Beauty will save the world! This is what the fool promises in Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s novel The Idiot, and fools tell the truth, the truth that no one dares to tell because it is so simple. But how can this saviour of the world – beauty – be understood?

I was walking with a friend along the Birs, a small river at the bend of the Rhine, engrossed in conversation. It was midday, and the southerly sun was sparkling on the stream. Often I looked past my companion’s mop of hair, similarly lit up, at the glittering, streaming water. Everything glowed with light and peace; it was enchantingly beautiful, idyllic.

A contrasting image from my youth: Year 12. An excursion to Berlin takes us to the eastern part of the city, the then capital of East Germany. When we cross the border, narrow corridors guide us to face the eyes of the border guards behind a glass pane. I will never forget the empty look, the soulless language of the customs officer. In an ill-fitting uniform, he looked at the passport, then at me, then back at the passport and back at me, as if he had practised looking nasty, or was practising punishing me and my image in the passport. A stamp slams down and without a word he waves me away.

Beauty and evil are opposites. This is puzzling because evil is all too happy to seize the beautiful. When that happens, we have something beautiful in front of us and only notice at the second or third glance that something actually far from beautiful is lurking in it or behind it. This is the contradiction that sets the tone at the beginning here.

I followed two pieces of advice on this path to an understanding of beauty. One comes from Joachim Daniel: If you have a question before you that is greater than your ability to find an answer, spiral around it as you approach its centre, encircle and close in on the question, so you don’t rebound off it, and yet don’t lose sight of it. The second piece of advice was given by Ernst Wilhelm Barkhoff, the pioneer of Anthroposophical Banking. He said to a group of young people: If you don’t understand something and you nevertheless want to grasp it, agree to a date to give a lecture on the subject. When Weleda formulated beauty and health as equally important corporate goals, I offered to contribute something on the understanding of beauty. This developed into workshop lectures at the in-house training on the topic of ‹beauty› and can now be read here. I want to approach beauty from seven angles.

