Not many people who got to know Rudolf Steiner before the turn of the century followed him on the path to anthroposophy, but Felix Heinemann (1863–1935) was one who did.

Heinemann was born into a Hamburg merchant family and trained for a career as a publisher and bookseller. In 1896, together with Otto Neumann-Hofer (1857–1941), he took over the then-popular magazine Romanwelt [World of Novels] from the Cotta publishing house, which kept him fully occupied alongside his own publishing house, Vita. He later wrote in his memoirs about “Rudolf Steiner and the Magazin für Literatur [Magazine for Literature]”: “It is therefore understandable that I only listened with half an ear when one day Otto Neumann-Hofer suddenly asked me whether we wanted to take over the Magazin für Literatur.”1 Heinemann asked: “How much annual subsidy would I have to provide for this?” And, “If we take over the magazine, can you guarantee me that I personally won’t accrue any extra work, and promise me that the communication with the chief editor—by the way, who is that?—the editorial team, the authors, the printers, and the suppliers will be exclusively your responsibility?” Regarding the editorial chief, Otto Neumann-Hofer named “a ‘certain Dr. Rudolf Steiner.’ He is one of the most significant minds and one of the greatest experts among the new generation. His versatility is just as admirable as his thoroughness. The editorial leadership of the paper could remain entrusted to him without hesitation or restriction. Nor would I need to waste any time with him personally: he is a night worker, and I, a day person—we would hardly meet. I just don’t want to let my usual love of order have too much of a say because Dr. Steiner has his own views on this.”

Felix Heinemann was reassured by this information but later regretted: “One could have been so close to Rudolf Steiner, during his most important years of development, without having any understanding of his future world significance, without the time and the opportunity to become one of the first of his students to walk the path of the future among his followers! . . . A human age passed before I succeeded—and against what obstacles!—to find my way back to Rudolf Steiner.”

Worldly Hermit

At first, however, Neumann-Hofer was “unfortunately correct: Rudolf Steiner ‘cost me little time.’” But, “as the most decisive head of the publishing house,” Heinemann had to meet the editorial chief, at least once, in person. “One lunchtime (my early morning hours did not come into consideration for Rudolf Steiner), Otto Neumann-Hofer introduced him to me. . . . What an impression Rudolf Steiner made on me is clear from the fact that today, despite everything, I could still paint a picture of him from that time. To express it paradoxically, [the impression] was that of a worldly hermit. The most unforgettable thing was his eyes, unusually large, deep black, looking beyond the present into a distance, mysterious to us and, to a certain extent, painfully familiar to him, and more than the eyes, the gaze and the way of looking. Human beings speak so often of the eye and are not conscious of the difference between the eye and the gaze. The sharp, tired lines that outlined Steiner’s eyes in the last Dornach years were not yet present then. A great force streamed out from them, an enspirited willpower, already worked through to perfection at that time, but less easy to grasp through the tighter fabric of the younger head than in the manifold fine lines that we know from the carpentry workshop. . . . It was entirely self-evident that Rudolf Steiner lived and worked in accordance with his personality. He did not use the editorial offices and their equipment. He was a ‘home worker’ . . . and his manuscripts migrated in self-determined freedom from him to the printers.”

Odyssey to Switzerland

Not much is known about Felix Heinemann’s life; only a few documents on his path through life have been found. He married the Italian countess Raffaela Paulucci delle Roncole.2 The married couple lived in Berlin, where two children were born to them.3 Felix Heinemann joined a masonic lodge there in 1901; he was later appointed privy councillor. He supported the theater magazine Die Scene [The Scene] and financed the purchase of the bow and arrow collection of the ethnologist Leo Frobenius (1873–1938) for the Museum of Ethnology in Hamburg.

Later, Heinemann pursued a diplomatic and political career that saw him travel mainly, again and again, to Italy during the war years and afterward.4 All he himself ever wrote about this time was: “There may not be many private individuals who have looked so deeply and so painfully behind the scenes of these world events. After a veritable odyssey, I landed in Switzerland.”

