Marginalia on the Life of Rudolf Steiner, Number 27.

While in Weimar, Rudolf Steiner maintained a friendship with the Bock family. He was probably introduced to them in October 1890 by the Danish writer Rudolf Schmidt because, like Schmidt, the engineer and brickworks owner Otto Bock (1850–1913) was originally from Copenhagen. Rudolf Steiner helped Bock with his book on brickworks as an agricultural and independent business (Berlin 1893). The book has the following dedication: “To his dear friend Dr. Steiner with thanks for his kind support, the author, Weimar April 24, 1893.”

Rudolf Steiner’s relations with the family were so close that he was even invited when the sister of Emilia ‘Mila’ Bock (1865 – after 1917) got married in May 1894. Rudolf Steiner initially declined the invitation because the wedding would be just before the annual Goethe Festival which was “for us Weimar Goethe folk, the most exhausting moment of the entire year.”1 However, as a note in Mila Bock’s hand reveals, Steiner “did come to the wedding after all and gave a beautiful speech. M.B.” Rudolf Steiner himself said of this speech, “[…] I attempted to do my duty, which was based on my role as a frequent visitor to the bride’s home. Thus, I spoke of the delightful experiences guests might anticipate in that home. I spoke only because I was expected to, and it was also expected that I would say the ‘appropriate’ things for that occasion. Consequently, I took little pleasure in my role.”2