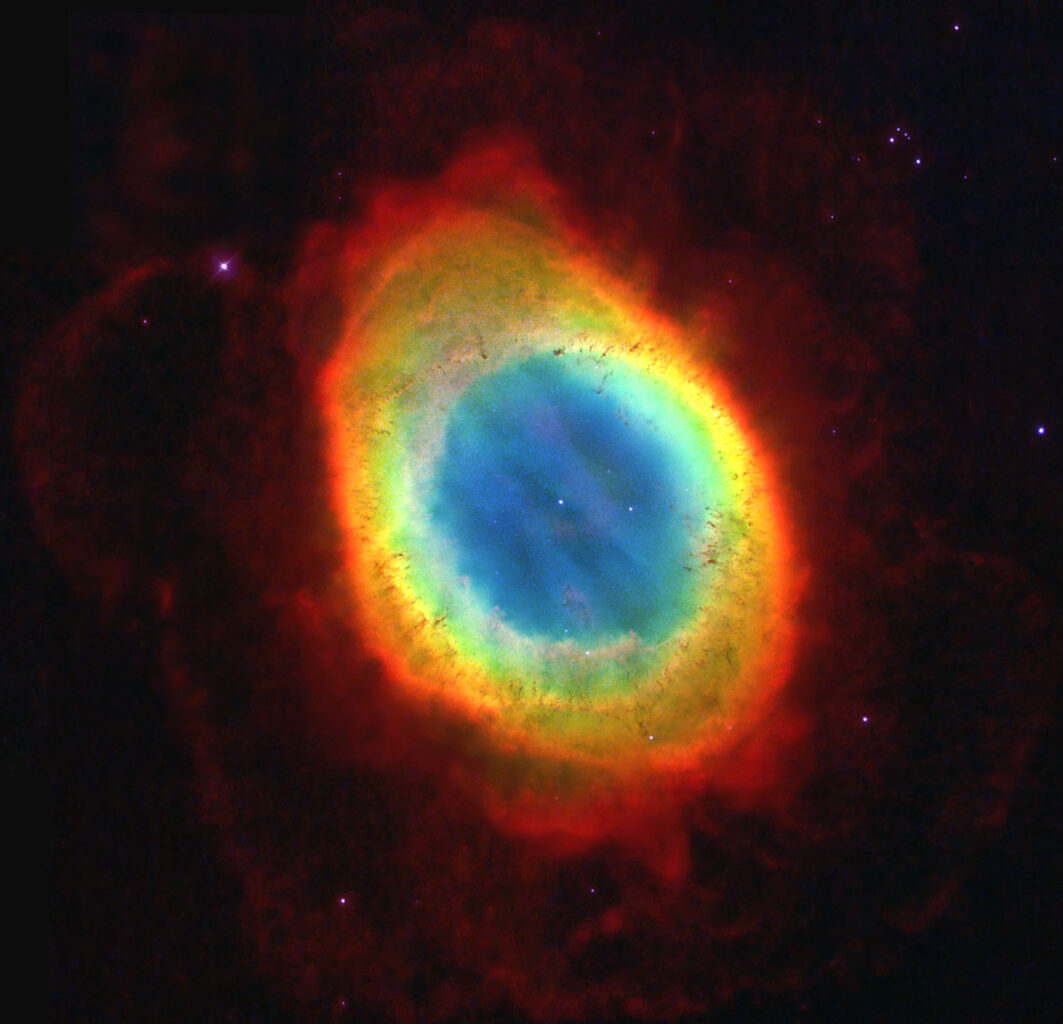

Beauty is Unnecessary

It begins with the philosophical workshop of François Cheng. The Chinese-French philosopher wrote five meditations on beauty.1 In the first, he asks whether it is possible to imagine a creation in which one of the three Christian virtues does not exist. What would a world be like if it did not contain goodness, beauty or truth? I would not have written this text if I could not count on it being received favourably. Without the goodness of our parents, our teachers, we would not exist. A world without goodness, a cosmos without love is inconceivable. It doesn’t take much to understand that. It is similar with the truth. A cosmos in which nothing is true, nothing has validity, but everything is deception, fake news, makes it impossible to live. Nothing could be relied on, there would be no firm ground. An author would not be an author and a reader would not be a reader. Thus Cheng notes: There is no nature, no life, no earth, no existence without goodness, without truth. But existence without beauty is conceivable! A completely ugly world can be imagined, and there are enough stories that picture complete ugliness. Some parts of Eastern Europe, travelers report, had come close to such a scenario of complete desolation during the Cold War, and images of bombed-out Mariopul also come close. This distinguishes beauty from truth and goodness – that creation would be possible without the beautiful. «The universe is not dependent on beauty,» Cheng concludes. And yet the universe is infinitely beautiful, from a meadow filled with flowers, a child’s laughter, to summer rain. That is the greatness of beauty, that it is, though it need not be. It is a gift that comes so naturally to us that we cannot even conceive of a world without beauty. Because the world is beautiful without having to be beautiful, it must want to be beautiful, this world must have freely decided to be beautiful!

Beauty is Unique and Eternal

Back to the Birs: the way the light fell on the water, making the waves glisten and hikers and walkers squint – it will never be like this again. A moment that passes and never comes back. Beauty is one-off. That is the tragedy that belongs to beauty: its does not return! This is how beauty sanctifies the moment. Anyone who has ploughed poppies knows the pain. How quickly the beauty goes. And yet: as unique as this play of water and sun was, such a sight will be seen again. There will be a new, perhaps even more moving, certainly different kind of beauty. That is the promise of beauty, that for all the uniqueness of the event there is and must be a next time. The beautiful moment gives way to a subsequent beautiful moment. Each blossom fades and as it withers promises that there will be further blossoms, further flowering. It would be quite nonsensical if there were only this one beautiful moment, if that was it and no more were to follow. Then it would be meaningless and lost. Thus the beautiful is one-off – which Schiller frames in the words: «Even the beautiful must die. The gods weep that beauty passes away» – and it is eternal. In beauty lies the moment and eternity.

