On the Background to the “Questionnaire” of 1892

One of the circles of friends that Rudolf Steiner belonged to in Weimar was formed around the newly married couple Hans and Grete Olden. “They gathered a social circle around them that wanted to live in the ‘present,’ in contrast to everyone who saw the center of spiritual life as the continuation of the past at the Goethe Archive and Goethe Society. I was accepted into this circle, and I think back with great sympathy upon everything I experienced there. No matter how strongly our ideas in the archive were stiffened by experiencing the ‘philological method,’ they had to become free and fluid whenever we came to the Olden’s house, where everyone was interested in and set upon the idea that a new way of thinking must gain ground in humanity; but also where everyone sensed the pain of old cultural prejudices, with a soulful inwardness, and thought of future ideals.”1

Hans Olden (1859–1932) had initially been an actor and was now active as an “author of light-hearted theater pieces,” but had “an open heart for the highest interests present in the spiritual life of the time.”2 His (second) wife, Grete (1860–1933), had also been active in the field of theater. With her first husband, Paul von Schönthan, and his brother Franz, she produced the famous comedy Der Raub der Sabinerinnen [The Rape of the Sabine Women] in 1883, which continued to be successful for several decades. She was also the favorite niece of the influential journalist, writer, and theater director Paul Lindau, who, among other things, had also written popular plays.

While still Grete von Schönthan, she started a keepsake album in January 1889 with the title Erkenne Dich selbst! Gedenkalbum zur Charakteristik der Freunde und Freundinnen [Know Yourself! A Commemorative Album of Friends’ Characters]. A template album of the kind was published by Friedrich Kirchner, who wrote that he had become acquainted with this parlor game in England. It was intended to serve for the study of human beings, but not in a false way: “Lavater studied physiognomy; Gall studied skulls; others sought to unravel human beings . . . from handwriting, still others from photography. Young people keep albums in which they immortalize their . . . youthful friendships through mostly affectionately tasteless, sentimental, and untrue poetry.” Now, however, a new path to understand the human being stood open. “If your friends . . . answer the following twenty-five questions, they have thereby made a general confession that no inquisitor could elicit more comprehensively and truthfully with screws and pliers. So prying and, at the same time, so skillful are the questions that bombard your friends that—without suspecting anything and even disregarding any reluctance—they will reveal their feelings, thoughts, and idiosyncrasies, thus painting an accurate picture of themselves. To some, this or that question may seem intrusive or superfluous. Let him not answer it, but, mind you, only when he has realized through careful reflection that it really deserves such censure.”3