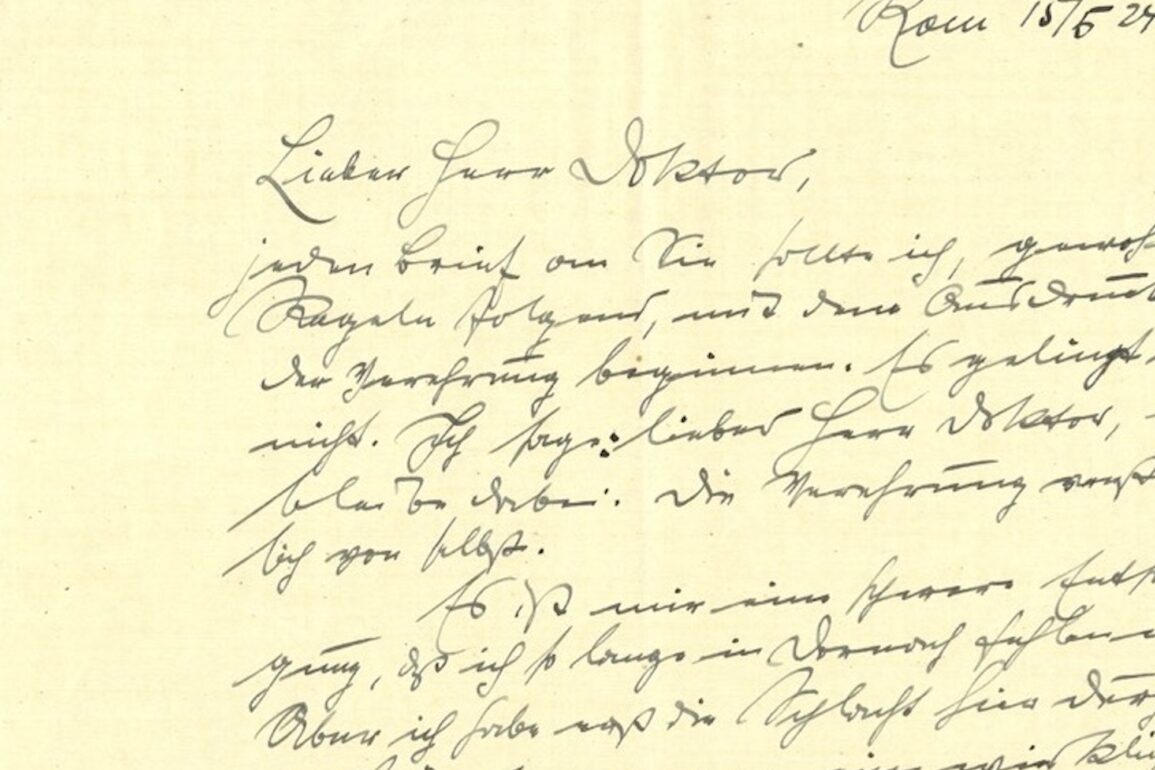

On March 12, 1917, still in Berlin, he once again wrote to Rudolf Steiner; on August 14, 1920, now living in Lucerne, he followed up: “My esteemed Herr Doctor, a very old acquaintance, who has long sought a reunion with you, and wrote, as well, but received no reply from the much-claimed and thus excused, is thus contacting you again today. With more success?”5 He now immersed himself “in Steiner’s writings more consistently than before and sought personal contact with him.”

As Equals

And yet, it was probably not until February 1924 that the requested conversation took place in Dornach: “No speech is able to convey the tone with which Rudolf Steiner received me. It seemed as if no time at all had elapsed between those old Berlin days and the present. I felt deep gratitude for the welcome—as equals—that he bestowed upon me, but I also accepted it as a gift and later often had the opportunity to observe that Rudolf Steiner was this heart-winning way, inherently, out of his innermost nature. Even though the Anthroposophical Society is expressly apolitical, this does not prevent the fact that Rudolf Steiner possessed the deepest insight into politics, its means and aims, and thought about this important area of life from the look-out of spiritual scientific knowledge.”

A stimulating exchange now evidently set in between the two, as is witnessed by the many letters from Felix Heinemann in 1924 and 1925 and the two letters in return.6 Felix Heinemann repeatedly visited Dornach and went to the lectures of Rudolf Steiner, and there were a few occasions for conversations.