Beauty is Resonant and Urgent

Because the unique instance of beauty is followed by another unique instance, there is much more to beauty than its own return; it is the promise that our personal unique existence has followed another one. Beauty promises immortality in a way that could not be simpler. Now the philosopher Byung-Chul Han writes that we would rarely say that something «is» beautiful, but rather, «That was beautiful!» To capture the beautiful, we must pause to grasp the «fluorescent resonance» of the beautiful. We experience the moment of beauty, he observes, in its echo in the soul. The beautiful sanctifies the moment, but is not exhausted in the now, is not trapped in it, but only blossoms in reflection, in the rumination of the soul. Beauty therefore has its temporality in such resonance. That is why the rapid passage of time does not go well with the experience of the beautiful.

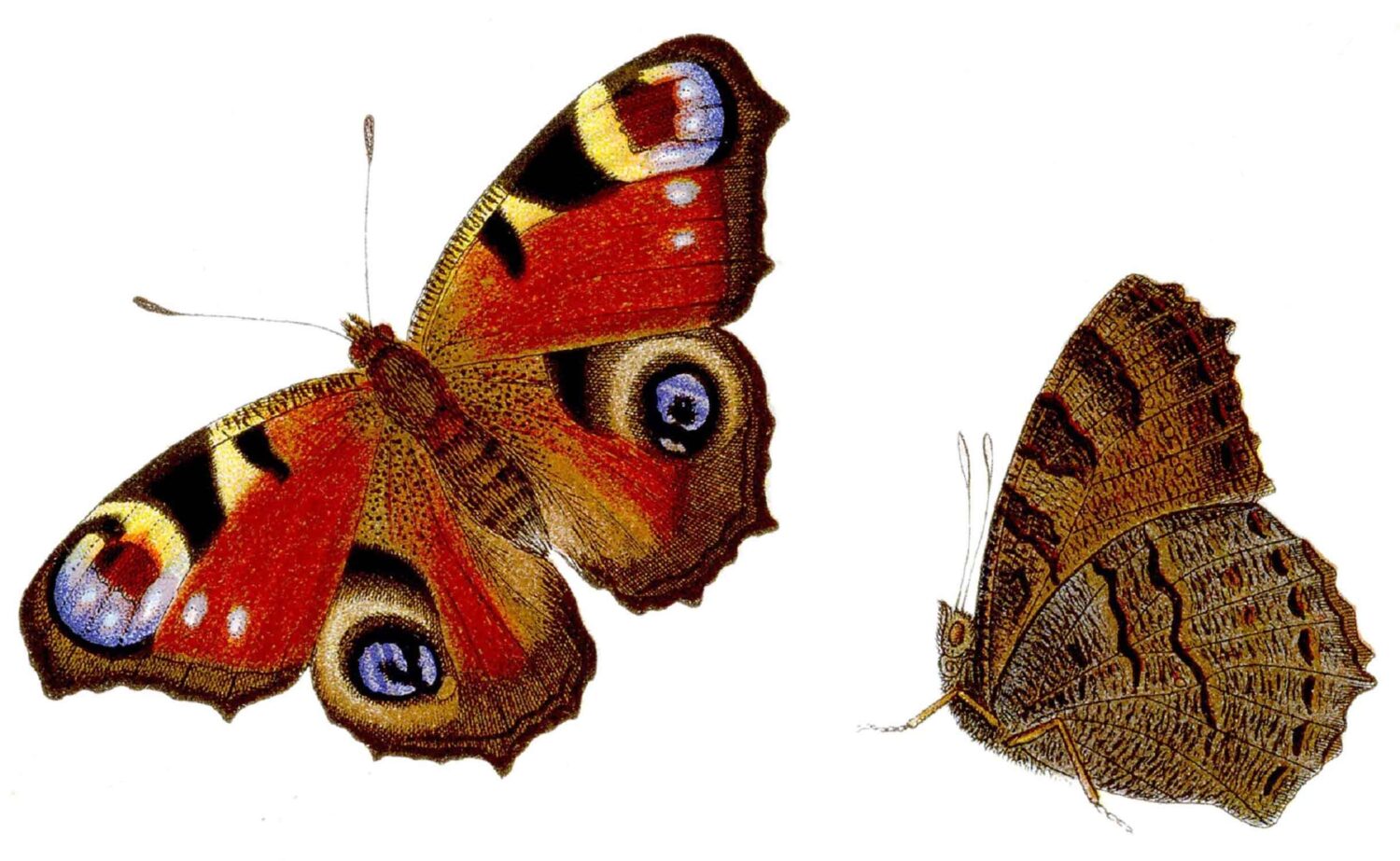

Now, as an echo of the soul, the beautiful not only projects into the future; interestingly, it also has its antecedents, its roots in the past. Every rosebud tells this story! Now we are getting closer to the core of beauty. The rose is beautiful. At the same time, we sense in beauty the will to be beautiful, to become beautiful. That surrounds the bud like an aura: «I will blossom!» That is the drive towards beauty. What a contradiction: the beautiful knows no intent and yet is pressing towards beauty! A secret will can be felt and we humans share this will with all of creation: We want to be self-confident, we want to appear smart, but deep in our souls we want this above all: to be beautiful! François Cheng puts it this way: We want to be in touch with the splendour and glory of the universe. When the drive to be beautiful lives in the beautiful, then beauty is not just an image, it is a force! An illustration:

A few years ago, I attended a reading by the German-Turkish journalist Deniz Yücel. He told of his imprisonment, largely in solitary confinement. The Turkish prison, he said, had been a symphony of metal and stench and steel. At the end, a microphone circulated, I took it and asked how he had survived solitary confinement. He was about to answer in his usual political way, but then reconsidered: «I’ll tell you something different. I took a yoghurt pot and hid it. I made a substrate out of crushed eggshells and the contents of tea bags. We were given seasoning for the food, so I took a tiny mint plant and planted it in my artificial soil and hid it from the guards in the fridge.» This mint plant, which drooped so crookedly at first and then straightened up, the beauty of this little plant, he said, had saved him. In the symphony of reinforced concrete and stench, this mint, the beauty of something coming into being, stood by him. More than the mint and its beauty, it was this power, this hymn of beauty that saved him.

