Does art have a real effect in the world, or has it become merely a platform for politics? Our author traveled to a world-famous art exhibition in Italy and found a collection of works that conveys the idea of becoming “foreign” and transparent.

The 60th Venice Biennale opened in April with the title Stranieri Ovunque, Foreigners Everywhere, and features almost 90 pavilions and 331 artists, many of whom are exhibiting internationally for the first time. The focus is on the lesser-known: queer artists, indigenous artists, outsider artists, and folk artists, who have migrated between the global North and South, or who live in exile and diaspora. It is a celebration of outsiders.

The Political in Art or the Politics of Art

Art can’t change the world, but it can change our view of it. This statement by Brazilian curator Adriano Pedrosa is understandable in its realism but disappointing at the same time. Can art do no more? In times of crisis like ours, his statement seems like a justification that art has value despite its helplessness in the face of terrorist attacks, glide bombs, and melting glaciers. If art can’t prevent the senseless killing of human beings, it can at least work to stop the exclusion of those who think and live differently. It can train and broaden our perspective so that we learn to think more inclusively.

If art has to justify itself, hasn’t it already lost its value? And further, with all due respect for art as a mental practice and an intellectual field of discourse, I actually believe it can and does do more than simply change our habitual views of the world. The subtle and sometimes subversive effect of art is omnipresent in everyday life and not just when we go to museums or concerts. Imagine a society entirely without art—how extremely dull and dreary! Everything would be dominated by exclusion, surveillance, and prohibition, and every expression of art would be suspect because art is not a game, or, in fact, precisely because it is a game, a serious and uncontrollable game that no one can ever entirely dominate, not even those who produce it. The enormous force that competes with the law here is freedom. That’s why art doesn’t need politics. And certainly, when art unfolds in its own right, it naturally has an impact on society and thus becomes, if you like, “political.”

When the Biennale leadership has to justify itself and legitimize itself in the face of political pressure from society, I become suspicious and wonder whether art hasn’t simply become a medium solely for political agendas. Pedrosa’s chosen title, Stranieri Ovunque, Foreigners Everywhere, is a case in point: it’s the most political title in the history of the Venice Biennale.

Am I missing something essential here? Let’s take a step back for a moment. It’s quite possible that my inherited and acquired worldview is preventing me from seeing how the art world is currently transforming. Let’s start from the beginning.

