The Human Organism as a Model for a Healthy Society and for Social Threefolding.” In it, he sketched out ways of looking at the human body, physiology, and psychology from a threefold perspective, as an impetus for a similar threefold view on social life, following Rudolf Steiner’s indications.

Vova Khvitia, a native of Georgia, gave a lecture titled “Historical Preview of Social Forms.” He led the participants through stories and imaginations of the mystery centers and events of Georgia, the West (Europe), and the East (Asia). This was another intriguing opportunity for those from the USA (of which there were many) to experience that the Americas were not even mentioned, with Georgia as the center of the world.

In his lecture, “An Analysis of Contemporary Social Life from the Point of View of Social Threefolding,” Gerald Häfner shared the story of the writing of the current German constitution. He spoke of how, years ago, he had suspected that the references to voting which it contains were being misinterpreted and that, in one area in particular, this had led to a disenfranchisement of German voters to draft their own proposals for legislation and bring them to a binding vote. Not only did he pursue his suspicions to discover that he was correct, but he went on to lead a movement for the expansion of direct democracy in Germany. During the presentation, the stories of the political goals of Häfner and his peers, their strategies, and ultimately, their successes stood out as moments of encouragement. Many young people in Georgia had been on the street only months before protesting the proposed “foreign agents law.”

I was invited to give the last presentation under the title “The Paths to Transformation through Social Threefolding.” Moved by what I had heard and seen, I shared impressions of the aspiration to connect heaven and earth, of Marxian communism, Christianity, and associative economics.

The imagination of a knight wearing a panther’s skin, wandering in the wilderness partially insane and burdened by a sublime sorrow, became an unexpected inspiration to explore associative economics. This great picture expanded, arcing centuries, and the giant collective industrial infrastructural ruins of the Soviet era began to shrink. How amazing to see the Marxian experiment shrink like this. Before the end of the Soviet Union, almost half of the world’s population were living in a state whose constitution was inspired by Marxian ideas. His influence is only comparable to great religious figures, though his message was explicitly secular. He wanted to unite heaven and earth by overcoming human spirituality. He wanted to make the earth into a heaven. He wanted a human spirit that was united with the earth. What strange resonances emerge when this is thought of in connection with the mysteries of Christianity. There, we also find a striving to bring heaven and earth together. The radical challenge these mysteries present is of the God that lived a human life and died a human death. The vision of the transformed earth, of the resurrected human, and the overcoming of death are prophetic imaginations of a unity of heaven and earth.6

In the pre-Christian mysteries, the earth and the earthly personality cannot accommodate the divinity. One powerful example of this appears in the teachings of Buddha, where the self reaches the divine through the withdrawal from desire and attachment. This spirituality of withdrawal from the personality leads to an element of divine life, of an unbinding, of Nirvana and connection with a divine selfhood. This is the basic gesture of Platonism as well. One of the strongest impressions of Rustavelli’s poem is the dramatic and perpetual suffering that the striving Tariel experiences in his longing for his beloved (the divine). He is wandering in a wilderness clothed in the skin of the panther, which he tears and soils every day and which is combed, cleaned, and repaired at night by a servant of his beloved. We find in this image, as in Plato, that the earth and human life are necessarily sources of illusion and suffering. He is not able to inhabit the element nor to be free of it. How do these mysteries relate to the call of Marxian thought? How are the mysteries of love to transform the earth and the most basic dimension of human collective life, the economy?

Both Khvitia and Amaglobeli referred to the importance of the European mysteries for the future of Georgia. Khvitia mentioned that part of this lay in a central European ability to connect spirituality with outer, practical life: to unite heaven and earth. One of the most moving testimonies of this task can be found in the economics course Rudolf Steiner delivered one hundred years ago.7 Steiner developed an economics which perhaps can be understood today better than before. He foresaw the increasing global character of the economy, developing a sociology of trade that is only now being proven by recent research in the social sciences.8 The world economy today carries within it the potential to release a particular stream of solidarity (beyond nations, cultures, and religions) through cooperation and association. He characterized how a certain variety of love is latent right below the surface of current economic conditions and how these can be consciously taken up, releasing their potential for the good.

Today, this is not only theory but an effective and impressive fact. One example is the GLS bank, and another is the CSA movement.9 We find large associations of businesses and consumers who are actively working toward such a vision of economic life in the benefit corporation movement and the work of B-Lab.10 It is perhaps through the West that this penetration of earthly life with this particular variety of love can find its proper scale and application. It is in the re-interpretation of economics as a question of the good, as a place of solidarity and cooperation, that we see one of the greatest promises currently at work in the USA. It is an impulse that found clear articulation as part of the impulse of the independent School for Spiritual Science. It is based on a sociology wherein “true price” can emerge, a price that can lead to voluntary changes for the good, in both consumption and production, through association. It is no centralized economy, but it is also not a free market of competition.

This great question, this question of reconciling the spirit and the earth, this question of Marxian thought and of the Christian mysteries, is a question many young people carry with them today. Many will not speak about it like this. I would not have spoken about it like this had I not been to Georgia, a center of the world.

Title Image The group of conference attendees in front of the Parzival centre in Georgia, Photo: Emily Watson

Footnotes

- Zusammenspiel.

- Aufbauprozess des Bildungsraums

- Saul Bellow. Saul Bellow: Letters. Penguin, 2010 xxxiv. The relationship between the West (USA) and Eastern Europe was a deep interest for Bellow. In his book “More Die of Heartbreak”, where he tries to draw out “the Ordeal of the West”, a certain encounter with evil through full identification with the personality, with constant reference to the culture of eastern Europe and thinkers like Soloviev. Soloviev famously characterized the task of the west in this way, something that was not taken up in the east where the full human element was not developed, and the spirituality remained in an immature state, yet one with promise for the future.

- Konstantin Gamsachurdia. Swiad Gamsachurdia: Dissident – Präsident – Märtyrer. Perseus-Verlag, 1995.

- Swiad Gamsachurdia. Die Bildsprache In Rustawelis Mann im Pantherfell. 2010.

- Rudolf Steiner. Christianity as Mystical Fact. SteinerBooks, 1997.

- Rudolf Steiner. Rethinking Economics: Lectures and Seminars on World Economics. SteinerBooks, 2013.

- David Brooks. “Opinion | People Are More Generous Than You May Think.” The New York Times, August 31, 2023, sec. Opinion.

- Trauger Groh and Steven McFadden. Farms of Tomorrow Revisited. SteinerBooks, 1998.

- Make Business a Force for Good.