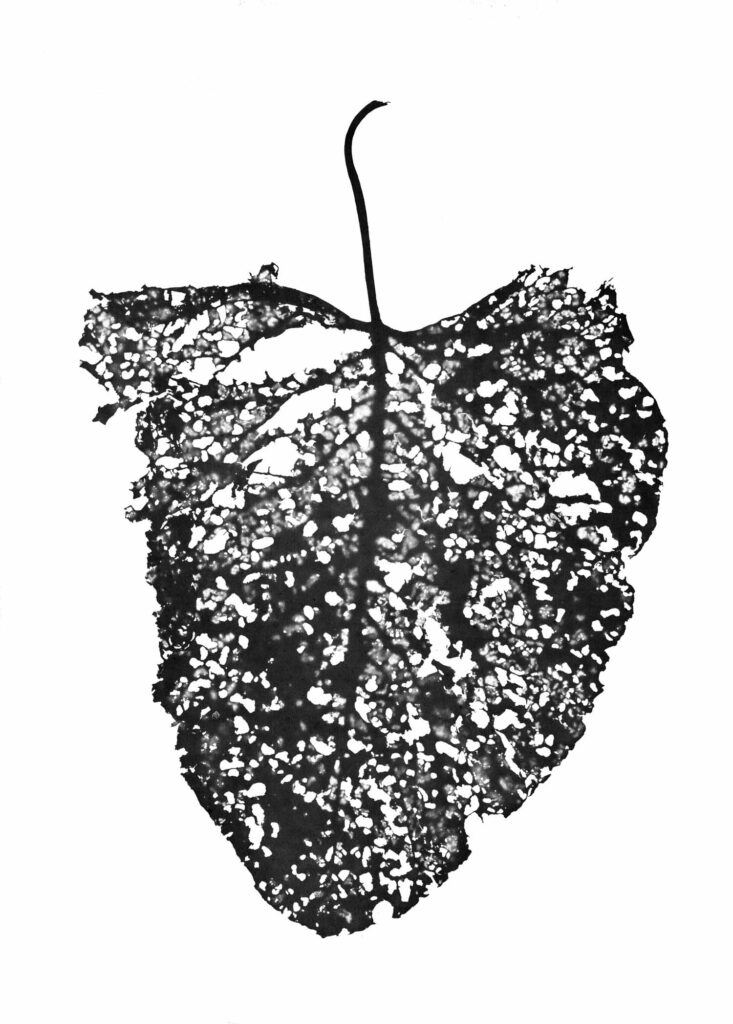

Beauty is Concealed

«Nature loves to conceal herself» writes Heraclitus.2 Indeed, beauty often conceals or camouflages itself, it cannot be grasped at first glance. I learned to understand this in a seminar with the artist Alexander Schaumann. Perhaps 15 years ago, he started offering seminars in observing the human being.3 You sit in a circle and look together at a person, their figure or perhaps just their eyes. We had a Korean Eurythmy student in front of us. Together we characterised what we saw and with each opinion the attentiveness in the room increased, the organs of looking, empathy and understanding growing in the group. From minute to minute our ability to observe increased and the student became more and more beautiful. I understood the real magic of this class when I sat next to the Eurythmist at the meal afterwards: her grace, the visibly invisible currents around her body, the light around her eyes and forehead, in short her unique beauty had faded away. Were we deceived? It was as if she were a different person. So there is a beauty that depends on increased attentiveness.

I suspect this is especially true of the human face. That is where this mystery is strongest, where the unique is so commonplace. Perhaps this is the «romanticising» that Novalis speaks of when he calls out to us: «The world must be romanticised. That is how the original sense can be found again.» More on the word sense later. He goes on to write: «By giving the commonplace a lofty meaning, the ordinary a mysterious glance, the known the dignity of the unknown, the finite an infinite semblance, I romanticise.» To give the dignity of the unknown to the known is to look with new eyes, with a question, at everyone and everything. And in his Fragments he writes that the painter should «see the world as beautiful», complete it, perfect it. That is the human ability, that we can bring beauty to light past the blemish. That we can see something as beautiful, see it in greater perfection.

The sociologist Georg Simmel says about the human face that it is part of the modern age, that we see many people but do not hear them speak. We see a hundred faces on the street, but we do not hear the voices that belong to them. Sometimes I sit opposite someone on the train and think: «What an interesting face, but I don’t understand it!» Simmel says that is almost always because a face is so rich, because the whole biography is contained in it, that we don’t understand it. As soon as the person begins to speak, it becomes understandable. That’s why I ask: «What’s the next stop?» in order to hear the face, in order to understand the face.