Learning to Alienate Yourself

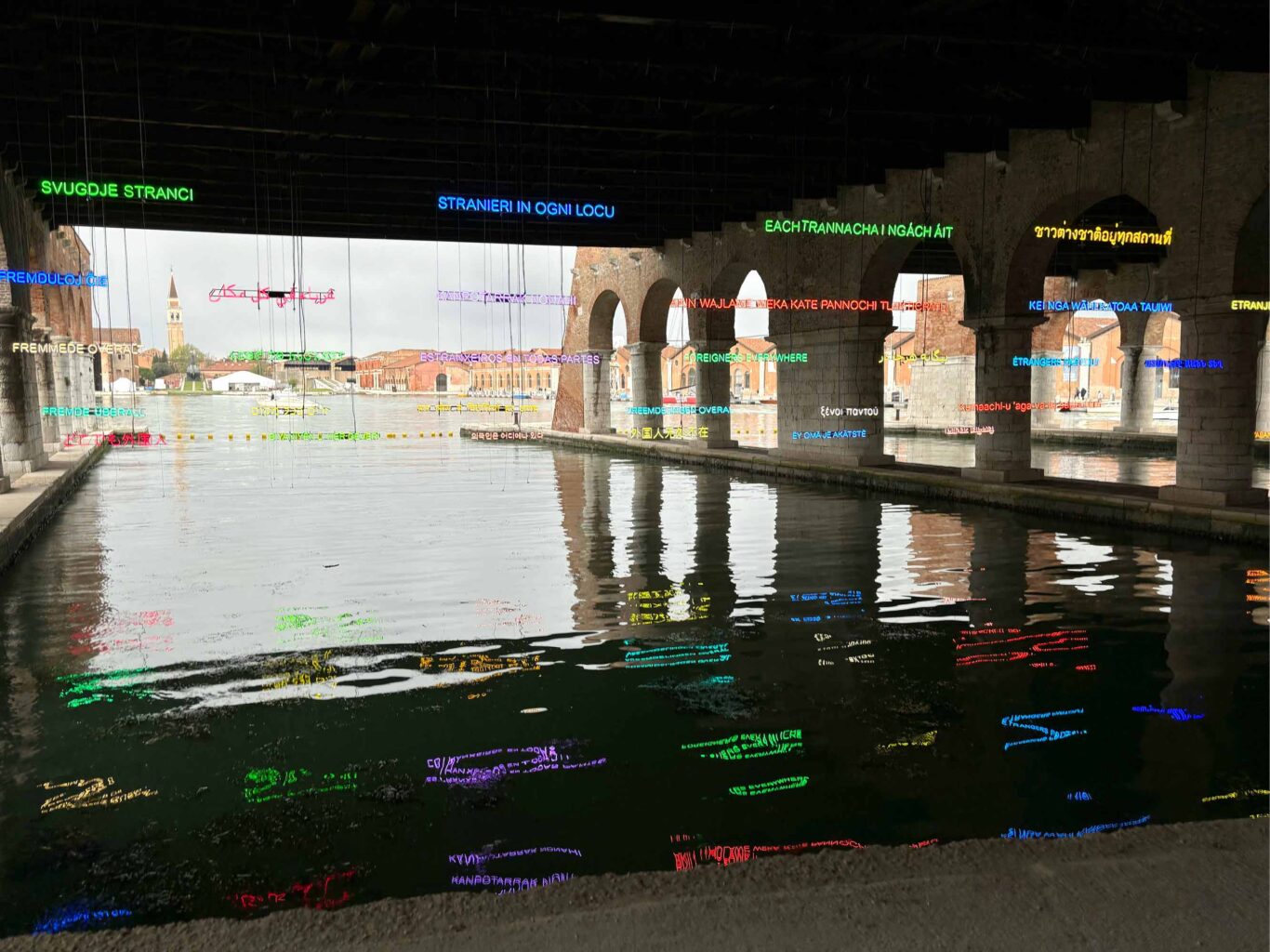

The English title of the Biennale, Foreigners Everywhere, is taken from a work by the feminist art collective Claire Fontaine. Since 2005, it has been using this expression in the form of neon lettering at a growing number of speeches. The two words combine the ambiguity of the foreigner with the universal that connects us, namely, that we are all foreigners to someone else. Foreignness connects and separates us at the same time. The rift of foreignness is omnipresent, unpredictable, and does not only come up where we might expect it. Expected foreignness can even seem superficial in relationship to more specific foreignness. The fact that I feel foreign in an unknown culture, in a foreign city, is a given and a phenomenon of opacity, of a difficulty to understand. We have learned to deal with it; we have tricks and concepts at hand to protect and affirm our own identity through exclusion and marginalization. This is the root of xenophobia. Foreignness in front of your life partner, in front of a close friend with whom you have been friends for over twenty years, and even in front of yourself, on the other hand, is uncanny and transparent. When it occurs, a veil is drawn between me and the foreigner—a transparent border. This form of foreignness is challenging and unsettling, but it is productive and kills xenophobia at its root.

Understood in this way, the concept of foreignness seems to me to be an apt definition of the situation of humanity today. A humanity that is searching for itself beyond convention and outdated traditions, beyond ingrained idioms and phrases. A humanity that falls far behind when it avoids the transparent border and instead takes refuge in the security and clarity of exclusion on the national and local levels.

With this perspective of foreignness, the efforts of identity politics and the narrowing of art as representation for a nation or a group—be it women, queer persons, or indigenous people—can be better classified. Pedrosa’s statement (“Art can’t change the world, but it can change our view of it”) would now read like this: An exhibition as a practice in tolerance and inclusion, but also an exhibition against forgetting, and a call to art history to reorganize itself. No great excitement, but a small, patient step forward. As the Ghanaian writer Ayi Kwei Armah once wrote: “Culture is a process, not an event.”1

Those who miss better-known names in the main exhibition and the national pavilions will find a rich offering of sophisticated accompanying exhibitions, for example, Berlinde De Bruyckere’s archangel sculptures in the Basilica of San Giorgio Maggiore, Pierre Huyghe’s works in the Punta della Dogana, a comprehensive exhibition with the US painter Julie Mehretu in the Palazzo Grassi, or Christoph Büchel, who has transformed three floors of the Palazzo of the Fondazione Prada into a pawnshop—an ingenious staging.

The Venice Biennale runs until November 24, 2024.

Translation Joshua Kelberman

Footnotes

- Eric Otieno Sumba, “Africa Out of Venice,” Frieze, no. 242 (April 2024). Available online: https://www.frieze.com/article/history-of-african-pavilions-at-venice-biennale-242. Sumba quotes Ayi Kwei Armah’s article, “The Festival Syndrome,” West Africa (April 15, 1985): “Culture is a process, not an event. . . . The development of culture depends on a steady, sustained series of supportive activities whose primary quality is not a spectacular extravagance but a calm continuity.”