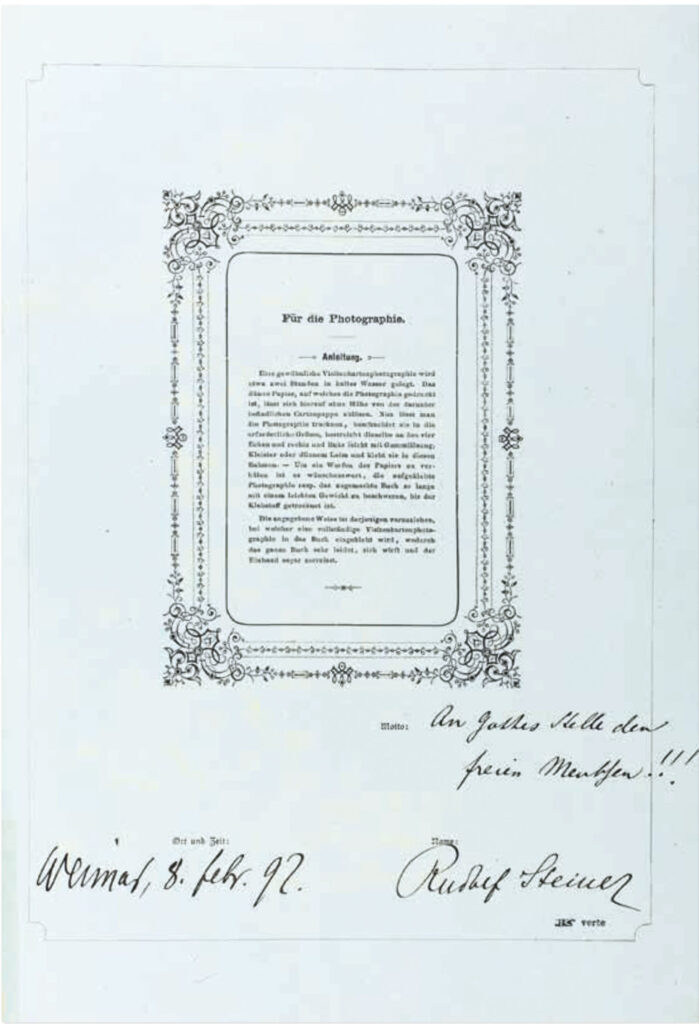

Almost all the entries in the album date from the beginning of 1889. In the ten entries from that time, immortalized next to the Gerike members of Greta’s birth family, were also her then-husband, playwright Paul von Schönthan (1859–1905), and his colleague, Ludwig Fulda (1862–1939). Evidently, Grete Olden did not unpack the book again until February 1892 in Weimar. First, on February 7, Rudolf Steiner’s colleague at the archive, Eduard von der Hellen, and his wife, Martha, filled out questionnaires. The couple belonged to Olden’s inner circle.4 And finally, on February 8, came Rudolf Steiner’s turn! That remained the last entry, and the book was probably forgotten about again. There are no questionnaires filled in by other members of the circle, such as Gabriele Reuter or Julius Wahle.

The character of the circle, as Gabriele Reuter describes it below, forms an interesting background against which Rudolf Steiner’s answers must partly be seen. “We were all individualists of the purest water . . . . We surely all honestly believed that we were working on the utmost personal development within ourselves, while we simply shared in the developments of life most typical of the time. . . . We had all read Stirner. He had laid the foundations for us with his theoretical logic, his brazen, relentlessly clear language, and the sober coldness of his thought processes, which in the end only led to an ashen nothingness. So then, Friedrich Nietzsche became our god. Our spirits revolved around him, like planets around the sun. . . . We all had different natures in our circle of friends—rich or versatile or even devious—the subtle magician probably had a different effect on each of us. But since none of us lacked an imagination, we each created our own adored and solemnly revered Friedrich Nietzsche.”5

This circle, who all so revered Nietzsche, traveled to Naumburg on May 26, 1894, at the invitation of the new Nietzsche publisher, Fritz Koegel. “And when he would pause for a moment,” remembers Gabriele Reuter, “we heard . . . from the next room, a muffled murmuring and muttering, like the sounds of a captive animal . . . . That was the sick Nietzsche, sitting in there and knowing nothing more of his work, before whom we bowed, trembling.”6

Nietzsche was, thus, the sun around whom revolved the spirits of the Olden circle—and this was also reflected to a certain extent in Rudolf Steiner’s answers to some of the questions. For the beginning of 1892 was not yet the time of his great enthusiasm for Nietzsche. This would not fully unfold until about two years later.

So, on February 8, 1892, Rudolf Steiner filled out the “questionnaire.” Even if the whole thing was fun and games, when we look at his answers, they seem to speak more of his yearnings at the time than of his previous convictions. In a way, the questionnaire bears witness to the fact that he had embarked on a path to descend from his purely idealistic heights and turn to earthly reality. 7

“Your favorite quality in a person? ‘Energy’ Which profession do you think is the best? ‘Any job where you can burst with energy.’ When would you like to have lived? ‘In times, when there is something to do.’ Your idea of unhappiness? ‘Knowing nothing to do.’ Which historical characters do you dislike? ‘The weak.’”

At the time, Rudolf Steiner was anything but “full of energy.” In fact, he was struggling with malaise throughout the year 1892. Also, with his favorite heroes of history and favorite artists comes a valuation of this urge to be full of force, which hardly corresponded to him physically.

“Favorite heroes in history? ‘Attila, Napoleon I, Caesar.’ Favorite heroines in history? ‘Catherine of Russia.’ Favorite characters in poetry? ‘Prometheus.’ Your favorite composers? ‘Beethoven.’ Your favorite painters and sculptors? ‘Rauch, M. Angelo.’”