Beauty Makes Things Beautiful

That the sight of beauty transforms the beholder is something I experienced at the other end of the world. A solar eclipse took me with twelve interested people to Easter Island in the South Pacific. A married couple from Munich, Franz and Elisabeth Wiegand, who had saved up for a long time for this expensive trip, were also there. In the loneliest place on earth, surrounded by the silent stone figures, the Moais, the moon covered the sun and made the mysterious halo of rays visible in front of the anthracite-coloured moon, I glanced over at her, at Elisabeth Wiegand.

She was looking up with an open, still gaze. The profound emotion and reverence in her moist eyes enchanted her features and her whole figure. I could not decide which was more beautiful, the spectacle in the heavens up there, which we had travelled over 12,000 miles to see, or the face of Elisabeth Wiegand. We become more beautiful at the sight of beauty. The beautiful inspires. Beauty makes us beautiful. That is why Waldorf schools are beautiful, because they let the pupils become more beautiful. The former Widar Hospital in Järna: such wide wooden corridors, what a beautiful hospital! Yes, beauty is contagious, a pandemic. Therefore anyone who takes their time in front of the mirror as they dress does much more than make themselves look good, they make all those who see them, their surroundings, more beautiful.

Beauty is Good

It can also happen that appearances are deceptive, that beauty is deceptive. This was mentioned at the beginning. Because beauty is so attractive, because the longing for it is great, it is an obvious thing to seek to make a profit with beauty. It becomes an artifice. Its pressing and resonant nature, beautifying the viewer – that is absent here. How do we recognise the deception? How do we recognise the difference between what is an artifice and what is real, original beauty? The French philosopher Henri Bergson provides a key to this: «Thus the person who looks at the universe with the eye of the artist will experience the grace of the universe through beauty and see goodness shining through grace again.»4 Bergson calls it a triad. First you have to look at beauty with the eyes of an artist. It is up to these eyes to examine whether it is an artifice, is pleasing, or is truly beautiful. Under such eyes, Bergson says, grace is revealed in the beautiful, that is, humility, naturalness and comeliness. And secure and hidden in within it, goodness and love now glimmer. Beauty becomes grace and grace becomes goodness. When I look at beauty, do I feel that grace speaks in it and goodness resides there?

