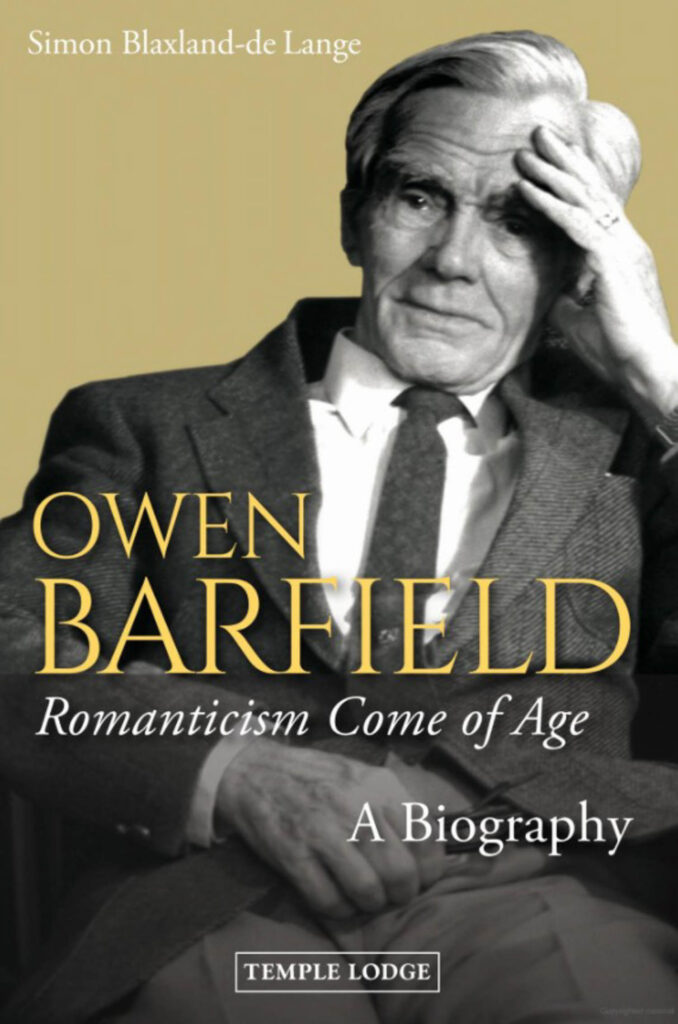

Who was Arthur Owen Barfield? Rudolf Steiner’s foremost interpreter in the English-speaking world, some might say; the «wisest friend» of C. S. Lewis, «first and last» member of the Inklings—that massively influential, 20th century group of intellectuals and authors which also included J. R. R. Tolkien among its ranks; a scholar of Samuel Taylor Coleridge and Romantic philosopher in his own right, others might say. No doubt, Barfield would appreciate these acknowledgements, but when—in 1991, six years before his death in 1997—he sat down in his Sussex home with his biographer, Simone Blaxland-de Lange, he insisted that only the most spiritually salient contours of his life be communicated to posterity. It was in the form of ‹psychography›, or ‹biography of the soul›, that Barfield intended his story to be told, a distillate of his life shone through with the archetypal—an imagination.

Blaxland-de Lange attempts to honor Barfield’s wishes in ‹Owen Barfield, Romanticism Come of Age: A Biography› and goes even further: by structuring the book in accordance with the review process that—per Steiner’s indications—Barfield’s soul-spiritual individuality would undergo over a period of 33 years beginning with his death in 1997. In doing so, Blaxland-de Lange aspired to actualize the potential for us to «follow and form a relationship to the unfolding present destiny of a soul that has lived on earth and convey this knowledge to one’s fellow human beings.»1 Psychography thus becomes a means of communion, a means of «seeking guidance from this now super-earthly being for what we may now ourselves accomplish.»2 Blaxland-de Lange concludes the book by calling on others to carry this effort further; I attempt to do so in this two-part essay, guided by these questions: «Where is the individuality of Arthur Owen Barfield in late 2022 and what guidance might this being have for us today?»

