The book ‹Bridge Over the River› is well known in Anthroposophical circles. It contains the communications of the late Sigwart of Eulenburg from the afterlife. It’s less well known that he was indeed an important composer during his lifetime. Johannes Greiner, a co-worker in the Section for the Performing Arts, set out to investigate.

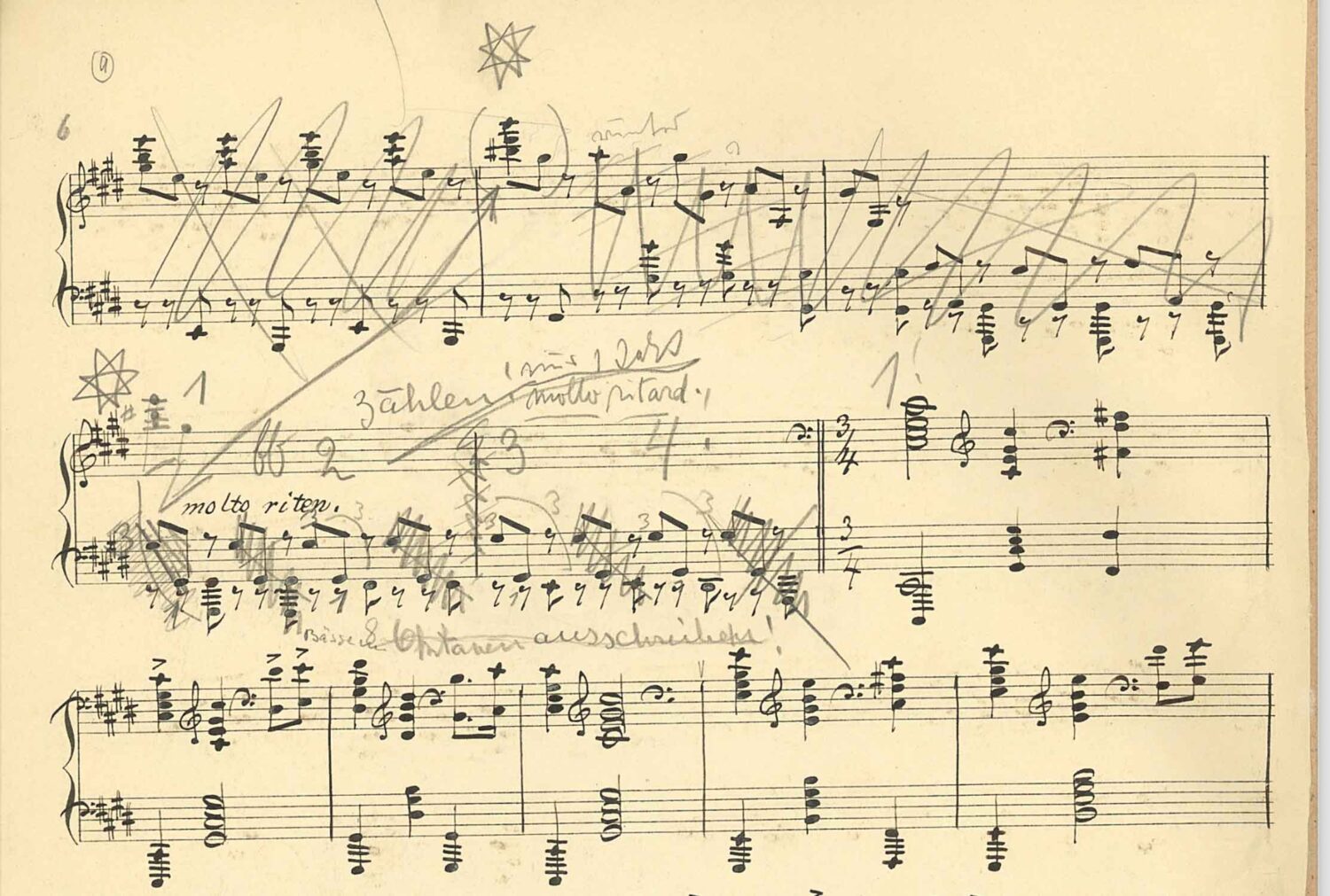

On May 9th, 1915, Sigwart, the Count of Eulenburg, was wounded by a bullet in his lungs during the assault by German troops on the Russian fortifications of Leki at the heights of Gorlice in Galicia. He then spent three weeks in the military hospital in Jaslo (Poland), where he died on June 2nd, 1915 before dawn, at about 3.30 am. He had with him the Piano Sonata in D Major op. 19, freshly composed in the trenches.

