We children of Prometheus have built human culture with fire and around the fire. Fire refines metals and plastics from Earth materials, and casts them into a thousand forms. Fire gives the modern world light and speed. But is this now coming to an end? Is fire entering a new, more human phase?

Anthropologists believe human beings first sat around a fire around 1.5–2 million years ago. Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania, the cradle of humanity, is the oldest excavated site where fire was used by the earliest humans. Throughout this long stretch of time, fire has been helpfully serving our human culture. Community arose around the fire and, along with it, speech. Around the fire, we had protection, warmth, and light. We could find food with fire and, with fire, preserve it. For good reason, the Greeks saw Prometheus as the forefather of all human culture because he brought the flame from heaven to the Earth. Claude Lévi-Strauss, the French anthropologist, found this heavenly gift of tending fire in the myths of nearly every culture. And in all these stories, it is fire that makes human beings human. Charles Darwin called it the greatest human invention after speech. Fire not only shaped and formed the human community, it was the first tool to completely change the environment. We now call this earth-transforming tool “slash-and-burn” agriculture. The first settlers of America found mostly wide open landscapes and vast grasslands of prairie. The reason for this soon became clear to them: twice a year, the Native Americans drove a fire over the vegetation in order to clear the field for hunting. With fire, cooking begins—what was previously inedible is now worth gathering, and the division of labor begins. The community gains a center with the hearth.

As time went on, various human cultures discovered that fire can be used to bake clay into pottery. The Copper, Bronze, and Iron Ages are named after their advancements in fire technology. Using fire, metals are extracted from rock ores and forged in the flame. So, it’s not surprising that fire is the most important medium and tool of human culture and civilization after speech. Civilization involves domesticating and controlling these fire spirits. Unleashing the power of fire has also eradicated great cultural treasures: the burning of the Ephesian Temple of Artemis in 356 BC, the burning of the Library of Alexandria, the burning of ancient Rome in 64 AD, the great fire of London in 1666, and the burning of the first Goetheanum. Mastering fire has therefore also been a challenge. And now, after 1.5 million years, human beings are releasing the fire spirits from their eons of service. But what will become of these spirits once human culture outgrows them?

“Light the fire! Fire is supreme.” This is how Goethe begins his fire hymn “Chor der Schmiede” [Choral of the blacksmith.] By taming fire, restraining its destructive force, nature became culture, allowing human beings to rise above creation. Is the digital age beginning a fireless dominion?

Fireless Light

In 1879, Thomas Alva Edison invited journalists to his laboratory in Menlo Park, just outside of New York City, to present his latest invention. The unveiling was strangely scheduled for after sunset. Edison’s guests wandered through a forest to Edison’s workshop. Lead-acid batteries were hidden behind the trees, and his first incandescent light bulbs hung in the branches. At a signal, the gloomy forest was bathed in light. He could hardly have demonstrated the dawn of the technological Age of Light more impressively. The light bulb has become the epitome of modern times and the technological sovereignty of the human being—fire, trapped in a glass bulb, can now illuminate a table, a room, and even a whole soccer field at the touch of a button. Only a small amount of burning fire is collected in the lightbulb’s filament to become light, and yet this invention has enlightened and illuminated the whole world.

As a child, when I didn’t want to go to school, I would hold the mercury tip of the thermometer on the lightbulb of the bedside lamp until the column rose to feverish heights. Now, however, fire has been freed from the glass bulbs. Modern LED lights provide warm light with the same color temperature as incandescent lamps (2700 K) and, with a 97% CRI (Colour Rendering Index), they are indistinguishable from incandescent lamps or halogen lamps in terms of color fidelity. Significantly, these flameless lights can also now illuminate the color-sensitive tones of the human face in true color. (We’ll not go into the questions of more subtle effects here.) The 12-volt halogen bulbs, which will be withdrawn from the EU markets, are a kind of last of the Mohicans of the old light bulbs. From candles to oil lamps to gas lamps, fire has been increasingly domesticated and, ultimately, locked up within a glass bulb. Now, with LEDs, fire is vanishing from lighting altogether. LEDs can produce “warm” light, but not from fire—there’s now a cold “warm” light streaming out from millions of LED lights everywhere.