Beauty is Without Intent

«The rose has no ‹why›/ It blossoms because it blossoms / It pays no attention to itself / It does not ask to be seen», writes Angelus Silesius. Indeed, intent deprives beauty of its grace and yet it nevertheless is pressing to appear. It guides us, as François Cheng writes, into the «dawn of the universe.» If beauty «guides us», then it has a direction. This directs the gaze towards the word «sense», which in English as in German has three levels: You can look at beauty, it is sensory. It has meaning and therefore a «sense», it is therefore sensory and has a sense. And finally, it contains a direction, a meaning that leads beyond our own person.5

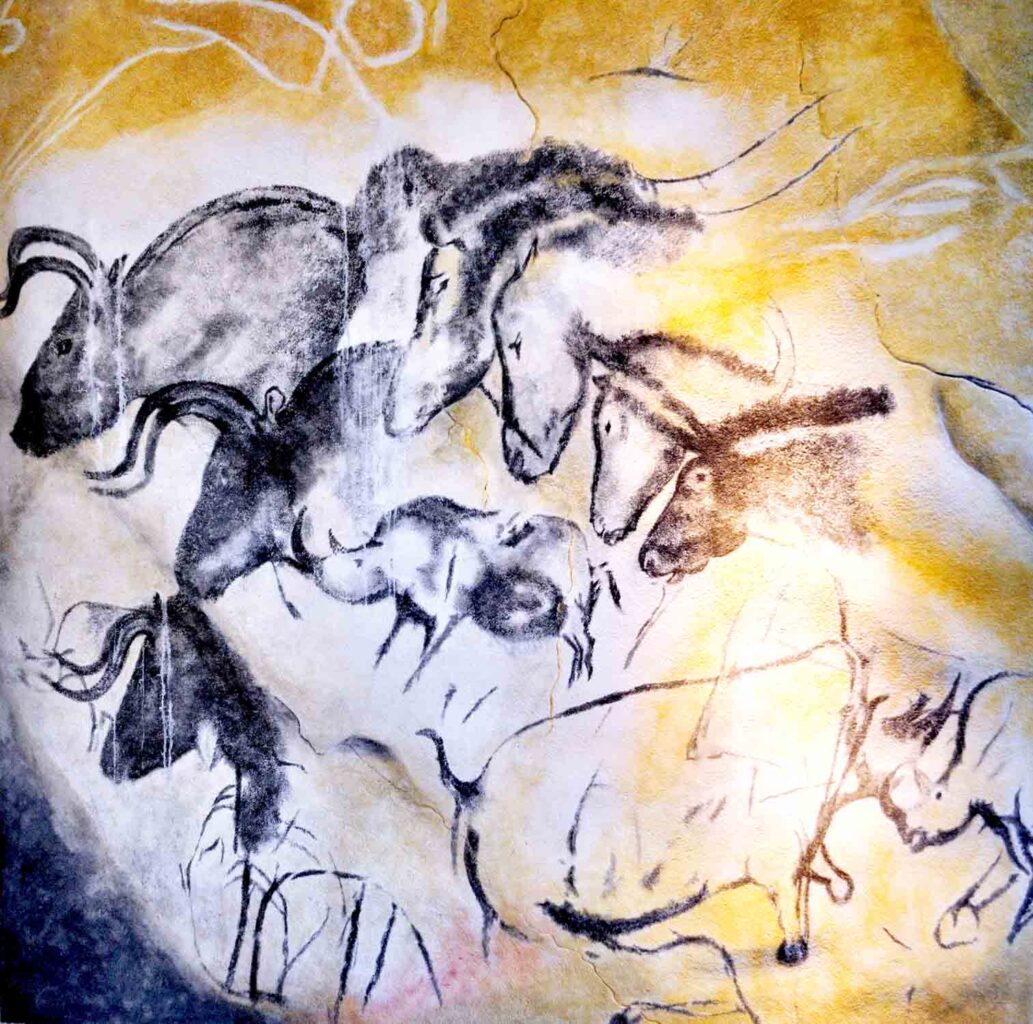

Beauty is Divine

Probably no one who talks about beauty can avoid Plato. As is so often the case, the most important thing is said at the beginning also as regards the question of beauty. In Plato’s Symposium, Diotima, the blind seer, talks about beauty. It is the only time that Plato places a woman at the centre of the conversation and, as in all Platonic dialogues, the entry into the subject is also its foundation. To Diotima’s first words, Socrates replies that he would have to be clairvoyant to understand her exposition. Even Socrates, the cleverest of them all, is overwhelmed and cannot follow her. Then Diotima continues: «I will tell you more clearly, then. For all humans, O Socrates, are fertile both in body and soul, she said, and when they have reached a certain age, their nature strives to procreate.» From a certain age, it is part of the human being to bring forth spiritual things. Martin Buber calls it the urge to create in human beings, the longing to produce something.6 «But it cannot produce in the ugly, but only in the beautiful.» In fact, in a climate of resentment, anger or hatred, no one will be able to create anything. The soul grows beyond itself, it is able to create and give birth when it connects. And it connects with the higher, the beautiful, not with the ugly. The ugly leads it back to itself.

Diotima says similarly: «Beauty, then, is a Goddess that acts like an initiator or midwife for creation. For love, O Socrates, is not concerned with the beautiful, as you think. – With what, then? – With creation and birth in the beautiful.» We do not love the beautiful, but what arises at the sight of the beautiful, the will and longing to bring forth ourselves what is beautiful, what is eternal. Thus we have a triad that occurs through the beautiful: The beautiful allows its beauty to unfold in the beholder, it awakens love and goodness in him or her, because the good is hidden in the beautiful, and it drives him or her to also bring forth the beautiful. And because this beauty has a share in the eternal, it connects the soul with the eternal, the immortal.