Botho Sigwart, as he called himself as an artist, was very close to his two sisters: to ‹Lycki› (Augusta Alexandrine Countess zu Eulenburg-Hertefeld, 1882-1974), who was one year older and liked to paint, and to ‹Tora› (Viktoria Ada Astrid Agnes Countess zu Eulenburg-Hertefeld, 1886-1967), who was one and a half years younger and played the piano well. Sigwart was also very close to his sister-in-law Marie Fürstin zu Eulenburg-Hertefeld (1884-1960), who was married to Sigwart’s brother ‹Büdi› (Friedrich Wend Fürst zu Eulenburg-Hertefeld and Graf von Sandels, 1881-1963). She witnessed his death from afar. A few hours before his death, he appeared to her in a state between sleeping and waking and gave her the understanding that he would now need a lot of strength. At the moment of his death, she was jolted out of sleep: «After a while, I fell asleep again, but was roused after two hours of deepest sleep. It was half past three o’clock, the first dawn was flashing through the store cracks. Quickly I opened the window. The cattle in the stables were bellowing in fear, high in the sky was the crescent moon, it rumbled eerily over the whole country. Then I realized that an earthquake had struck the area. Then the memory of the night’s experiences came back. Later I found out that the second awakening by the earthquake coincided with the moment of Sigwart’s liberation from his body. That was June 2, 1915.»1 A few days after his death, Marie Fürstin zu Eulenburg-Hertefeld dreamed of Sigwart: «He was standing in the castle where I had spent my childhood, at the top of the great flight of steps leading down into the hall. A white, flowing robe enveloped him. He called down to me in the hall: ‹Marie, have you still not prepared a place for me to lay?›»2

Other Dreams Followed

During this time, Sigwart’s sister Lycki was often with Marie. She too felt that her brother was hoping for something from her. She became restless and even tried to see if her brother would perhaps guide her hand from the other world if she surrendered her will completely to him while writing. But this did not happen. After an operation in Munich, as a result of which Lycki had to lie still for a while, she returned to Marie very changed and much calmer and more relaxed. The latter reports: «Lycki brought us a document and said: ‹In the seclusion and silence of these days I have understood what Sigwart expects of me. It is not my hand that he wants to influence by pushing from outside, I myself must open a door in my brain, then I will hear his words, which I am to write down.›»

Lycki wrote down the first communication from her deceased brother on July 28th, 1915 – 56 days after his death. Over time, the messages became more nuanced, substantial, and multi-faceted. After a few weeks, his sister-in-law Marie was also able to receive messages from the deceased, and later his sister Tora. When Sigwart’s cousin Dagmar von Pannwitz, née Countess of Dankelmann, died on 9 June 1935, it was not long before she, too, was able to send her messages from the hereafter through Sigwart’s sisters and Marie Princess of Eulenburg-Hertefeld, who had been a friend of hers in life. Thus, over the decades, a rich exchange unfolded between the world of the deceased and the world of the living. A ‹bridge over the river› was built. Sigwart’s communications from the afterlife span 35 years and comprise 1500 typewritten pages.

At first, those still living doubted the authenticity of Sigwart’s messages. Precisely because of the desire that it should be true, it had to be judged all the more carefully whether the messages really came from the deceased brother or whether it was a matter of illusion or haunting by other beings.

Consulting Anthroposophy

Initially, in September of 1915, the Anthroposophist Ludwig Deinhard (1847–1918) was asked for advice. When he heard about the matter, «he was friendly but dismissive and advised us not to be misled.»3 But when the communications were read to him, he changed his view and no longer doubted Sigwart’s identity regarding these messages. Marie reports: «We were very happy but nevertheless, after a short time, the desire arose to also consult what we considered to be the greatest authority in the field of spiritual science, Rudolf Steiner. I was entrusted with the mission and so on a dull December afternoon, I went to Motzstraße with our treasures, which had already reached quite a volume, under my arm. Lycki had informed Dr. Steiner in advance by letter what it was all about. Dr. Steiner received me very kindly and asked if he could keep the texts for a while. I should come back in two or three weeks, then he would talk to me about it.

