Marginalia on Rudolf Steiner’s Life and Work 26

In his Autobiography, Rudolf Steiner wrote in detail about a personality who would later turn both against him and Anthroposophy: the “liberal politician” Dr. Heinrich Fränkel (1859–1939), “an adherent of Eugen Richter and politically active in the same spirit.”1 Richter represented the Deutsche Freisinnige Partei (German Liberal Party) which was critical of the government and economically liberal. In 1893, he founded the even more leftist Freisinnige Volkspartei (Liberal People’s Party).

Fränkel, who came from a Leipzig merchant family, gained his doctorate with a thesis on Daily Working Hours in Industry and Agriculture with Particular Reference to the German Situation (Leipzig 1882). For a while, he was employed as a secretary in the Chamber of Commerce, probably in Berlin. In Weimar, where he relocated with his wife Anna Ende in the 1880s, he launched, in 1889, the more bourgeois Verein für Massenverbreitung guter Schriften (Society for the Mass Distribution of Good Literature, 1889–1894) as a means of fighting against the “trashy novel” culture. It was then that he first met Rudolf Steiner. “A brief acquaintance [that] ended because of a ‘misunderstanding,’ but it was one I happily recall often. Fränkel was extraordinarily likeable in his own way. As a politician, he was energetic and strong-willed, and he was convinced that, with goodwill and rational insight, human beings can be aroused to enthusiasm for the proper, progressive way in social affairs. But his life was a long string of disappointments. It’s unfortunate that I, too, ended up disappointing him. During our acquaintance, he worked on a brochure that he hoped to distribute on a large scale.”

With this brochure, which was published under the pseudonym Ghibellinus with the title “Emperor, be firm” (Weimar 1891), Fränkel intended to convince “those around the Kaiser of the dangers he saw coming,” that is, the “future consequences of an alliance between big industry and agriculture, which was then in an embryonic stage in Germany. In his opinion, it was guaranteed to result in disaster.” But he “accomplished nothing at all; he came to realize that the party to which he belonged and for which he worked was not strong enough to support his intended actions.”

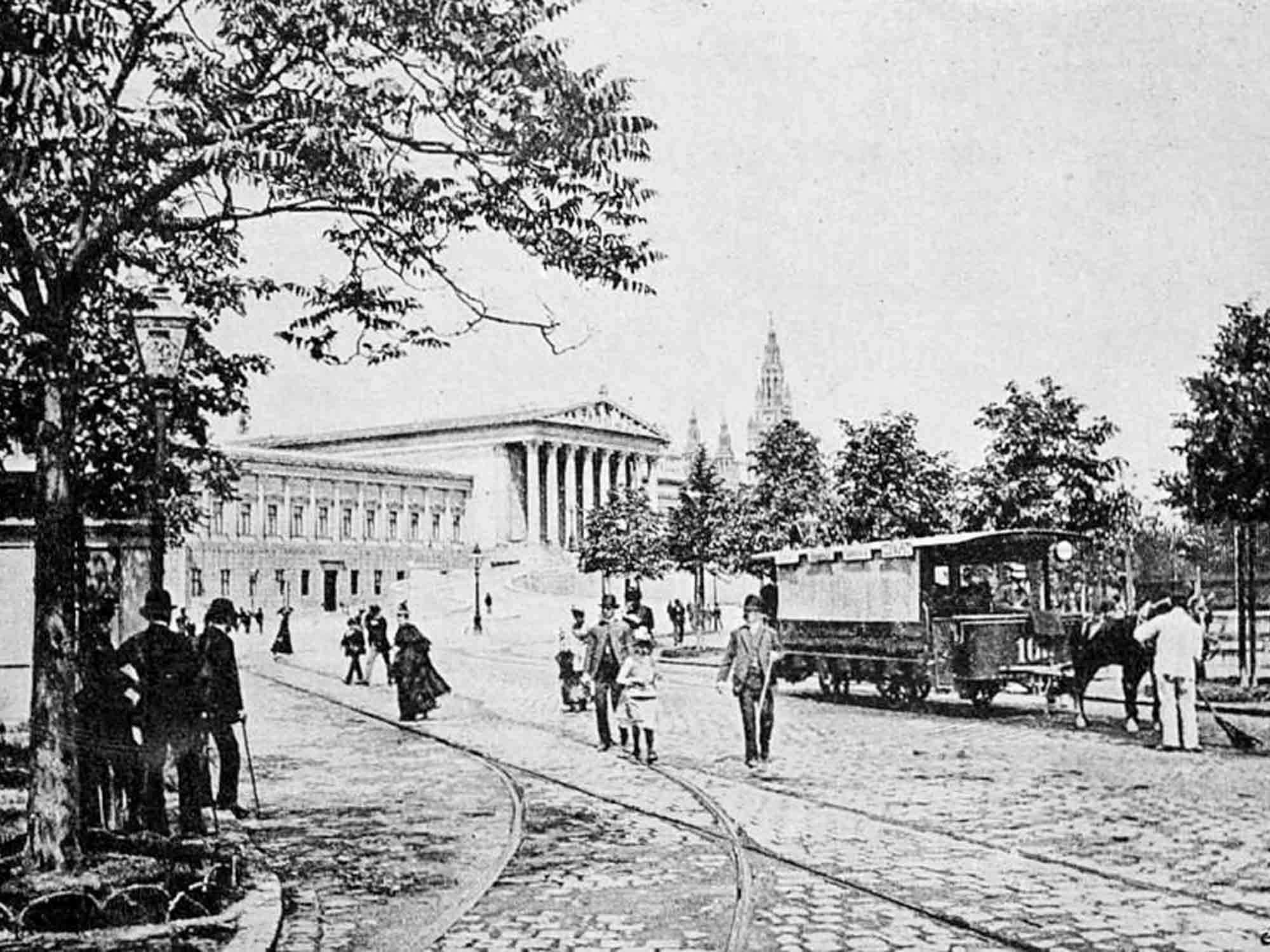

In the summer of 1892, Heinrich Fränkel went to Vienna to promote his idea of launching a German national paper, and possibly breathe new life into the Deutsche Wochenschrift (German Weekly), which Rudolf Steiner had edited for a few weeks in 1888.2“Through that paper, he hoped to create a political stream that would lead his political activity out of the current liberalism into a more national, free-thinking direction. He thought that he and I could work together on this. But that was impossible. I could not do anything, even to revive the German Weekly. And the way I explained this to him caused misunderstandings that soon ruined our friendship.”

