It was an over-flowing carpentry workshop: there had been so much demand for the acting course planned for September 1924 that Rudolf Steiner felt the need to open the doors to all 700 interested people—professionals and amateurs alike. A true image of theater art?

Speech formation concerns us all. The dimension of the word is one of the central concerns of anthroposophy. As Rudolf Steiner formulated (in CW 280), “Only when one learns to hear can one learn to speak.”1 Hearing requires a different kind of attention than seeing. It brings us into our “‘I’ of the periphery”; it creates space for what has not yet arrived; it is deeply connected with our sphere of will. The oracles in Delphi were “heard.” The language of the gods in Samothrace, according to Rudolf Steiner, was heard in the smoke rising from the Cabeirian clay pots—a reading, an inner hearing.

Not only do we need ingenious, inspirational artists on stage, we also need an artistically interested and, in the best case, an artistically trained audience. This is the only way to establish the “cake mold and cake” relationship between stage and audience, the only way to turn the interrelationship between audience space and stage space into an event space, something reminiscent of the double cupola principle of the First Goetheanum (which, in 1924, still lay in ruins). This idea does not detract from the fundamental concern that art should touch us directly, have a direct effect, and set the forces slumbering within us into motion. The questions always arise anew: What sources do we draw on as directors and actors in a production? From which sources do we develop our instrument, allowing something unprecedented to happen on stage, something that can follow from the ancient Mystery art in order to become the new Mystery of today?

Speech formation is a concept that already existed in German-speaking countries (for example, in Austria) before Marie von Sivers and Rudolf Steiner gave the first speech formation courses in 1919 for lecturers within the Threefolding movement and for prospective Waldorf teachers at the first Waldorf School in Stuttgart. Marie von Sivers had studied the art of recitation and declamation in St. Petersburg, Paris, [and Berlin] before she met Rudolf Steiner and, through him, anthroposophy. However, she realized that what she had learned didn’t resonate. In 1912, Rudolf Steiner began working with Lory Maier-Smits following a conversation with her mother concerning her vocational training, and together, Marie and Rudolf Steiner developed the speech required for this new art of eurythmy: the art of speech formation.

Then, in 1924, actors approached Rudolf Steiner with a request to receive indications out of anthroposophy for their profession as well. As a result, a professional course was announced for September 1924: “Speech Formation and Dramatic Art.”2 As already mentioned, on account of their insistence, not only the professionals but all those interested were admitted. The art of theater as a harmony of speech formation, drama, and eurythmy began—now, it is a legacy of Marie and Rudolf Steiner. In nineteen lectures, within which Marie Steiner-von Sivers recited, Rudolf Steiner developed aspects of the humanistic foundations of speaking, speaking styles, training through the five disciplines of Greek gymnastics, and the true gestures to be developed from them. He showed that all speech is based on a gesture (the six shades or variations of speech formation). The lectures also dealt with pronouncing vowels and consonants, dreams, moods of speech sounds and their progression within a drama, directing, and even with the esotericism of the theater artist.

Everything Lies In Speech

What especially appealed to me during my personal studies? As a seventh grader at the Mannheim Waldorf School [Freien Waldorfschule Mannheim] with my instructor Dora Gutbrod (who had participated in the 1924 “Dramatic Course” at the age of 19), and later in my studies (with Ursula Ostermai, Erika Pommerenke, Caroline Wispler, Karin Hege, Mirjam Hege, and Sighilt von Heynitz), I experienced something that fascinated me, something that took me far beyond my previous experiences of listening: my love of speech. Seemingly everyday situations opened up a previously unimagined realm of experience for me when listening to these masters. For example, lines about bolting a door shut in Conrad Ferdinand Meyer’s “The Feet in the Fire” [Die Füße im Feuer] or in Hilde Domin’s “Only a Rose for Support” [Nur eine Rose als Stütze] became a magical moment for me as I listened:

Firmly, he bolts the door [Fest riegelt er die Tür]

C. F. Meyer

I want to feel the sand under my little hooves and hear the clack of the bolt that closes the stable door in the evening

Hilde Domin

[Ich will den Sand unter den kleinen Hufen spüren und das Klicken des Riegels hören, der die Stalltür am Abend schließt]

“Think upon the what, think more upon the how,” says Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s Homunculus in Faust, part 2 [line 6992]. Yes, I was able to experience this. Through the “how” of the reciters, I experienced the determined, longing-for-security closure of the door by the courier who was tormented by fear of death; it happened in speaking and listening, all at once. An inner world also opened up to me through the “how” of the clack of the bolt on the stable door, the longing for security. Rilke calls this an “inner world-space” [Weltinnenraum]3—this event space that “opens in astonishment and moves everything, lets me be there,” and at the same time gives me the gift that “I will then feel myself, complete and whole,”4 as Rudolf Steiner wrote in a verse for a teacher of ancient languages. These are seemingly paradoxical examples: in the sensible world, something is closed (the bolt of the door) and, through speaking and thus through the sensible experience of hearing, perceiving language, etc., spaces open up—spaces of experience, new dimensions. Yes, everything lies in speech!