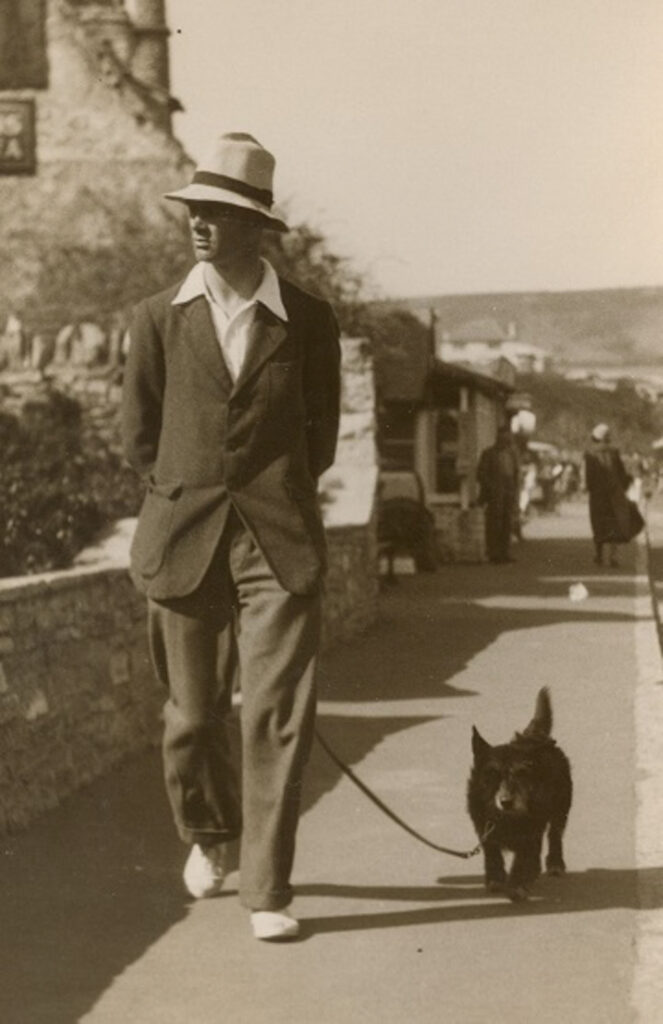

Barfield was born November 8th, 1898, in London, England and died almost 25 years ago in Forest Row, England on December 14th 1997; he had recently celebrated his 99th birthday. If, following Blaxland-de Lange, we work with Steiner’s indication that «the soul of the person who has died lives in a state of conscious awareness and in a backwards order through the entire context of what has been experienced in sleep,» a process that typically lasts one-third of the individual’s lifetime, we end up with a total of 12,065 days or 33 years.3 Subtract the number of days that have transpired since this process began (writing on October 11th, 2022) and we arrive at about 3,000 days of review remaining. Finally, if we multiply this number by 3—and get 9,000 days—we can then calculate for a rough approximation of the period of life that Barfield’s individuality is currently reviewing by adding that number of days to his birthdate. We arrive at July 1st, 1923—a significant year, it turns out. Barfield was 24, going on 25, and had just married Maud Douie (on April 11th, 1923) whom he met while touring Cornish towns and villages performing with the English Folk Dance Society. The year prior—1922—Barfield’s childhood friend and—eventually—fellow Anthroposophist, Cecil Harwood, had joined in on the dance tours and met his wife, Daphne Olivier. It was Olivier who—having been recently ignited with enthusiasm for Steiner’s ideas on education—introduced Barfield and Harwood to Anthroposophy. «Through her, Harwood and Barfield began—‹rather skeptically›, as Barfield records—attending some weekly lecture-readings which George Adams (then George Kaufmann) was conducting.»4 Thanks to a diary entry written by C. S. Lewis, we can surmise about when Barfield’s skepticism began to lift: as Blaxland-de Lange writes, Lewis «had been vehemently opposed to any trace of Steiner’s influence on his friends (i.e. in particular Barfield and Harwood) from the time of their first encounter with his ideas in the summer of 1923. On July 7th, 1923 he had recorded his thoughts on the matter in his diary:»

Harwood told me of this new philosopher, Rudolf Steiner… [He] seems to be a sort of panpsychist, with a vein of posing superstition, and I was very much disappointed to hear that both Harwood and Barfield were impressed by him. The comfort they got from him (apart from the sugar plum of promised immortality, which is really the bait with which he has caught Harwood) seemed something I could get much better without him.