We Humans Become Divine

If you want to inspire your counterpart in conversation, you will take up their images, feelings and ideas, indeed making them the raw material of what you have to offer. Something new thus grows out of the spiritual life of the other which we are able to perceive. It is no different when angels and higher beings inspire us humans, when they create something new with and from us. Then they extend our feelings and thoughts. The oft-quoted phrase: «Today’s thoughts are tomorrow’s reality» has its spiritual dimension. Wim Wenders captures it in the film Wings of Desire.7 A camera moves through a library, a vast landscape of books, and the whispering of a multitude of voices lets us hear the thoughts of all the readers who enter into the picture. Angels bend over many of those thus immersed and take part unseen, indeed they immerse themselves in the spirit that all the students awaken from the books to new life. Some children working on their school reports in the book world nod at the angels as if they were familiar with each other. The scene reveals that we are reading and thinking «for» the angels.

It is part of the esoteric training in Anthroposophy that the future is formed out of this community, that the gods carry this supersensory element obtained in human thinking back into the sensory world. Human ideas and feelings become the raw material of a new world. Where we experience the beautiful, we ourselves perform this divine service, it is we ourselves who – as Plato describes it – give birth and create in the sight of the beautiful. Where we experience beauty, we ourselves become more beautiful, it awakens love in us, and inspires us, we thus build a new world. In the sight of the beautiful, the god, the goddess in us emerges, enters into the deed, and it is we who save the world.

This article was translated by Christian von Arnim.

Footnotes

- François Cheng, The Way of Beauty. Five Meditations for Spiritual Transformation. Rochester 2009.

- Heraclitus, Fragments. B 123.

- Wolfgang Held, Goetheanum No. xxx 2014 ‹Menschenbetrachtung›.

- Henri Bergson, ‹Denken und schöpferisches Werden›. Frankfurt 1985, p. 270

- This meaning of the word ‹sense› as having a direction is nowadays only familiar to us any longer from “sense of rotation”.

- Martin Buber, Reden über Erziehung. Gütersloh 1953, p. 15.

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3LsUFzuTeS4

Best wishes,

Giuseppe

Most interesting! The other night I filled the blank space but disappeare suddenly…..