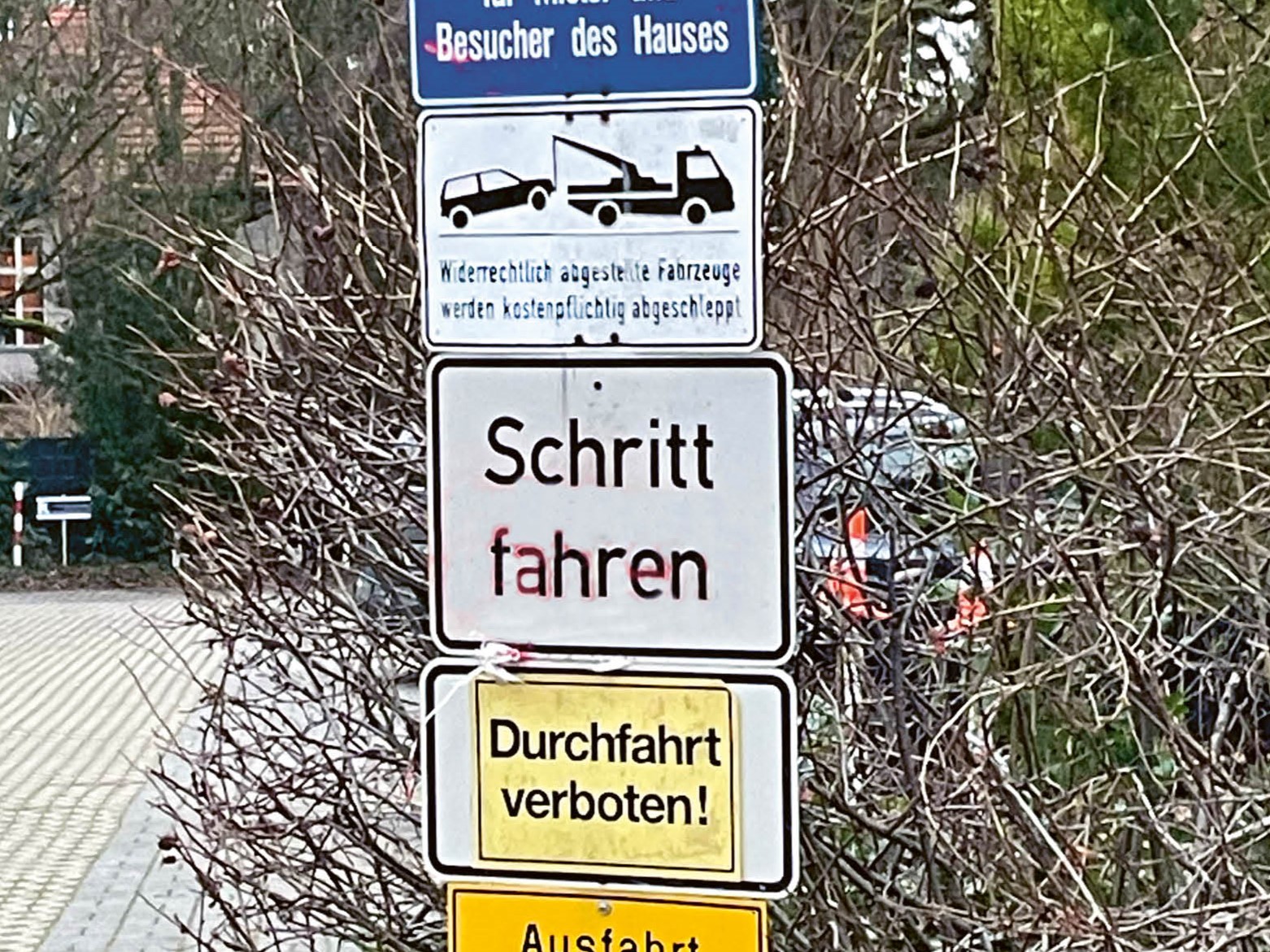

Five signs, one on top of the other, on a pole at the entrance to a parking lot in Berlin—a cacophony of prohibitions and regulations. It’s worth pausing to turn the quintet of signs into meditation material.

The soul wanders into the past of this property and its owners. Were bad experiences the cause of the fivefold “no,” or was it just excessive caution? How much anger inspired this signage? Whatever the case, the humor seems to have been lost.