In the meanwhile, he again had to manage difficult assignments in Rome. “It is a difficult abstinence for me that I have to be away from Dornach for so long. But, I have still to fight through this battle here, against a real hell. Perhaps I will know in eight days whether I will triumph or fall by the wayside.—My thoughts are with you and your work, morning to night.” 7

Between Dornach and the World

From September 1924, he seriously contemplated moving to Dornach in order to wholly and entirely stand at the disposal of Rudolf Steiner as a co-worker. What, on his side, Rudolf Steiner hoped for from him can be seen from his letter of December 31, 1924: “The whole structure of the Goetheanum administration must remain as it is now. For one can only do that for which one has people to do it. In particular, the financial administration must remain wholly in the same form, i.e., cared for by me alone. I couldn’t work any other way.—But that is precisely why I would greet it with pleasure if you, my dear Mr. Heinemann, could devote your circumspection and way of working to the cause. We need a lot of financial inflow in the near future in order to prevent the building from stalling. This can only be obtained if someone who is a man of the world mediates the relationship between anthroposophy and the world. Entirely matter-of-fact, reckoning on the understanding of human beings. That, you could do. But only if you are mainly in Dornach. Then, the widest possibility for further activities will result for you.”8

On February 15, 1925, Rudolf Steiner wrote that Heinemann’s letter prompted so many questions in him “that it is impossible for me at this moment to write to you what I have to write to you. My health is still wholly labile, and I have to pick out the moments when I may risk doing more than what the technical side of building and the most needful from the administration currently demand of me. . . . So, don’t be cross with me if I don’t reply to your letters until the next few days. It will certainly happen then. . . .—With the warmest regards, also rooted in old memories, wholly yours, Rudolf Steiner.” Felix Heinemann assured him on March 12: “As far as I have become and still remain a master of circumstance, I always hold myself ready to attempt the work that you wish me to do and for which you should believe me capable.” And from Heinemann’s last letter, on March 25, 1925, we learn that Günther Wachsmuth had written to him that Rudolf Steiner wanted to speak to him, “but would have to wait and see” when he could “arrange it.” It never came to pass.

A Possible Delay

When one knows how few people Rudolf Steiner received on his sickbed, one can surmise how important contact with Felix Heinemann was to him. And one asks themselves: What did he want to talk to him about? Clearly, he was hoping for important impulses from this man, who brought with him great world experience and the will to commit himself wholly to the cause of anthroposophy. Felix Heinemann intimates the basic tenor of the conversations that took place: “And since Rudolf Steiner was convinced or knew that practical and theoretical experience had matured me to the comprehension of his views, he thus opened to me comprehensive insights, filled with deep concern, the basic tone of which came to its final notes in the fear of a possible delay, about which may perhaps, at some time, be discussed elsewhere.”9

On March 1, 1927, Felix Heinemann moved to Arlesheim, where he died on May 23, 1935.

Translation Joshua Kelberman

Footnotes

- All the following quotations (unless otherwise noted) from Felix Heinemann-Paolucci, “Rudolf Steiner und das Magazin für Literatur,” in Das Goetheanum (1928): 283 ff.

- Harry Graf Kessler, who met the Heinemann couple, on March 28, 1918, on the train from Bern to Lucerne, characterized her as a “nice, amusing Italian.” Harry Graf Kessler, Das Tagebuch [The diary] 1880–1937 (Stuttgart: Cotta, 2004, p. 337). Curiously, Raffaela Paulucci delle Roncole was the daughter of Agnes von Dönniges, who was the sister of the famous Helene von Schewitsch. Rudolf Steiner met Helene von Schewitsch in Munich in 1903. See Martina Maria Sam, “‘Dieses Leben hatte eine tiefe Tragik’ [This life had a deep tragedy]. Helene von Schewitsch,” Das Goetheanum, no. 24 (June 16, 2022).

- Birth certificates were only able to be located for these two children (Margaretha, in 1903, and Kurt Gernot, in 1905), but it is possible that more children were born.

- See the journal La Vita italiana: rassegna di politica interna, estera, coloniale e di emigrazione [The Italian Life: review of domestic, foreign, colonial, and emigration policy], vol. 1917.

- All the letters quoted here are found in the Rudolf Steiner Archive [in Dornach, Switzerland], which also holds the copyright to them.

- Felix Heinemann wrote about a “number of his letters,” which were his “greatest treasure.” Presumably, these were more than the two surviving letters.

- Unfortunately, the particular letters from Heinemann to which Rudolf Steiner refers in his reply letters are clearly missing.

- Felix Heinemann probably did not do this; nothing is known about it, and he has not commented on it elsewhere.

- See footnote 1.