Blaxland-de Lange, Owen Barfield: Romanticism Come of Age: A Biography, 157; my emphasis

It was around this time that seeds were sown for the ‹Great War› waged between Lewis and Barfield—an epistemological debate that reached its highest pitch between 1927 and 1929. A central issue of this debate was the status of imagination—could it serve as a «vehicle for truth»?5 Barfield’s answer was a lifelong, resounding ‹yes›, for it was something he knew from experience. This insight—which he achieved before discovering anthroposophy—was also what ultimately gave him confidence in Steiner. But Lewis would have none of it. And though Lewis learned a great deal from his intellectual battles with Barfield, and vice versa, he never budged on the status of the imagination. As Barfield himself put it, Lewis «accepted the conventionally scientific basis of knowledge and that all real knowledge depended on scientific evidence drawn from sense experience. [He] would not admit that the kind of experience that came through imagination had anything to with knowledge of reality.»6 Those familiar with anthroposophy will likely recognize Lewis’ position as tantamount to what Steiner called ‹materialism›, a worldview—still dominant today—that limits meaning exclusively to the human subject. A chasm yawns between the meaning-seeking human soul and the cold indifference of a world reduced to a manipulable collection of objects. But, in continuity with Romantic poets and philosophers before him, Steiner insists that the imagination can be cultivated as a supersensible organ of perception; the threshold of that abyssal chasm between subject and object can be crossed; reunion with the spiritual forces weaving the phenomenal world can be achieved. But, perhaps understandably—for the first half of the 20th century was dismal indeed—the ‹spiritual science› of Anthroposophy was not something Lewis could take seriously. Maud, Barfield’s wife, was also opposed to Anthroposophy. After joining the Anthroposophical Society in 1924—the year after their wedding—Barfield remembers a time when

members of the Society were coming to see me, and … she didn’t think they always had as much sense as she had! She continued to be strongly averse to Anthroposophy … but I felt I couldn’t give it up or cease to interest myself in it … It was a kind of sword through the marriage knot, right through, almost right through; though we had enough in common to get on pretty well together.

Blaxland-de Lange, Owen Barfield: Romanticism Come of Age: A Biography, 30-31

A mutual love of music and dance—the context in which their relationship began—bound the two together in deep ways, but Maud was rooted in the perspective of her Scottish church and found Steiner’s confident insistence on spiritual facts objectionable. Unlike Lewis, however, Maud seems to have had a change of heart in later years.«And right at the end,» says Barfield, «I was astonished to learn that she had applied to join the [Anthroposophical] Society… Kind of making amends… she had taken this step to join, and that did make up for something. It was rather touching.»7 Barfield’s astonishment reflects the fact that, throughout their married life, Maud’s attitude towards anthroposophy, like Lewis’, was hostile. Zooming out now, I ask: «What, in the vein of psychography, is most salient about Barfield’s life in summer of 1923?» Three developments stand out most: Barfield and Maud were recently wed; Barfield opens himself to anthroposophy; Barfield’s intellectual conflict with both Lewis and Maud, however nascent, begins. The crucial question sounding forth from these features is: What experience granted Barfield insight into the imagination such that, despite his personal conflicts with Lewis and Maud, he remained committed to its truth-value throughout his life?

An important element of Barfield’s biography is that he was—as people today often say—‹embodied.› His family was musical and, when the many extended relatives got together for Christmas, they «always finished up dancing Sir Roger de Coverley, which is a folk dance.» «It always stuck in mind,» he continues, «that when I saw this I thought that the more there is of that kind of thing [folk dancing] the better and that I’ll try it.»8 And try it he would, for the bulk of Barfield’s early twenties was spent dancing with the English Folk Dance Society. During his high school years Barfield managed to opt out of the school’s compulsory sports participation and dedicated his time to gymnastics instead. The school apparently cared little for this ancient art of physical exercise, «so in a year or two,» says Barfield, «I became practically the senior gymnast in the school—not that I was very advanced either but their standards were so low!»9 Interestingly, Steiner reports in his ‹Speech and Drama› lectures that ancient Greek gymnastics unfolded from «the realization that the will lives in the limbs. And the very first thing the will does is to bring man into connection with the earth, so that a relationship of force develops between man’s limbs and the earth.»10 According to Steiner, the main exercises were

founded on upon man’s connection with the cosmos. Starting from this relationship he has to the cosmos, man is in these exercises perpetually forming as it were another relationship, a relationship of gesture; and in gesture the force, the dynamic of the human being himself is present. But men had the very same feeling in those earlier times about the revelation of the human being in speech.