Breathing in a New Space

During my speech formation studies (1989–1993), I enjoyed attending the lyric and epic readings that actors and actresses from Theater Basel gave in the foyer, starting at 11 o’clock in the evening, after the usual theater program. I was touched by how their love and dedication to the texts became palpable, how their soul expressed itself freely through the texts they themselves chose. Often, more happened here for me than in the theater performances themselves. The readings by Hans-Dieter Jendreyko and his productions also had this attraction for me. I was similarly electrified by Peter Brook’s productions—I didn’t want to miss a single performance in Basel, Bern, or elsewhere. And the production of The Dybbuk, written by Salomon An-ski, with Miriam Goldschmidt and Urs Bihler, had a magical effect on me. It made me hold my breath and yet kept me breathing, but in a way previously unknown to me, in a new space.

Today, I realize that these artistic experiences opened something up in me that I also know during meditation, something that has become more and more apparent as my life continues—it is a kind of “being touched by something higher” that, in some way, can be sensed. I can acquire the instrument, the permeability, by way of something that I’ve brought with me (sometimes called “giftedness” or talent), as well as through long practice and perseverance, in order for it to become a “habit,”5 a “second human being,”6, as Rudolf Steiner called it. Only then can I act with inspiration, indeed, with intuition; only then can the other side play its part of giving grace.

My journey with the lecture cycle Speech Formation and Dramatic Art began during my studies. We speech formation students freely decided to meet one evening per week to study the Dramatic Course together. Whether it was about Rudolf Steiner’s suggestions for directing or about training to become a speech formation actor, everything was discussed and debated in conversation, even heatedly, and noted in the margins of the book for easy retrieval. I was fascinated, for example, to learn how different the effect is when I step on stage from one side or the other, and what this means for the audience. The connection with the differing receptivity of our left and right eyes led me to experiment, and I still use opportunities to involve unbiased people in this research today. It’s obvious that my path has found its focus in speech formation.

The fact that speech formation and dramatic art are “one” art is something I can experience now more than ever with the new course that opened this year: Amwort Theater Art [Bühnenkunst amwort] is a long-awaited close collaboration with colleagues in acting and eurythmy. With the professional colloquium, which took place at the Goetheanum on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the lecture cycle, and four full days of theater performances in July 2024, we want to work out collaborative impulses and research proposals with which we can ring in the new century of our art.

More Section for the Performing Arts Newsletter, no. 80, “Dramatic Course Centenary” (Easter 2024)

Translation Joshua Kelberman

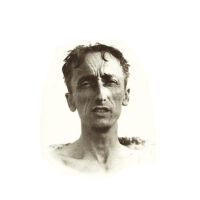

Image An Enemy of the People by Herik Ibsen, 2007. Stockmann: Torsten Blanke, Hovstad: Matthias Hink, Aslaksen: Thomas Autenrieth. Photo: Charlotte Fischer.

Footnotes

- Rudolf Steiner, Creative Speech: The Nature of Speech Formation, CW 280 (London: Rudolf Steiner Press, 1999, repr.), p. 34.

- Rudolf Steiner, Speech and Drama, CW 282 (Spring Valley, New York: Anthroposophic Press, 1986, repr.). German title Sprachgestaltung und Dramatische Kunst [Speech Formation and Dramatic Art], lectures in Dornach on Apr. 10, 1921 and Sep. 5–23, 1924.

- Rainer Maria Rilke, Sämtliche Werke [Collected Works], 6 vols. (Frankfurt: Insel, 1956), p. 92.

- Rudolf Steiner, Wahrspruchworte [True Verse Words], CW 40 (Dornach: Rudolf Steiner Verlag, 1981); see Rudolf Steiner, The Genius of Language, CW 299 (Great Barrington, MA: Anthroposophic Press, 1995), p. 7.

- See footnote 1, “From a Note Book, 5 August 1922,” p. 100.

- Rudolf Steiner, Sprachgestaltung und Dramatische Kunst [Speech Formation and Dramatic Art], CW 282 (Dornach: Rudolf Steiner Verlag, 1981) p. 348, lecture of Sep. 21, 1924; cf. Rudolf Steiner, Speech and Drama, p. 372; The phrase “second human being” [zweiten Menschen] is translated as “whole being” in English.