The day4 came and I must confess it was probably one of the most anxious of that period. What would he say? This question was before me in large letters, for by now the edifice of belief in Sigwart’s identity had grown very much in me, strengthened by my many dream experiences with him, through which he had come ever closer to me, much closer than ever during his time on earth. For one and a half hours Dr. Steiner went through page after page of the messages with me, put some things that were not understood into perspective, explained how Sigwart would have meant this or that, and asked me questions. […] In vain I waited for the rejection of some communication, none came! At the end he said at the parting: ‹Yes, these are exceptionally clear, absolutely authentic transmissions from the spiritual worlds. I see no reason to advise you to stop listening to them.› […] Still, at the farewell he emphasized that transmissions of this kind were very rare. I felt that it was genuine joy that he felt, and fellow joy with us.»5 Irmgart Reipert6 discovered that on the day the fatal shot hit Sigwart, Rudolf Steiner spoke about the necessity to build a ‹bridge over the stream›. In the lecture given at the same time in Vienna, published with the title ‹The Dead as Helpers of the Progress of Humanity›, he said:

A connecting bridge is to be built through spiritual science, precisely in the near future, between the living and the dead, a connecting line through which the inspiring elemental forces of those who have made the great sacrifices in our time can find their way across. […] So that our souls may become expectant, expectant of the inspiration which will come from the dead, but which in the spirit will become especially alive.7

For a long time, Sigwart wanted the messages to be kept secret. A small circle of the family knew about them and let themselves be inspired, motivated, comforted, and encouraged in their own meditative practice by the deceased. In December 1915, Rudolf Steiner also spoke out in favour of such secrecy to protect the precious revelations. But the day came on 25 April 1942 when Sigwart suggested that the messages should be published after all, for the comfort of people who had already had to experience two world wars in such a short time. In 1950 – exactly in the middle of the century – the first pamphlet was published, followed by others. In 1985 they were compiled by Herbert Hillringhaus into one volume with an introduction by Fred Poeppig under the title ‹Brücke über den Strom – Mitteilungen aus dem Leben nach dem Tode› (Bridge over the River – Communications from Life After Death), published by Novalis Verlag. The publication found many grateful readers. The book had to be reprinted again and again. In the meantime, it has become an indispensable standard work for all those who occupy themselves with life after death. If someone’s acquaintance or family member dies, this book can be given to their loved ones as a comforting gift. In 2018, a second volume edited by Peter Signer was published with previously unpublished communications from Sigwart. Peter Signer had already published ‹Mitteilungen von Dagmar – aus dem Leben nach dem Tod› in 2016.

Also a Living Person

Thousands of people have read ‹Bridge Over the River› and gained comfort and insight into the soul’s path after death. Thousands know Sigwart as a deceased musician who speaks to the living. Few know him as a composer. The musical works he created in life are largely forgotten. But what he helped to create in life after death became famous. In this, Sigwart is very special. Most of the time, people know the living and lose sight of them when they begin their journey after death. Sigwart became famous years after his death for what he transmitted to the living after death. Now the time has come also to honour him as a living person and to rediscover his musical works.

Sigwart was born in Munich on the 10th of January, 1884, as the sixth child. His father was Philipp Friedrich Alexander Prince of Eulenburg-Hertefeld and Count of Sandels (1847–1921). He became Prussian Prince of Eulenburg und Hertefeld with the title of Serene Highness on 1 January 1900. Sigwart’s mother was Augusta Ulrika Constantia Charlotta Princess of Eulenburg-Hertefeld and Countess of Sandels (1853–1941) who came from Sweden. Sigwart’s mother Augusta’s father was Count Samuel August of Sandels, Swedish Lieutenant General, Governor of Stockholm, Commanding General of the Guards. Her paternal grandfather, Count Johann August of Sandels, was a Swedish field marshal and viceroy of Sweden and was given the extremely rare title of ‹One of the Lords of the Realm›, which was the highest honour in Sweden and brought with it the salutation of ‹mon cousin› by the king. Sigwart thus entered a highly respected family.

His two oldest siblings had died at an early age. After him, the sixth child, another brother, and a sister were born, so he grew up as the fourth oldest of six siblings. In the first week of his life, he contracted measles, which his mother had also contracted in childbirth. He hovered between life and death. What later became his mission – to mediate between the realm of the dead and life and thus bridge the threshold between the worlds – was foreshadowed by the infant hovering between life and death as soon as his first days on earth.