Fireless Motors

And it’s the same in the field of transportation. First, we had steam boilers that initiated modern mobility on water and rails—the Age of Machines. Then, the internal combustion engine came along at the beginning of the twentieth century. It was small and light and made it possible to drive two- and four-wheeled vehicles on the road. Now, movement was not only fast; it was free and individual. The prosperity and desire for freedom of the twentieth century would have been inconceivable without the combustion engine. Turbochargers and intercooling squeezed more and more force out of fire at ever higher pressures. “Nobody wants the last drop of oil anymore,” predicted geologist Colin Campbell in his book Ölwechsel [Oil change]. The changeover to electric cars now gaining momentum seems to prove him right. In a few years, the Netherlands will no longer permit combustion engines, and in Norway, half of all new vehicle registrations are already electric. In ten years, combustion engines will be in the minority, and in twenty years, they will have all but disappeared. Fire will then also be a thing of the past in transportation. The first small hydrogen-powered aircraft and the latest projects from the two major commercial aircraft manufacturers suggest that fire has no future in the air either.

First, the wild flame that, as fire, creates new fire. Then, in the glass, a burning without burning. Now, light without warmth, a light that isn’t fire.

Fireless Factories

During my studies in the Ruhr region of Germany, the sky often glowed red in the evening. The factories of Thyssen and Krupp pushed their huge steel profiles and shafts up out of the factory buildings. But this time is also coming to an end. Today, it’s not just plastic that is being injected and molded into complex shapes with 3D printers. Metal can now be “printed” without heat or fire. A laser beam passes over a wafer-thin layer of metal dust and melts the relevant areas. Metal layer after metal layer is applied and liquefied by the laser. The molds produced in this way are much more complex and use less material than solid casting. So, fire seems to have had its day in factories, too.