The fact that the classicist sculptor Christian Daniel Rauch (1777–1857) is mentioned in the same breath as Michelangelo is surprising, as he is not mentioned anywhere else by Rudolf Steiner. But the fact that his favorite pastime coincides with his idea of happiness is probably not just a joke. Both times, he answers “musing and loving” [Sinnen und Minnen], no doubt inspired by the collection of poems of the same name by Robert Hamerling, which Pauline Specht had given him for his 26th birthday. Musing [Sinnen] is thinking that is connected to the inner human being, not just an activity of the head; with the addition of “Minnen” [loving]—which means “to love” [lieben], but has the same etymological origin as mind, manas, Mensch [human being], that is, loving connected with the spirit—then we almost feel reminded of what Rudolf Steiner later described as “thinking with the heart,” when thinking and feeling are connected in a new and conscious way.8

In some things, he doesn’t show an interest; with others, one doesn’t really know how serious he is:

“Where do you want to live? ‘It’s all the same to me.’ Your main character trait? ‘I don’t know.’ Your favorite thing about a woman? ‘Beauty.’ Your favorite color and flower? ‘Violet. Autumn crocus.’ Your insuperable dislike? ‘Pedantry and a sense of order.’ What are you afraid of? ‘Punctuality.’ Favorite food and drink? ‘Frankfurter sausages and cognac. Black coffee.’”

The last may have been true at the time. If we are to believe tradition, Frankfurt sausages were probably one of the few meals he was able to prepare himself at the time. And the fact that he abhorred pedantry, orderliness, and punctuality may have had something to do with the fact that these qualities were constantly demanded by the archive and its publishers; perhaps, he was thinking of the archive director Suphan. The fact that he mentions the unusual name “Radegunde” when asked about his favorite names is probably related to the memory of the woman he once loved.9 With regard to men’s names, he remarks succinctly, “That, women may decide.”

Mentioning Nietzsche twice is certainly connected with the mood of the Olden circle outlined above:

“Who would you like to be if not you? ‘Friedrich Nietzsche before the madness.’ Your favorite writers? ‘Nietzsche, Hartmann, Hegel.’”

So, among his favorite writers, he also mentions Nietzsche—not Goethe! This is to be understood against the background that, in 1891, Rudolf Steiner tried to “free” himself from Goethe in a certain respect.10

The answer to the following two questions may well have come from the bottom of his heart:

“Which mistakes would you forgive most easily? ‘All, once I understood them.'” Your temperament? ‘Changeability.’”

The first is reminiscent of the words attributed to Madame de Staël: “To understand all is to forgive all.” There are various testimonies to the fact that Rudolf Steiner had a special gift, even at a young age, of being able, at times, to empathize with the innermost feelings of other people. And “changeability”—this is not inconstancy, but rather the ability to change and yet remain true to oneself. Indeed, he, himself, was in just such a process of transformation, which he clearly felt.

His “motto” (which actually should have been placed under a photograph of him, but it was never inserted) corresponded to his phase of life at the time—the move towards a Philosophy of Freedom: “In place of God, the free human being!!!”11 In Notebook 492 from that time, something very similar is written: “History is, in truth, the development of the human race towards freedom. First, the spirit feels dependent on God, [then] works its way to freedom, and knows itself. In place of belief in God, I believe in the free human being / Dr. Rud. Steiner.”12

Even if the questionnaire was only a game and, as stated above, not all the answers are to be taken literally, it is informative to see that, on some points, Rudolf Steiner gave himself a kind of program for the coming years.