Fränkel’s introduction of Rudolf Steiner to his family, “a wife and a sister-in-law who were very charming” as well as two daughters, would, importantly, impact on Rudolf Steiner’s life because it was due to this acquaintance that he “met yet another family” – the Eunike family.

In August 1892, shortly after Rudolf Steiner had moved in with the Eunike family in Prellerstrasse, a misunderstanding between the two families regarding a private arrangement ended their friendship. From what can be discerned from a letter written by Heinrich Fränkel, Rudolf Steiner had taken an invitation, extended in earnest, for a joke, and made other plans for that evening. He apologized later in a letter, which has not been preserved, to Anna Fränkel. Her husband responded to that letter.3

Nothing more is known of any further intercourse between the families, other than a strange letter Anna Fränkel wrote on November 19, 1914 “to the leaders of the Theosophical Federation,” asking “To what kind of thinking is your activity consecrated?” She then goes on to express her hope that as an international federation, it would work above all toward “making the fate of our imprisoned, brave troops more humane.” She was referring to the destiny of the German prisoners of war.

The Fränkel family then lived for many years in Nikolassee near Berlin. In 1918, they changed their name to “Frenzel”. Heinrich Frenzel-Fränkel continued to write prolifically, producing many more brochures. Politically, he moved increasingly toward the right. For a while, he worked for the National Liberal Party and after World War I for the Deutsche Volkspartei (German People’s Party). Shortly before the German politician Matthias Erzberger was murdered, Fränkel had attacked him in a pamphlet.4 Soon after, he agitated against the liberal politician Walther Rathenau. The Association for the Prevention of Antisemitism (Verein zur Abwehr des Antisemitismus) wrote in its newsletter5 that Erich Ludendorff had provided the “baptized Jew” Frenzel, who “now conducts himself like a particularly fervent antisemite,” with the material for this “sleazy paper.”

From 1925 to 1933, Fränkel/Frenzel was editor of the newspaper Fränkische Wacht. Für Christentum und Deutschtum im protestantischen Geist (Franconian Watch. For Christianity and Germanity in the Protestant spirit). He lived near Nuremberg at the time. How harmful his activities were at the time is apparent from a letter Ernst Lippold, whose family were neighbors of Heinrich Frenzel for a long time there, written to Emil Bock on January 4, 1959. Lippold pointed out that Frenzel had “used Rudolf Steiner’s seeming inconsistencies to work against him.”6 In parentheses he added, “He also had a disastrous effect on the insane Krieger before he shot Dr. Carl Unger in Nuremberg in 1929.”7 – A remarkable circle closes here from the breakdown of a friendship in Weimar to the devastating effect on a mentally instable person who shot a leading anthroposophist!

The Jewish-born, protestant Christian, and fervent antisemite Heinrich Fränkel died as Heinrich Israel Frenzel in 1939, in a protestant hospital (Elisabethenstift) in Darmstadt, Germany.

Translation Margot M. Saar

Image Ringstrasse in Vienna with Parliament building, ca. 1890. Photo by Victor Angerer

Footnotes

- All following citations are taken from Rudolf Steiner, Autobiography, GA 28, Great Barrington 2006, translated by Rita Stebbing (revised), p. 147f.

- Cf. “Rudolf Steiners kurzes Gastspiel als Redakteur der Deutschen Wochenschrift” (Rudolf Steiner’s Brief Spell as Editor of the German Weekly) in Das Goetheanum 25–26/2019, and Martina Maria Sam, Die Wiener Jahre, (The Vienna Years) Dornach 2021, Chapter 8.3. Fränkel thought it “highly desirable,” as he wrote in a postcard of June 23, 1892, that Rudolf Steiner should come to Vienna; cf. Rudolf Steiner, Sämtliche Briefe 2, Basel 2023, p. 391.

- Ibid., p. 396f.

- 4 “Erzberger der Reichsverderber!” (Erzberger, Spoiler of the Reich), Leipzig 1919.

- Issue 13–14/1922 of July 17, 1922.

- In 1925, for instance, he wrote a venomous article in Fränkische Wacht, targeting the Christian Community among other things. Steiner, he complained, had “not a trace of what we call religious or moral feeling,” adding that “his standard statement, which I must have heard him utter more than fifty times, was ‘My only principle is not to have any principles.’” (Issue 14/1925)

- Emil Bock’s estate in the Christian Community’s central archives in Berlin. – The mechanic Wilhelm Krieger had been a member for many years and spent periods of time working on the First Goetheanum. He had struggled with mental illness for some time. On January 4, 1929, he shot Carl Unger (1878-1929) during a lecture Unger gave in Nuremberg. Albert Steffen wrote in his obituary, “Questioning of the perpetrator confirmed that he was insane and had suffered from paranoia for years.” In: Was in der Anthroposophischen Gesellschaft vorgeht, 2/1929.