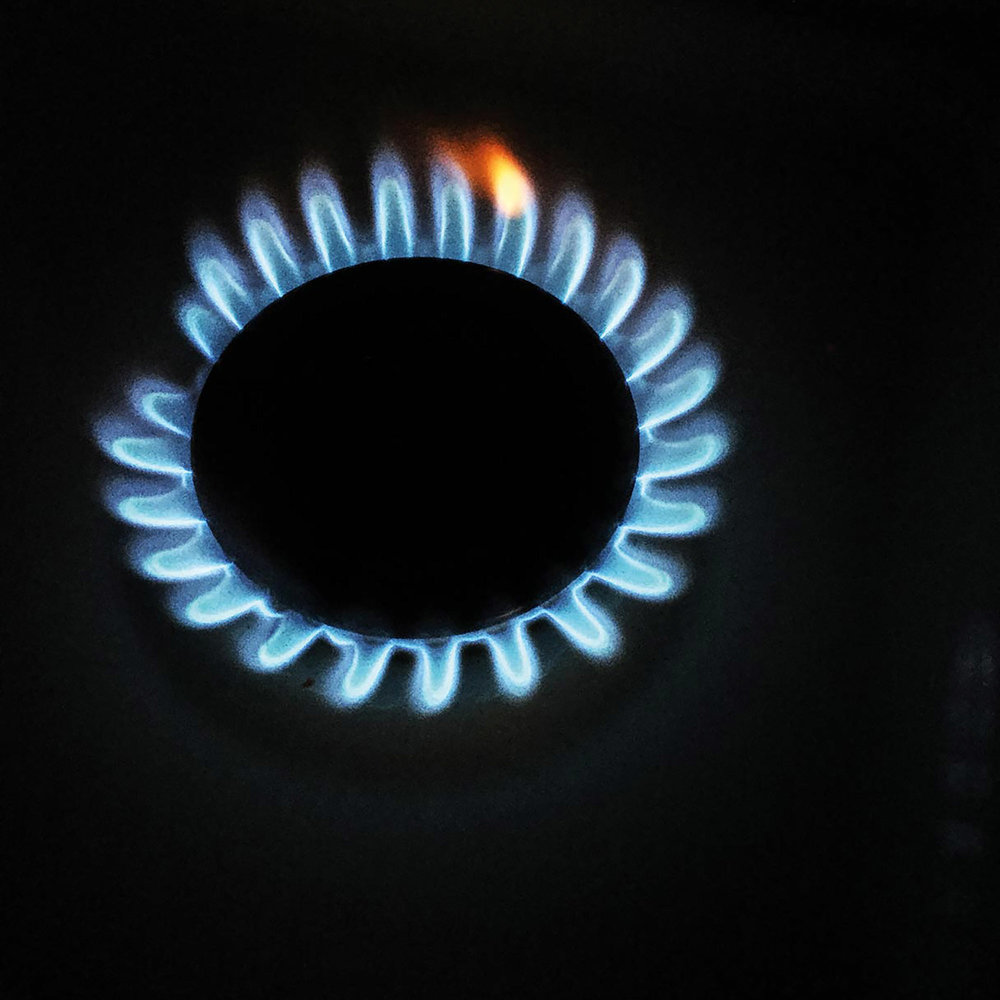

The flame is even moving away from its traditional place in household heating systems and ovens. As a young boy, I used to sit in front of our oil burner in the cellar and watch the fire in the combustion chamber through the little viewing window. First, it made a rhythmic clicking (the ignition spark), then the oil splashed in, and the fuel ignited in wild tongues of fire. Today, the burner has been replaced by the heat pump, which uses the hot water from solar collectors or the ground to provide hot water for underfloor heating or faucets.

First, the scorching heat, then the fire on the stove. Nowhere is the home so maternal. Now, the heat hides behind the glass on a sensor or voice command.

A path of life that begins in the sun then flows and ends in fire. Its warmth and light allow plants to grow. Wood, gas, coal, and oil—substances of a former life, some quite old, some younger—all store solar energy, and when ignited with fire, this solar power blazes forth anew. The solar process that made the plants grow and flourish now runs its course in reverse. And just as the sun gives light and warmth to the Earth, every fire is also a union of light and warmth. Heat predominates in the embers, light in the flame, yet a fire is always both.

Perhaps this is why we can never get enough of fire, because the combination of light and warmth is at the core of the human soul. Only when the two come together does the soul become the soul. What is warmth in nature becomes a force in the soul that, like heat, can permeate everything, and when it is truly authentic, it is limitless and unbounded. Even the best insulation will not stop this power of warmth in the long run. In the soul, warmth becomes love. For our love to become true, we cannot love one person but not another. Love is universal by nature. In warmth, everything becomes one whole, because warmth and its higher sister, love, are united. Light has a different character; it has the ability to separate, differentiate. With light, the world becomes individualized, particular. Human thinking, this organ of light in the human being, creates in spirit what the sun fulfills in the physical. Coming out of error, out of the soul darkness of a false or even deceitful idea into the spiritual experience of light, is one of the happiest moments of life. But what does it mean when fire—this great representative of the union of warmth and light, of love and knowledge—what does it mean when fire ends its service?

The Resurrection of Fire

In his anthropological research, Rudolf Steiner repeatedly drew attention to one of the most fundamental observations of life: a force that has exhausted itself, that completes its work, is not lost or used up like raw material; rather it can now become active on a higher level. We observe this in every flower. As it grows, it forms leaf after leaf. At the end of its vegetative phase, when the leaf growth has been fulfilled, then color, fragrance, and soul emerge all at once in blossom and fruit—the plant reaches a new stage. In human beings, we see life’s law of energy conservation in the change of teeth and with sexual maturity. Once the solid enamel of the permanent teeth is formed, this hardening force is now available for a kind of mental chewing. And once sexual maturity is reached, the forces that developed the body can now unfold on a higher level as empathy and idealism.

If fire has now fulfilled its duty and been released from its years of servitude, perhaps it is now equally true that the ability of fire to unite warmth and light, its power to integrate diverging forces, can now become free and work upon a higher level. At times in human history, the scale has tipped more towards one of these two forces, more to the side of empathy and warmth or more to the side of light and the bright clarity of ideals. In early Christianity, mercy and a will to love emerged. A millennium later, in Arabic culture, the ability to analyze and calculate dominated. It was the Arabs who gave many stars their names. We can probably even distinguish these different periods in every biography when either warmth or light predominates. And it seems that sometimes it is precisely the absence of warmth that stimulates an awakening in the light of the mind.