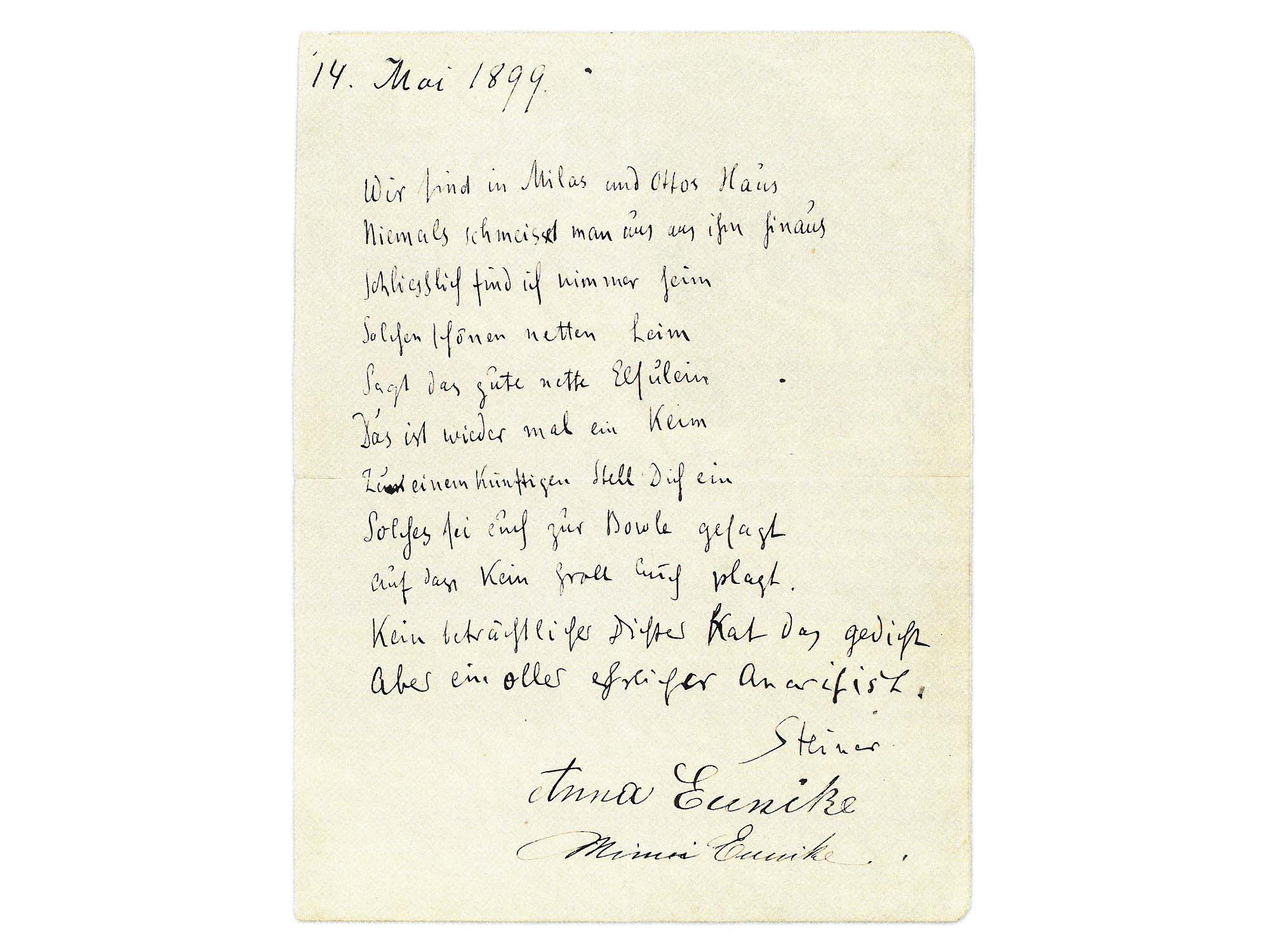

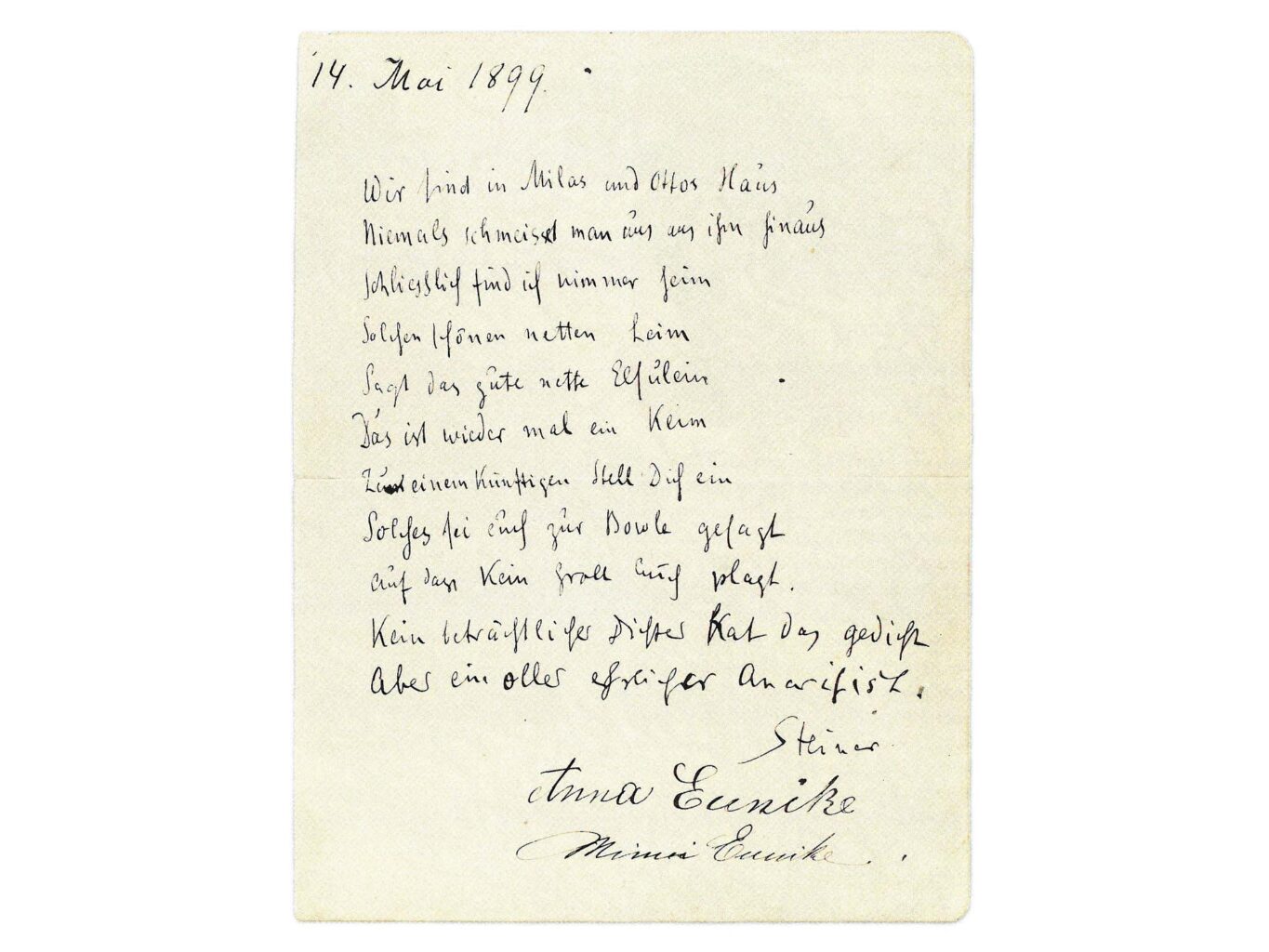

In 1896 the Bock family moved to Berlin, as did Rudolf Steiner and Anna Eunike shortly thereafter. The families stayed in close contact, celebrating festivals such as Christmas and the New Year together. A “Punch Song” in Rudolf Steiner’s handwriting has been preserved from that time:

We’re in Mila and Otto’s house,

No one ever throws us out,

I’ll never find such a home again,

Such warm togetherness

As dear little Elsie says. 3

Which gives us cause anew

For yet another rendezvous

This I must tell you with the punch

So you don’t have to bear a grudge:

No prominent poet has written this

But an old and honest anarchist.