His father’s singing had a special influence on the child. A few months before his death, Sigwart wrote to his wife from the front on January 28, 1915: «Papa’s ballads, sung by himself, were my first very deep musical impressions. In our wonderful childhood, Papa’s music already played a great role for me. I am also very close to him in my musical sensibilities, and the simplicity of his expression is something that I return to myself.»8

Incidentally, apart from various political disappointments and slights in 1881 – three years before Sigwart’s birth – it was above all the death of his diabetic daughter Astrid on March 23rd, 1881, that led the father to abandon political goals and turn increasingly to art. Thus Sigwart was born to a father who – in order to come to terms with his daughter’s death – increasingly wrote poetry, composed, and sang.

Sigwart began composing at the age of seven. He received his first music lessons from 1891 to 1904 in Munich from Count Spork and from 1895 to 1898 from the music teacher Robert Gound in Vienna. He often improvised when Kaiser Wilhelm II visited his father. The Emperor was impressed by the boy’s ability and ordered variations on the Dessau March from the eleven-year-old, which Sigwart joyfully composed and was then allowed to premiere with the orchestra in the great music hall in Vienna, conducting himself. In 1898 Sigwart went to Bunzlau grammar school in Silesia, where he received organ lessons from the town’s cantor Wagner. He was then allowed to play at church services and improvise at communion. A year later he transferred to the Luitpold Gymnasium in Munich and again a year later – after a period of private study – to the humanistic Friedrich Wilhelm Gymnasium in Berlin, where he passed the Abitur (school-leaving examination) at the age of 18. Already a year earlier, he had taken part in the Bayreuth Festival rehearsals in 1901 at the invitation of Cosima Wagner and was often allowed to stand in as conductor. In private, he was regularly taught by his former tutor and friend Hans Mayr, a poet and writer who was well-known in Bavaria at the time. Starting in 1902 he studied history and philosophy in Munich and received his doctorate in 1907 with his thesis ‹Erasmus Widmann’s Life and Works›. (Erasmus Widmann, who was born in 1572 and died in 1634, was a German organist, composer, and poet). At the same time, however, he also studied music with Professor Ludwig Thuille (contrapuntal studies) and Court Music Director Hermann Zumpe (orchestral studies). He lost both teachers to early death. In 1908 he went to Max Reger and completed his studies there in 1909. He practised steadily with the organ and completed his organ studies in 1911 in Strasbourg with Albert Schweitzer. He also dedicated his organ concerto, the Symphony in C major op. 12 for organ and orchestra, to him.

Contact with Rudolf Steiner

In 1902 Rudolf Steiner began to present his spiritual-scientific research within the circles of the Theosophical Society. In 1904 he founded an Esoteric School, whose students received help from him on the path of knowledge in the form of meditations, practice instructions, and individual advice. From 1906 Sigwart belonged to the group of people around Rudolf Steiner who wanted to work more intensively on their own development: «Apart from his music, Sigwart was very interested in everything spiritual, in Buddhism, Theosophy, Anthroposophy. He knew Dr. Steiner personally and belonged to the first more intimate circle around Dr. Steiner from about 1906.»9

This was reported by one of Sigwart’s sisters. In the new edition of ‹Bridge over the River – Communications from Life after Death› (2008) it says: «Through the family’s acquaintance with Dr. Rudolf Steiner, who was an occasional guest at Liebenberg,10 Sigwart became acquainted with Anthroposophy, which from then on became more and more the focus of his life. Besides studying the basic works, he took every opportunity to listen to Steiner’s lectures. He shared this interest with his siblings Lycki, Tora and Karl as well as his sister-in-law Marie. Thus the basis had been laid for communication after his step into the spiritual world.»11

In 1909 Sigwart married the concert singer Helene Staegemann, whom he had met while studying with Max Reger in Leipzig.12 She was highly esteemed as a singer – among others, Carl Reinecke and Hans Pfitzner dedicated songs to her. His son Friedrich Max Philipp Donatus (Friedel), born in 1914, who also became a composer and music director and was later given the additional name Sigwart at his mother’s request, died early of meningitis in 1936 – only 22 years old – during a military exercise.