Steiner, Speech and Drama, 53.

Because thought—in modernity—«is generally lifted out of speech, abstracted from it,» Steiner insisted upon gymnastics as a necessary foundation for training in dramatic art. Through a modified form of these exercises, performers could practice embodying gestures which intoned the archetypal human form (as dynamically inscribed by the cosmic imagination) and reconnect these substantial realities with their speech. In doing so, Steiner says,

we shall be on the right path for discovering how gesture can come to the help of the word in dramatic art; for there is, in fact, no justifiable gesture for the stage that is not a kind of shadow-picture of some one of the five exercises of Greek gymnastics. That is, however, the other pole. The one pole is speech itself, the form of speech.

Ibid.

The same intelligibility inhering in meaningful speech shines out from the human body as archetypal form. By tending to the pole of the will, gymnastics helps bring abstracted thought «back down again into speech» with the ultimate aim of addressing «the need for the forming of the word to become in the actor a complete matter of course, so that it takes place in him instinctively.»11 Steiner’s aim for such training is nothing less than a renewed, but this time consciously experienced, recognition of the human form as the image of the cosmos—a living imagination woven by the cosmic Word. For Steiner, the highest potential of dramatic art and poetry is to be the conscious continuation of this cosmic creativity. One might surmise that Barfield’s practice of gymnastics imbued him, however unconsciously, with insight into the cosmic meaningfulness of embodiment. As for his capacity to be receptive to something like cosmic creativity, an ecstatic memory from his time Morris Dancing after 1919 attests:

I remember having a vivid experience at the end of one of the movements. You stand there, arms going up and down in one rhythm and your feet tapping in another—and I had a very strong experience of the music flowing through me, so to speak. I was motionless, but the music was flowing through me. It was very strong.

Blaxland-de Lange, Owen Barfield: Romanticism Come of Age: A Biography, 22.

As Philip and Carol Zaleski suggest in their wonderful book on the Inklings—rightly, I think—Morris dancing «opened to him a new realm of quasi-mystical inner experience, in which music served as his daemon or psychopomp.»12 And though gymnastics and dance may have done much to fortify Barfield’s inner life with the incommunicable meanings of music—visitations, perhaps, from worlds of spirit—it would not be enough to carry him across the abyssal threshold of the age; he would need poetry for that.

Footnotes

- Simone Blaxland-de Lange, Owen Barfield: Romanticism Come of Age: A Biography (Temple Lodge Publishing, 2021), 6.

- Blaxland-de Lange, Owen Barfield: Romanticism Come of Age: A Biography, 312.

- Blaxland-de Lange, Owen Barfield: Romanticism Come of Age: A Biography, 6.

- Blaxland-de Lange, Owen Barfield: Romanticism Come of Age: A Biography, 26.

- Blaxland-de Lange, Owen Barfield: Romanticism Come of Age: A Biography, 181.

- Blaxland-de Lange, Owen Barfield: Romanticism Come of Age: A Biography, 181.

- Blaxland-de Lange, Owen Barfield: Romanticism Come of Age: A Biography, 31.

- Blaxland-de Lange, Owen Barfield: Romanticism Come of Age: A Biography, 19.

- Blaxland-de Lange, Owen Barfield: Romanticism Come of Age: A Biography, 22.

- Rudolf Steiner and Marie Steiner-von Sivers, Speech and Drama (SteinerBooks, 1960), 52.

- Steiner, Speech and Drama, 188.

- Philip and Carol Zaleski, The Fellowship: The Literary Lives of the Inklings: J.R.R. Tolkien, C. S. Lewis, Owen Barfield, Charles Williams (NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2015), 106.

Much food for thought and a great wish to read these books I came across! Thank you!