Not everything is loud, shrill, and terrible in the world today. There are also quiet tones that are easily overheard, especially amidst the media hype. When they come along directly, with nothing else intervening, they are a source of strength. This is about an unexpectedly beautiful encounter.

There was almost a Whitsun mood on that Friday evening in Weimar, in the square in front of the palace. Little and big people on the grass eating evening picnics and a ping-pong table in front of the cube that houses rotating exhibitions in the warm season. Deckchairs had even been set up by the Classicism Foundation and a DJ played music suitable for general dancing, to which some were already moving. Just then, a man with a vendor’s tray came strolling through the crowd. You don’t tend to see that very often these days. He wore a kind of Bavarian hat, his clothes casual, his gaze open, not shy, not intrusive. He meandered in this way in our direction, wanting to show us something he was carrying in the tray. They were little books, fat and in a peculiarly long landscape format. At the front of the vendor’s tray hung an invitation to visit his ‘travelling exhibition’. So that’s what he was carrying around with him!

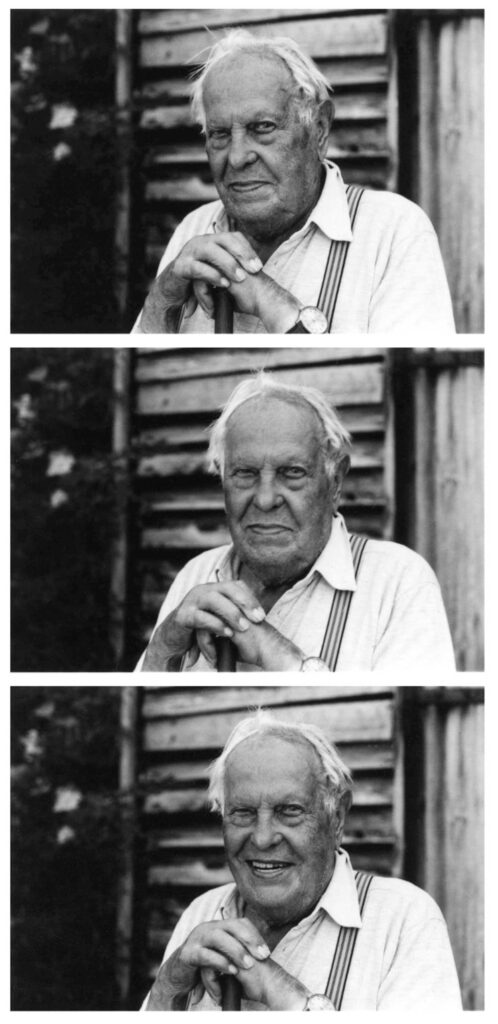

He presented the flipbooks—his works—and asked if we wanted to see any. Of course! The first was created twenty years ago and showed the moment when a young girl opens her eyes in front of the mirror after having asked to have her long hair shaved off with her eyes closed. Volker Gerling, the ‘flipbook cinematographer’, had captured this moment. It was done lovingly and beautifully. He then told us how and where he had met this young girl called Antonia and that he would now visit her again on this trip. He knew the stories of the people in all his flipbooks and the circumstances in which they were taken. Volker’s analogue camera takes as many pictures in twelve seconds as he needs for a flipbook. For the small movie of a men’s toilet room in Berlin, he’d had to do quite a lot of explaining during the recording. Little blackish-grey men move like ants while we flipped through the pages in an elongated landscape format.

One of his works shows a man’s gaze slowly wandering towards the mountain face opposite, which of course cannot be seen, as he questions himself about death. The moon is also moving across the scene above the Berlin Cathedral. The bashful yet joyful smile of the woman in the mountain stream, who finally dared to bathe there after ten years, is wonderful. Then there is the ‘ménage à trois’, where a woman turns her head to her two lovers on her right and left. Volker is still in contact with these people, too.

He showed us each of his flipbooks three times. The first view is to enter, the second view to enjoy, and the third view to take leave again. He then asked if we want to donate something for his exhibition which would finance his travels. The donation box was attached under the vendor’s tray. He had left his home in Templin, north of Berlin, three weeks before and was ultimately heading to Austria via Freiburg and Basel. There are some fixed stations where he can stop off, but usually, he sleeps in the forest, which he likes very much. A small trailer, which he pulls behind him on a harness, transports a tent, food, and photo equipment. It was clear from his eyes that he was looking forward to the unpredictability of his journey and new ‘material’. In this way, I would say, he turns documentation into an art.

Actually, Volker studied directing and cinematography. Traveling by train was the precursor of film, his professor said at one point. And for Volker, rambling, walking, is the most fitting counterpart to the flipbook. Then we talked about slowness, which we seem to have lost today. I would love to be a fly on the wall for the conversations he will continue to have on his journey.

Rarely have I seen such restrained beauty, so unexpectedly. It was a little bit like magic. Volker Gerling’s works—and his manner, too—were so wonderfully unpretentious, a good combination of freedom and love. He does what he loves and at the same time makes others appear as they are, in an artistic way, engaged in life. There is something gentle about it, facing one’s own existence and the world. It is harmonious. His wanderings, his way of meeting people and processing these encounters in such a way that new encounters arise from them—it is almost like a perpetual motion machine. And if other people are as enthusiastic as we were, then Volker Gerling will generate good forces from small moments of looking at pictures. He appeared to me as profoundly himself, a human being—someone you meet in the street, not in the hubbub of the financially powerful art market, like Hermann Hesse’s Goldmund. That, then, also exists in the world today—fortunately.

Translation Christian von Arnim

Image source and more Daumenkinographie