Translation Joshua Kelberman

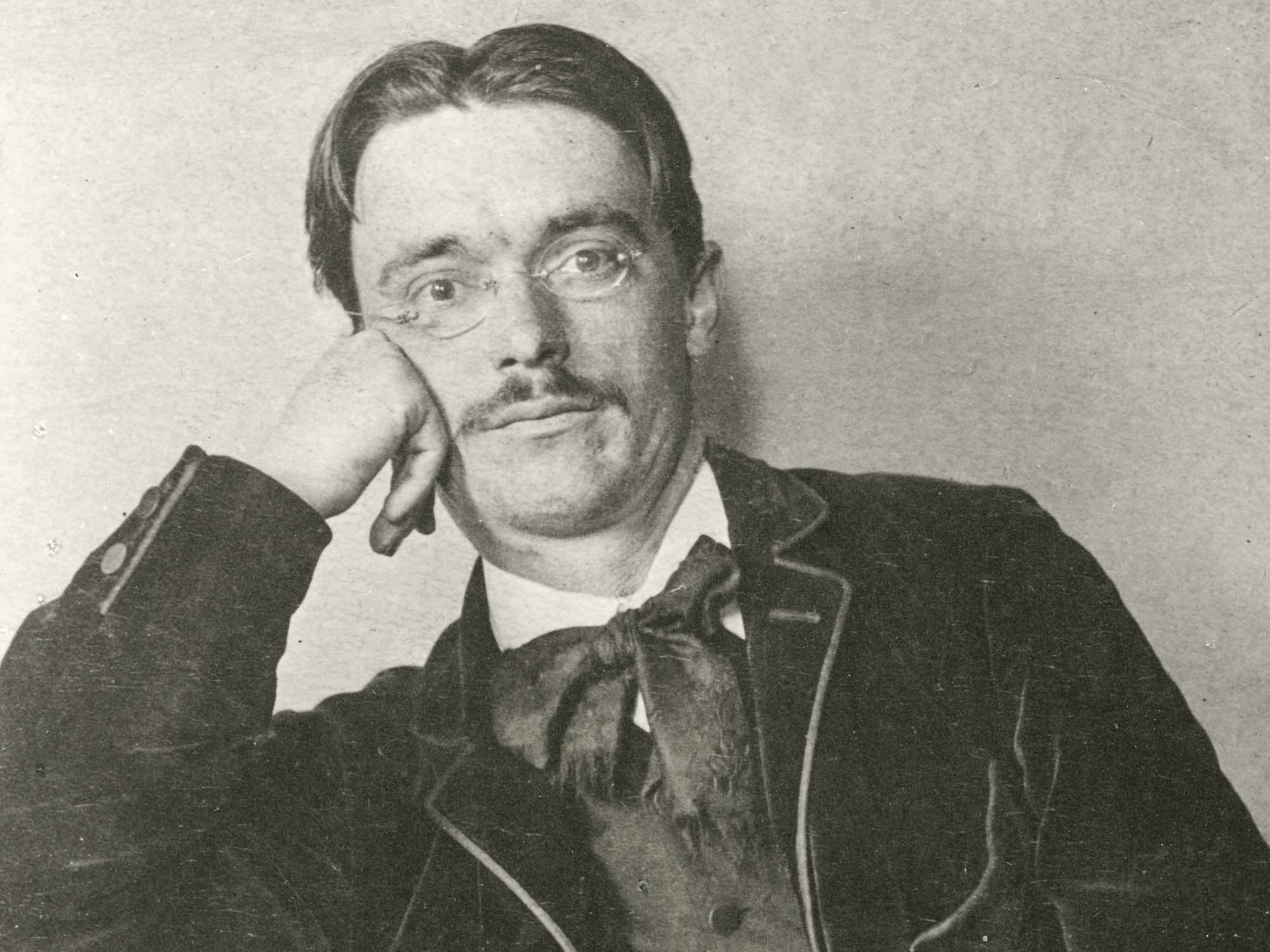

Title image Rudolf Steiner around 1891

Footnotes

- Rudolf Steiner, Autobiography: Chapters in the Course of My Life, 1861–1907, CW 28 (SteinerBooks, 2006), ch. 36.

- Ibid.

- Friedrich Kirchner, Erkenne Dich selbst: Gedenkalbum zur Charakteristik der Freunde und Freundinnen [Know Yourself: A Commemorative Album of Friends’ Characters] (Weber, no date).

- Rudolf Steiner shares his esteem for the couple in his Autobiography; see note 1, ch. 46.

- Gabriele Reuter, Vom Kinde zum Menschen: Die Geschichte meiner Jugend [From Child to Adult: The History of my Youth] (Hofenberg, 2017).

- Ibid.

- In his Autobiography (see note 1), Rudolf Steiner explains how this path came to a certain conclusion in his last year in Weimar, how his interest in the sensory world strongly intensified, and how he now undertook spiritual cognition with his will, while previously he had been guided by the ideal.

- Rudolf Steiner, Macrocosm and Microcosm: The Greater and the Lesser World. Questions Concerning the Soul, Life and the Spirit, CW 119 (Rudolf Steiner Press, 2021), lecture in Vienna on March 29, 1910.

- See chapter 5 concerning the Fehr Family in Martina Maria Sam, Rudolf Steiner: Die Wiener Jahre. [The Vienna Years] (Dornach, 2021).

- details in my forthcoming volume Rudolf Steiner. Die Weimarer Jahre [The Weimar Years].

- With this, it is also fitting that he called Prometheus his favorite character in poetry.

- Rudolf Steiner, Wahrspruchworte [Words of True Verse], GA 40, 10. edn. (Dornach, 2019).