Steiner Anna Eunike Minnie Eunike 4

When Anna Eunike and Rudolf Steiner were married on October 31, 1899, Otto Bock was the best man, alongside John Henry Mackay. In the following years, Mila and Otto Bock occasionally attended the Literary circle of Die Kommenden. It can be assumed that their contact petered out gradually with Rudolf Steiner’s growing engagement with theosophy.

It was not until much later, in February 1917, that Mila Bock wrote to their old friend again. Her letter reflects, in a special way, how early friends followed Rudolf Steiner’s ongoing path. „Dear Dr. Steiner, it will strike you like a greeting from another world when you see my signature, and had I not three years ago, after one of your lecture evenings, been able to speak with you, you would probably have to search even deeper down in your memory: Who is this? […] Yes, dear Dr. Steiner, I write to you with a big plea for help at a time of real material need. This may surprise you as you used to know us in more prosperous circumstances.”5

She went on to describe how her family fell on hard times following the death of her husband in 1913 and asked Rudolf Steiner for a loan of 2000 Marks so that she could rent a flat for herself and two of her four daughters. „May I remind you, dear Dr. Steiner, of our longstanding friendship? Of the merry and solemn times we used to spend together? Surely, that will not be necessary, for I am certain that you will help us if you can, for the sake of the children whom you rocked on your knees! […] Our paths have diverged widely. You have become a famous man! I know many—and not the worst—in whose life you have become most important. I also followed your path a little. What you once seemed to appreciate about me when I was ‘the young thing’, as Rudolf Schmidt called me, I still have: a yearning for what lies beyond ordinary life, the interest in something more subtle, more spiritual. I have therefore always liked reading your work and about you. […] And while your path took you somewhere very different from what I expected then, and because you have given me much that stayed with me all my life, I can see from many, many things that you have remained faithful to yourself.”

Rudolf Steiner did help the family. He received the second eldest daughter Eva at Motzstrasse in Berlin and gave her the money, as is apparent from Mila Bock’s thank-you letter of March 5, 1917: „Today I would like to thank you for your generous gift! When I wrote to you it was not my intention to ask for a gift but rather for the loan of a larger sum that I hoped to pay back once our business was running again. But maybe you are right in saying that gift money is better than loan money and I therefore happily accept this gift with as free a heart as the one that gave it. […] Dear Dr. Steiner, it was such a joy that my little Eva was able to meet you, for I have spoken of you and of what I owe you so often over the years that you have become a kind of mystical person for my children; and when they began to attend your lectures and even read your writings, they never tired of asking me about you again and again, even after smallest details, and your Philosophy of Freedom I have to lock away because all my young people are so keen to take it from me. And now you have been so kind, so good to Eva. She writes that it was so wonderful when you gave her the money that she felt she would have liked to embrace you.”

It was a special, freedom-endowing act of Rudolf Steiner’s to give the money not as a loan but as a gift—and Mila Bock felt this deeply. His gesture suggests that he still felt an intimate connection with the family. However, there are no documents that reveal whether the connection lasted or whether any of Mila and Otto’s four daughters had a deeper interest in anthroposophy.

Translation Margot M. Saar

Footnotes

- Letter of May 7, 1894, Rudolf Steiner, Sämtliche Briefe 2, Dornach 2023, p. 565f.

- Autobiography. Chapters in the Course of my Life: 1861-1907, CW 28, Great Barrington 2006, p. 140, tr. Rita Stebbing.

- Probably a reference to the youngest Bock daughter, Hilde Else, who was three years old at the time.

- May 14, 1899. Facsimile in: Rudolf Steiner, Eine Bildbiografie, edited by D. M. Hoffmann, A. Vinzenz, N. Badenberg, St. Widmer, Basel 2021, p. 131. German original: «Wir sind in Milas und Ottos Haus / Niemals schmeisset man uns aus ihm hinaus. / Schliesslich find ich nimmer heim / Solchen schönen netten Leim / Sagt das gute Elsilein / Das ist wieder mal ein Keim / Zum einem künftigen Stell’ Dich / Ein Solches sei euch zur Bowle gesagt / Auf dass kein Groll Euch plagt. / Kein beträchtlicher Dichter hat das gedicht / Aber ein oller ehrlicher Anarchist: / Steiner Anna Eunike Minni Eunike.»

- Rudolf Steiner Archives.