I wish I had the bell that the anthroposophical clown Frieder Nögge told me about, nearly 40 years ago. He had a performance in the Foundation Stone Hall of the Goetheanum one evening. While inspecting the hall that afternoon, he experienced what he described as the weight of the hall’s atmosphere and thought, “No one will laugh here.” So he walked through all the rows, often crawling on all fours, and summoned humorous elemental beings with the sound of a bell, inviting them to the evening performance. It was a success, reported Nögge. I think I would like to bless this pillar of unfriendliness with such a bell.

For Myself

Then fate answers with a different kind of bell. On the opposite side of the street, an elderly man is carrying a litter grabber. With it, he deftly pokes at a pile of leaves and pulls out a pack of cigarettes, a beverage can, and other pieces of rubbish. In one elegant motion, everything he can grab goes into a plastic bag in a basket that he holds in his left hand.

More material for meditation. Even a cigarette butt and a bottle cap are not too small for him. The full plastic bag suggests that he has probably been on the street for an hour picking up litter. Like the signpost quintet, this story also has a past, but in this case, the eye-witness is here. So I ask: “Are you doing this for yourself?” A friendly face looks up from the ground and nods: “I’m doing it for myself!” I continue to look him in the eye in silence—an invitation to find out more. “If I come by here tomorrow and see that it’s clean and there’s nothing lying around, then I’ll be happy!” I ask how long he’s been doing this. Quite a few years, a bagful every day, he replies. He waves his hand, dismissing it.

It is an interesting counterpoint to the signpost opposite. There, a fivefold prohibition hurls a “no” at all who drive or walk past; here, a thousandfold self-directive gives a silent “yes” to the place, to all the carelessness of the litter strewn about, and to all those who have thrown something away here. There the threat, here the invitation, there the command, here the concern. So many contrasts in these two situations.

The collector collects for his own sake and, thus, for the sake of everyone. Can it be that Adam Smith’s classic economic metaphor of an “invisible hand” applies here? In his book Wealth of Nations, Smith (1723-1790) writes: “[b]y pursuing their own interest [an individual] frequently promotes that of the society more effectually than when they really intend to promote it.” The gap between rich and poor, documented capitalism and environmental destruction, reveals just how destructive this belief in self-interest is for our coexistence and nature. If, however, self-interest does not mean wanting to have, but rather striving and satisfaction, then things look different, then the happiness of the individual promotes the happiness of all.

Maturing in Silence

Secrecy seems to be of significance. The signpost segregates in a way that is visible to all—a sign wants to and should be seen; the rubbish collector unites, completely in secret. Yes, it’s the hiddenness that gives the good its dignity. I experienced this myself once—I felt it physically—in a little scene in the kitchen at home. It’s an everyday story: the dishwasher is still full of clean dishes, so I go ahead and empty it so that the other family members can put their dirty dishes in. Later, I hear: “Oh, how good, the children have emptied the dishwasher!” I can’t keep the truth to myself and blurt out who actually did the good. I pay for it immediately. It’s a sensation that seizes the whole body, and in an instant, the body becomes heavier—a previously unnoticed lightness is relinquished, as if invisible wings suddenly got tired. It brings to mind the observation that the act that one does without a witness is actually the free act. Rudolf Steiner takes meditation as an example of this. The decision to immerse oneself is free if no one knows about it because then it is only for one’s own sake. So, back to the litter collector: he probably had mighty wings on his back long before he was happy about the rubbish-free area the next day.

Translation Laura Liska

Photo Wolfgang Held

Mr. Held,

This is one of the most perfect and pithy pieces I have ever read here.

By attending to the mundane, you have opened us to the moral.

I especially appreciated:

“The signpost segregates in a way that is visible to all—a sign wants to and should be seen; the rubbish collector unites, completely in secret.”

pk

Dear Mr. Held,

I appreciate your view on this phenomenon of “acts in secret”.

Recently, I’ve noticed that upon perfoming an act on my own, without witness, I feel a presence within me, difficult to put into words, yet very enjoyable & at the same time, intriguing.

After reading your piece, I now have an insight into this experience.

My grateful thanks to you.

Tom McIntyre