But today, what counts is not that warmth and love follow one after the other, but that they come together, united. As soon as one or the other dominates one-sidedly, we encounter some kind of harm or imbalance. The tale of Parzival is, perhaps, the first great telling of the marriage of light and warmth. It is not enough for the young knight to just have pity for Amfortas and his wound—not enough only to have compassion for the ailing Grail knight. Parzival must also understand; he must seek knowledge. Love without knowledge means as little as knowledge without love. In his book Meditation as Contemplative Inquiry,1 Arthur Zajonc describes the fundamental experience of meditation as the belonging together of knowing and loving. One can only know what one learns to love, and one can only love what one wants to know.

Now, when fire ends its service—no longer illuminating, driving, and warming the human world—this power of integration, this sun being, may rise to a hitherto unknown degree, to then be able to resurrect in human beings as a community of warmth and light, of love and knowledge.

Julian’s Call to the Spiritual Sun

Often, when humanity takes a mighty step in its development, it sings a great song to the sun. The pharaoh Amenhotep IV, who called himself Akhenaten, “Son of the Sun,” sang about the unity and divinity of the sun around 1350 BC: “Whenever you are risen upon the eastern horizon, you fill every land with your perfection. You are appealing, great, sparkling, high over every land.” 2 It is the “one” sun that shines above all, like the “one” God. When the Middle Ages transitioned into modern times, when human awareness of self was beginning to awaken, Francis of Assisi sang of the sun as God’s highest work. And between these two sun songs, in the fourth century after Christ, when antiquity and its mythical foundation were fading, and Christianity was taking its place, the Roman emperor Julian the Apostate wrote his hymn to the sun god Helios. At this same time, the Oracle of Delphi, having shaped the destiny of Europe for a thousand years, gave the Emperor Julian its last prophecy, the news of the moment’s turning point in time: “Go tell the king the magnificent hall has fallen: Apollo has a home no more, no laurel that foretells, no talking spring. The water that once spoke is heard no more.”3 On this threshold of pre-Christian twilight and Christian dawn, Julian now writes his hymn to the sun, Oration upon the Sovereign Sun. “It would be better to be silent, but I will speak” is how he chooses to express his thoughts on the place and appearance of the sun in his solar hymn.4 Where Plato writes just the reverse, that one may continue to speak, but he will not, Julian turns it around and speaks thus of the sun: it is not in the middle of the planets, but beyond them in the unstarry region, and, from there, a threefold blessing of three graces pours down upon the Earth.

Like Rudolf Steiner does years later, Julian emphasized that the visible sun is only a shadow of the actual sun, the spiritual sun, which lies beyond the stars. The graces of this original sun can be seen in the seasons, as we understand Julian here. But what are the graces? They are what the seasons upon the Earth give to us as three solar qualities. In summer, the sun bathes the Earth in light. In winter (more difficult to understand), the sun sinks life into the Earth. Just as the exhausted organism is renewed and regenerated in sleep each night, endowed with new life, so it is for the Earth during winter. The sun sinks life into the Earth, that then unfolds in spring and summer. The third gift of the sun is warmth, mainly felt during the transitions of spring and fall. What unfolds in nature as warmth, light, and life from the sun corresponds to what is spiritual warmth, spiritual light, and spiritual life in the human soul: love, knowledge, and freedom.

If now, the fire dies down, if this inverse solar procession now dies away in our culture, then, perhaps, it is the sign that this unified empathy and knowledge, love and wisdom, this meditative attitude may be offering a new life within the human being. The sun, as fire in the earthly world, has gone through a kind of death. In human beings, as a unified whole of love and knowledge and freedom, the sun can become a new sun. The sun Julian the Apostate speaks of in his hymn to the sun, the spiritual sun beyond the stars, finds its mirror, its answer in the rebirth of fire in the human soul.

The central idea of this article is thanks to conversations with Georg Hasler.

Translation Joshua Kelberman

Footnotes

- Arthur Zajonc, Meditation as Contemplative Inquiry: When Knowing Becomes Love, (Lindisfarne Books, 2009).

- William Kelly Simpson, ed., The Literature of Ancient Egypt, 3rd edn. (New Haven: Yale Univ. Press, 2003).

- [This oracle is considered to be a fabrication. Cf. Philostorgius, Church History, translated by Philip R. Amidon (Atlanta, GA: Society for Biblical Literature, 2007), p. 88—Trans. note.]

- Emperor Julian, “Upon the Sovereign Sun,” in C. W. King, trans., Julian the Emperor (London: George Bell, 1888), p. 283.