Sigwart had a broad educational horizon and found it a matter, of course, to continually expand it. He also enjoyed traveling. In particular, his horizons were broadened by a long-planned, longed-for study trip to Greece with his wife Helene, which finally took place in 1911 and left a lasting impression on him. They were deeply impressed by Athens, Delphi, and Cape Sounion. At the Bay of Eleusis, they came across the house of Euripides near Salamis. This journey resonated in three important compositions. As op. 15, he composed the melodrama ‹Hektors Bestattung› (Hector’s Burial) based on the 24th canto from Homer’s ‹Iliad› in the translation by J. H. Voss, which is available in a version with orchestra and one with piano accompaniment. Wilhelm Furtwängler, a friend of Sigwart’s, conducted this work at its premiere in the Berlin Philharmonie. When it was performed at the Gewandhaus in Leipzig, the conductor Arthur Nikisch subsequently ordered a symphony from Sigwart. Another Greek-inspired melodrama appeared as op. 18: the ‹Ode der Sappho› (Ode of Sappho) with accompanying music for piano. In 1912 and 1913 Sigwart composed the opera ‹Die Lieder des Euripides. Eine Mär aus Alt-Hellas nach Texten von Ernst von Wildenbruch› (The Songs of Euripides. A Tale from Old Hellas based on Texts by Ernst von Wildenbruch). Unfortunately, he was not able to experience its performance. At first, the premiere was postponed for a few weeks because Sigwart’s wife was still too weak to attend a performance after the birth of their son, then the war broke out. It was only after his death that it was performed with great success by Max von Schillings at the Königliches Hoftheater Stuttgart on December 19th, 1915.

Sigwart was of delicate health and because of his weak lungs he was not in the military. When the First World War broke out six months after the birth of his son, he immediately volunteered. He was 30 years old. After training in a cavalry regiment, he was posted to the west (Flanders and France), did not see action, but was able to work on his second piano sonata in the winter of 1914/15. Thanks to his family’s good connections, he managed to have himself transferred to the Eastern front after six months, where he was finally able to take part in the fighting. He completed the Second Piano Sonata in D major op. 19 in the trenches, dedicating it to his cousin Dagmar. No sooner had the work been completed than he was shot in his already weak lung, which led to his death.

Later he ‹spoke› about how he already felt death coming at the time of the First World War and how he was aware that Sonata op. 19 would be his farewell work: «I knew very well at that time that this music was my swan song, and that is why I was granted to feel, to taste and to experience the highest thing that a human being is capable of during his lifetime, namely absolute detachment and reaching into high worlds. Believe me, I too was in tears when I had to create the Adagio. The immediate experience of my parting from this world, so sunny to me, was a pain that made my heart tremble. I almost wanted to flee, to get out of the slowly developing lament. It held me with an iron grip, and a higher command forced me to persevere in order to complete this last work created with my lifeblood.»

At the beginning of this year, the Sonata op. 19 appeared in print for the first time (Edition Widar, Hamburg) and is now accessible to a wider circle of interest.

Translation Christian von Arnim

Footnotes

- Peter Signer ‹Mitteilungen von Sigwart aus dem Leben nach dem Tod›,Norderstedt 2018, p. 13.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., p. 17.

- It was December 6, 1915.

- Peter Signer, ‹Mitteilungen von Sigwart aus dem Leben nach dem Tod,› Norderstedt 2018, pp. 17 ff.

- Peter Signer, ‹Mitteilungen von Sigwart aus dem Leben nach dem Tod›, Norderstedt 2018., p. 477.

- Rudolf Steiner, The Mystery of Death. GA 159/169, Dornach 1980, p. 202.

- Prince Philipp of Eulenburg, Eine Erinnerung. No place or date, p. 4. (First printed as a manuscript, Liebenberg 1918.)

- Brücke über den Strom, Volume 1, p. 10.

- The family’s castle in Brandenburg, north of Berlin.

- Brücke über den Strom, Volume 1, p. 11.

- He described on February 3rd, 1916 what he owed to her. (Brücke über den Strom, Volume 1, p. 123.)

I have written to you before that it is impossible to complete

your application for membership form. You never replied.

When I try to complete the application form, you repeatedly indicate that my email address is already held by another person.

I have held this email address for at least 20 years. I may have even contacted you in the past using my own, and only,email address: (jannmacmillan@googlemail.com) prior to changes in your recent presentation format.

I am disappointed that because of an error, I can no longer avail myself of reading reading your articles. I am a member of First Class.

Jacqueline ANN Whitehead (aka jacqueline ann macmillan)